Inside State’s First 24/7 Opioid Treatment Center

Community Medical Services in West Allis saves lives, confronts stigma.

In December 2012, John Koch, was 24 years old and living on the streets of Chicago. He had just been released from prison, having served a 3½ year sentence –“my second adult prison sentence,” he told Wisconsin Examiner. The young man had struggled with heroin addiction since he was 15 years old.

That was just seven years ago. Now 30 years old, Koch proudly serves as director of community engagement at Community Medical Services (CMS), a medication-assisted treatment center for opioid use disorder that now has 28 clinics in nine states. CMS offers treatments including methadone, suboxone, and vivitrol coupled with psychological counseling. “We’re not just addressing your addiction,” he tells Wisconsin Examiner. “We like to address the whole person.”

In April 2019, CMS became the Badger State’s first ever 24-hour Opioid Treatment Program (OTP), with a center located in West Allis. Since it first opened its doors in Arizona in 1983, thousands of people have found treatment with CMS. Recovery is possible, and sometimes can open doors to unexpected places, Koch says.

“I never thought I’d work in the treatment field,” says Koch. “I was like, a construction worker most of my life. I didn’t think this was going to be my thing.” His personal road to recovery, along which Koch became CMS’s first peer support specialist, began with a traffic stop in southwest Chicago, “right off of heroin highway,” he recalls.

John Koch guides Wisconsin Examiner on a tour throughout the CMS facility. Photo by Isiah Holmes/Wisconsin Examiner.

It was March 2013 and, despite still dealing with the fallout of his last prison sentence, Koch found himself pulling out of a McDonald’s parking lot holding “a bunch of heroin,” he recounts. “I’m with a guy who’s had warrants for three years.” As if that wasn’t enough, “I’m in this ridiculous car, and I forgot to turn my lights on.” A police cruiser started following the 1996 Toyota Camry, which was made up of a multi-colored patchwork of junkyard parts. “When I pull down the street I see the cherries pop behind me,” says Koch, referring to the police cruiser’s red and blue rail lights.

Believe it or not, Koch “felt a huge sigh of relief” as he pulled over into an alley. Estranged from his family, he was living on the street. “I’m having to do crazy stuff to obtain my drugs at the time,” Koch confessed. When the older white officer approached him, Koch didn’t have I.D. and didn’t know if the car was even his. “I still to this day don’t know how I got that car,” he told Wisconsin Examiner.

In that context, jail sounded like the best option, and he prepared to re-enter the system after less than a month of freedom. “I don’t hide the drugs, I don’t hide the needles,” he tells, “I’m like, ‘I’m cool with it. Lets go.’” After a brief dialogue, the officer handed Koch a blank warning slip with a treatment center’s contact information on the back. “He looks me in the face and says, ‘Kid it looks like you need some help. Call this number, let them know that I sent you. Get out of here, the highway’s that way.”

The next day Koch entered treatment. It wouldn’t be long before he met CMS CEO Nick Stavros, who was moved by the trials Koch endured. “I’m very blessed to be working with these people that gave me an opportunity,” he says.

Spreading The Message

Now several years into recovery, Koch has re-purposed his life and is dedicating himself to breaking down barriers to recovery for users. “Anyone can walk in at any time of day,” reports Koch. “We have some form of coverage 24 hours a day.” When people struggling with addiction walk through CMS’s doors, their needs are evaluated at the front desk.

“To start in our program,” he explains, “some people come in here and are still high. They’re maybe impaired, or they’re sick.” Doctors and counselors are available for new and returning clients around the clock at CMS. Those returning for further treatment can check in on an ipad-like screen near the front desk. The device sorts people as they wait for their medications. “Our average wait time for the whole company, not just here, is under five minutes,” Koch says.

Particular attention at CMS is dedicated to streamlining service for their patients. “We’ve had major universities come through and break down how we can best do our operations,” says Koch.

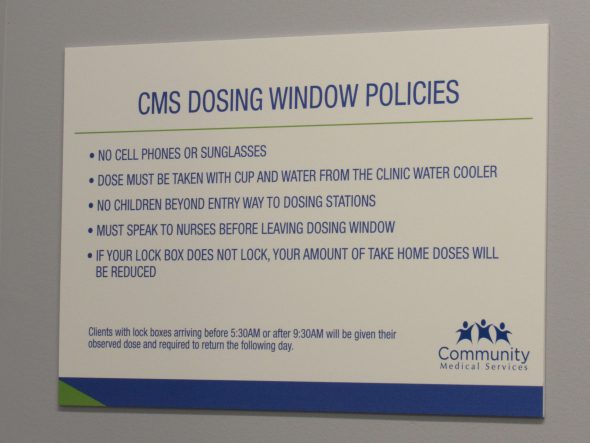

“Our clients have to be here six, seven days a week. And then they get privilege levels every 90 days, as long as they’re following the rules. We’re highly regulated,” Koch says. The Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), Wisconsin Department of Health, Milwaukee County, and a crediting agency are just a few layers of oversight at CMS. Each therapy office is also required to be attached to a sound-canceling device, ensuring conversations between counselors and patients remain private.

Therapy rooms are wired to sound-cancelling devices on the floor. Photo by Isiah Holmes/Wisconsin Examiner.

Talk therapy occurs in sound-proofed offices, including rooms with various calming themes. Koch says the so-called “bird room” is most popular. Patients, however, can also choose the seashell room, or a room with no theme at all. The rooms are designed to provide personal conversations in which the patient feels listened to, and valued. “If you were to look at another methadone program, you’re not going to see it look like this,” he says proudly.

A variety of payment options is also available for patients, whether through Medicaid or the County. “If you don’t have Medicaid, we have a program where we foot the bill for you until you get back on your feet,” explains Koch. “We don’t want payment to be a deterrence to treatment. If you’re not in treatment, you’ll probably die. And we don’t want that for anybody.”

Koch also pushed back against assumptions about medication-assisted treatment. “People think we hand out pills and all this stuff,” he told Wisconsin Examiner. In the case of methadone, “we give a liquid, it’s put into a little cup. You get a glass of water, and you drink water with the methadone. It tastes like crap, I used to be on it.” Patients also are given suboxone, “the nurse will watch you on it and watch it dissolve in your mouth,” explains Koch.

The important part isn’t the medication, it’s working through trauma

Vivitrol shots are also provided through CMS, though with less frequency. According to Koch, less than 1% of the people who’ve sought treatment at the clinic get on vivitrol. “Some people think of it as a miracle shot,” explains Koch. “But the big part about this isn’t the medication. It’s actually the counseling, and the doctor’s visits, and peer support, so you can learn to work through your trauma.

”Everyone’s recovery is individualized. “Some people will be on it for six months, some people will be on it for 20 years,” he explains. “And that’s OK.”

Koch points out that over 23 million people nationally identify as being in recovery, but only 3 million are part of a 12-step program. It’s important to look at all aspects of a treatment program, including the risks and benefits. “A five day detox costs as much as a whole year of our treatment.” According to the National Institute on Drug Addiction, 40-60% of patients struggling with addiction relapse.”

Despite the benefits, medication-assisted treatment as a practice, sadly, is subjected to a variety of unproductive stigma. “The main stigmas you hear is, ‘replacing one drug with another.’ Another is, ‘it’s free dope or why do they get methadone when I have to pay for my medication. Another thing is, ‘You’re not clean. Or you’re not in ‘recovery.’” Despite these negative assumptions Koch says, “everybody’s recovery is different.”

Dr. Drew Palin MD, one of the friendly faces patients encounter at CMS, says these ideas cut deeper than people realize. “The stigma that society has on Opioid Use Disorder is the major obstacle to us dealing with it effectively,” he explains. To combat the idea that addiction is a choice, Dr. Palin emphasizes the numerous biological factors at play.

“For 30 to 50% of the people who use it,” he says, “the first time they use it, they’re almost hooked. Because they’re so genetically predisposed to it when they take it, they suddenly feel normal. They feel human.” Eventually, “they don’t get high anymore and they’re just using it to not get sick. Which is a sad commentary.”

“The saddest thing about it, in my mind, is that it’s happening to more and more young people,” he adds.Explaining that the 21 to25-year-old age group has seen the highest increase in overdoses, Dr. Palin says, “That’s when you’re creating your life, your career.” Even younger users struggling with addiction “don’t have any energy and interest in that,” he says. “So for the rest of their lives, they’re behind the eight ball.”

Trauma plays a bigger role in addiction than any failings in character or will-power on the part of the addicts. According to Dr. Palin, some 60% of women in a methadone program have experienced physical or sexual abuse. “Why wouldn’t you take a drug?” he asks. “It’s a rational thing to do when you’re trying to get away from that kind of pain.” The real problem, Dr. Palin says, is “that society has defined it [addiction] as a moral failure.” It’s not. “That’s a real society failure.”

Stigma is a barrier to treatment

Government bureaucracy isn’t always the biggest hurdle for alternative treatment options. “We tried to open in Milwaukee and got ran off,” Koch recounts with some regret. CMS initially tried to open a clinic on Capital Drive, near a neighborhood with lots of houses. While local alders supported CMS, some community members pushed back.

“It was a lot of NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard) kind of stuff,” say Koch. “You know, ‘We want drug treatment, just not here. Why don’t you open up over here, or over here?” He says, “they [the community] thought we were bringing drug addicts to their neighborhood. Which actually, the heat map showed that was one of the most overdosed areas in Milwaukee.”

Rumors also circulated on social media that “people might try to attack,” Koch recalls. This forced the library which hosted the public forum to request extra security. No incidents occurred, but the message was loud and clear.

Ultimately, CMS found a location at 2814 S. 84th street in West Allis, next to a Payless ShoeSource. “There was a lot of community support and they were experiencing a lot of overdoses out here,” says Koch.

Community Medical Services has expanded as demand has increased for flexible treatment centers. In 2017, more than 70,000 people died of a drug overdose in the United States, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Wisconsin’s rate of opioid overdose deaths for that year was 16.9 per 100,000 persons, higher than the national average of 14.6. Addiction and death do not discriminate. “It’s something that can affect anyone,” says Koch. Nearly one in three people nationally knows someone who has struggled with addiction to opioids and opiates.

At the end of the day, Koch says, the common denominator is providing love and compassion for hurting people. “I prescribe methadone,” says Dr. Palin, “but what I really try to do is give them some respect by treating them as normal human beings who have a tough problem. And they need to be encouraged and honored for trying to deal with that. It’s not easy.”

Koch pleads with cities and communities, “We have to break down the stigma. It’s vital to people staying alive.”

Reprinted with permission of Wisconsin Examiner.

More about the Opioid Crisis

- Attorney General Kaul Announces Consent Judgment with Kroger Over Opioid Crisis - Wisconsin Department of Justice - Mar 21st, 2025

- Baldwin Votes to Strengthen Penalties, Step Up Enforcement Around Deadly Fentanyl - U.S. Sen. Tammy Baldwin - Mar 17th, 2025

- Wisconsin Communities Get Millions From Opioid Settlement as Deaths Decline - Evan Casey - Mar 1st, 2025

- MKE County: County Creates Easy Public Access To Overdose Data - Graham Kilmer - Feb 18th, 2025

- Milwaukee County Executive David Crowley and the Office of Emergency Management Launch New Overdose Dashboard - County Executive David Crowley - Feb 18th, 2025

- Fitzgerald Advances Legislation to Fight Opioid Epidemic - U.S. Rep. Scott Fitzgerald - Feb 6th, 2025

- Milwaukee Is Losing a Generation of Black Men To Drug Crisis - Edgar Mendez and Devin Blake - Jan 31st, 2025

- Milwaukee County’s Overdose Deaths Declined For Second Straight Year - Evan Casey - Jan 27th, 2025

- MKE County: United Community Center Awarded Drug Company Money For Addiction Treatment - Graham Kilmer - Jan 12th, 2025

- DHS Provides Update on Distribution of Latest Opioid Settlement Funds - Wisconsin Department of Health Services - Jan 9th, 2025

Read more about Opioid Crisis here