The Future of Wisconsin Gerrymandering

An inexplicable U.S. Supreme Court decision leaves door open for GOP mischief.

![How to Steal an election. Image by Steven Nass (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.](https://urbanmilwaukee.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/How_to_Steal_an_Election_-_Gerrymanderingj.jpg)

How to Steal an election. Image by Steven Nass (Own work) (CC BY-SA 4.0), via Wikimedia Commons.

In writing for the court’s five to four majority, Chief Justice John Roberts made it clear that both “districting plans at issue here are highly partisan, by any measure.” Here is a taste of his description of the North Carolina gerrymander:

The Republican legislators leading the redistricting effort instructed their mapmaker to use political data to draw a map that would produce a congressional delegation of ten Republicans and three Democrats. … As one of the two Republicans chairing the redistricting committee stated, “I think electing Republicans is better than electing Democrats. So I drew this map to help foster what I think is better for the country.” … He further explained that the map was drawn with the aim of electing ten Republicans and three Democrats because he did “not believe it [would be] possible to draw a map with 11 Republicans and 2 Democrats.”

Roberts is no kinder to the work of Maryland Democrats:

The Maryland Legislature—dominated by Democrats—undertook to redraw the lines of that State’s eight congressional districts. … The Governor later testified that his aim was to “use the redistricting process to change the overall composition of Maryland’s congressional delegation to 7 Democrats and 1 Republican by flipping” one district. … To achieve the required equal population among districts, only about 10,000 residents needed to be removed from that district.

It’s worth noting that this stance is very different from that taken by the Wisconsin Republicans. They continued to claim that their gerrymander resulted from the state’s geography.

Roberts dismisses one of the chief arguments of the gerrymander defenders, noting that they:

… suggest that, through the Elections Clause, the Framers set aside electoral issues such as the one before us as questions that only Congress can resolve. … We do not agree. In two areas—one-person, one-vote and racial gerrymandering—our cases have held that there is a role for the courts with respect to at least some issues that could arise from a State’s drawing of congressional districts.

Thus, the courts have already crossed that Rubicon.

Taken along with the earlier Wisconsin case, Gill v. Whitford, the Rucho decision represents a kind of bait and switch. In Whitford, “we held that a plaintiff asserting a partisan gerrymandering claim based on a theory of vote dilution must establish standing by showing he lives in an allegedly ‘cracked’ or ‘packed’ district.” And so lawyers representing Wisconsin’s Democrats did just than, only to see the standing question largely ignored in Rucho.

Why, then, does Roberts conclude the courts should not get involved with partisan gerrymanders? His decision revolves around an exaggerated view of the difficulties involved.

The “central problem” is not determining whether a jurisdiction has engaged in partisan gerrymandering. It is “determining when political gerrymandering has gone too far.”

But both racial gerrymandering and setting equally sized districts also require judgment calls.

… the fact that such gerrymandering is “incompatible with democratic principles,” does not mean that the solution lies with the federal judiciary … partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts.

In her dissent Justice Kagan skewers Roberts’ argument:

After dutifully reciting each case’s facts, the majority leaves them forever behind, instead immersing itself in everything that could conceivably go amiss if courts became involved.

Joined by Justices Ginsburg, Breyer, and Sotomayor, Kagan continues:

For the first time ever, this Court refuses to remedy a constitutional violation because it thinks the task beyond judicial capabilities.

And not just any constitutional violation. The partisan gerrymanders in these cases deprived citizens of the most fundamental of their constitutional rights: the rights to participate equally in the political process, to join with others to advance political beliefs, and to choose their political representatives. In so doing, the partisan gerrymanders here debased and dishonored our democracy, turning upside-down the core American idea that all governmental power derives from the people. These gerrymanders enabled politicians to entrench themselves in office as against voters’ preferences.

So the only way to understand the majority’s opinion is as follows: In the face of grievous harm to democratic governance and flagrant infringements on individuals’ rights—in the face of escalating partisan manipulation whose compatibility with this Nation’s values and law no one defends—the majority declines to provide any remedy.

Roberts argues that others, either Congress or others, may have a remedy. For example,

The first bill introduced in the 116th Congress would require States to create 15-member independent commissions to draw congressional districts and would establish certain redistricting criteria, including protection for communities of interest, and ban partisan gerrymandering.

Unmentioned is that so long as Republicans control the US Senate, this bill will go nowhere.

Likewise, state efforts to set up independent commissions face serious obstacles, including from Roberts himself. He joined a dissent that would have blocked a commission adopted by a majority of Arizona voters.

Furthermore, many states–like Wisconsin–lack any provision for a referendum that would allow voters to establish a commission over the opposition of legislators who benefit from gerrymandering. Even where voters have that ability, efforts to take redistricting out of politics face legal challenges from those benefiting from gerrymandering. In Michigan, for instance, a federal lawsuit challenges the nonpartisan redistricting commission established by a voter-approved amendment to the state constitution. If successful, this challenge could affect other states, such as California, with similar commissions.

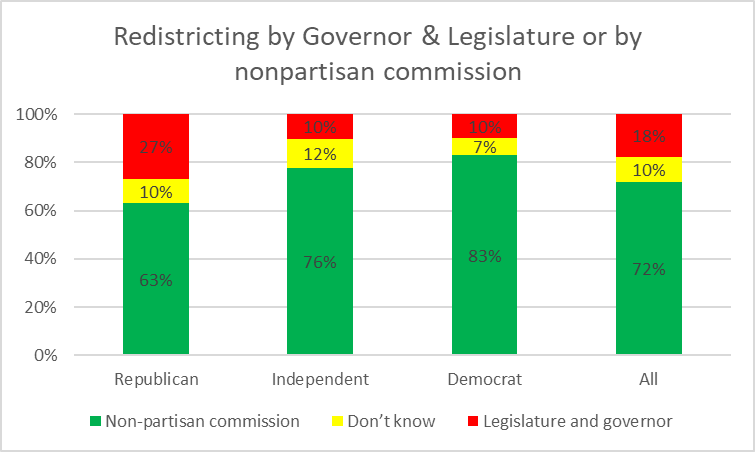

Opponents of gerrymandering should expect little relief from the federal courts, at least with the present justices. Probably the best route is to exploit the bipartisan unpopularity of gerrymandering. For example, this January’s Marquette poll asked whether responsibility for redrawing maps of legislative districts should rest with the state legislature and governor or a non-partisan commission.

On this issue, at least, Republican voters are far more pro-democracy than the current class of Republican politicians. The unpopularity of gerrymandering helps explain why pro-gerrymandering politicians like former governor Scott Walker accuse gerrymander opponents of gerrymandering. Consider the following statement posted on the National Republican Redistricting Trust website:

Democrats, led by Barack Obama and Eric Holder, will stop at nothing to gerrymander Democrats into permanent majorities. They believe the courts, not the voters, should pick the winners and losers in our elections and that the ultra-liberal representatives they put into office will pass their radical left-wing agenda.

Governor Scott Walker knows how important it is that we fight back before all our pro-growth reforms are wiped away. Join Governor Walker and the NRRT to fight back against the Democrats’ nationwide power grab.

The Democrats are laser-focused on reversing Republican gains in redistricting control and imposing their anti-democratic extreme gerrymandering schemes across the country.

Given that the Republican party has recently evolved into the gerrymandering party, it is easy to forget that politicians from both parties both practiced it. Roberts quotes Democratic Congressman Steny Hoyer, the US House majority leader, describing himself as a “serial gerrymanderer.”

The unpopularity of gerrymandering among voters may help explain the fate of the recent suggestion that the legislature could redistrict Wisconsin by joint resolution, thus cutting out Governor Evers, allowing the Wisconsin gerrymander to extend over the coming decade. To do so would require reversing a 1964 decision in State Ex Rel. Reynolds v. Zimmerman, in which the Wisconsin Supreme Court declared that:

The apportionment of both houses of the legislature is vital to the functioning of our government. There is just as much reason for considering it as one of the basic functions that requires full legislative treatment as any other major phase of government activity which admittedly requires joint action by the legislature and the governor.

The quick denial by Republicans of any intention to bypass the governor may reflect the unpopularity of gerrymandering. Yet a comment by Rick Esenberg that a joint resolution is “the only way out of … an assured impasse” suggests that Republicans may bring the idea back. After all, impasses are usually considered bad.

The present trend in which Republicans defend gerrymandering and Democrats are the party of nonpartisan districting, may hold dangers for both the anti-gerrymandering cause and for the Democratic party at the national level. It could lead to a situation where the partisan split in blue states reflects the actual support among voters, but in which Republicans win extra seats in red states because of gerrymandering.

More about the Gerrymandering of Legislative Districts

- Without Gerrymander, Democrats Flip 14 Legislative Seats - Jack Kelly, Hallie Claflin and Matthew DeFour - Nov 8th, 2024

- Op Ed: Democrats Optimistic About New Voting Maps - Ruth Conniff - Feb 27th, 2024

- The State of Politics: Parties Seek New Candidates in New Districts - Steven Walters - Feb 26th, 2024

- Rep. Myers Issues Statement Regarding Fair Legislative Maps - State Rep. LaKeshia Myers - Feb 19th, 2024

- Statement on Legislative Maps Being Signed into Law - Wisconsin Assembly Speaker Robin Vos - Feb 19th, 2024

- Pocan Reacts to Newly Signed Wisconsin Legislative Maps - U.S. Rep. Mark Pocan - Feb 19th, 2024

- Evers Signs Legislative Maps Into Law, Ending Court Fight - Rich Kremer - Feb 19th, 2024

- Senator Hesselbein Statement: After More than a Decade of Political Gerrymanders, Fair Maps are Signed into Law in Wisconsin - State Senate Democratic Leader Dianne Hesselbein - Feb 19th, 2024

- Wisconsin Democrats on Enactment of New Legislative Maps - Democratic Party of Wisconsin - Feb 19th, 2024

- Governor Evers Signs New Legislative Maps to Replace Unconstitutional GOP Maps - A Better Wisconsin Together - Feb 19th, 2024

Read more about Gerrymandering of Legislative Districts here

Data Wonk

-

The Imperial Legislature Is Shot Down

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

Counting the Lies By Trump

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Did Politics Affect Covid Deaths?

Jun 26th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jun 26th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

“Inexplicable”?

From a party that outright stole a Supreme Court seat by denying, in advance, any and all nominees from the duly elected Democratic president? From a party, several of whose representatives including our own Glenn Grothman, that its motivation in seeking “voter ID” laws and other restrictions on voting is entirely to remain in power?

It’s entirely explicable.