The Gerrymander Wars March On

Wisconsin Republicans strategy is to support Maryland gerrymander that hurts GOP voters.

Two gerrymandering lawsuits are set for argument before the US Supreme Court on March 26. While neither directly involves the Wisconsin gerrymander, there are strong Wisconsin strains running through each of them. The court’s decisions in these cases is likely to heavily influence the outcome in the Wisconsin challenge. The court’s earlier non-decision in the Wisconsin case will heavily influence those who will argue these two cases. Finally, many of the characters who played parts in the Wisconsin case reappear in the new cases.

One of the cases, Rucho v Common Cause, involves a challenge to a Republican gerrymander of all North Carolina seats in the US House of Representatives. A three-judge panel of federal judges ruled against the gerrymander. That decision was appealed to the Supreme Court.

In Maryland, only one US House seat, the 6th, was challenged. In that case, Lamone v Benisek, a Democratic gerrymander successfully converted that district from Republican to Democratic, turning the whole Maryland delegation into Democrats.

Rucho and Lamone are state officials, charged in their official capacity with defending their state’s gerrymander. Common Cause is among several organizations that challenged the North Carolina redistricting.

Benisek is one of several Republican voters living in Maryland’s 6th district. As he explains:

State officials responsible for Maryland’s 2011 congressional redistricting targeted plaintiffs and other like-minded voters for disfavored treatment because of their past support for Republican candidates for public office. These officials’ aims were achieved: the weight of Republicans’ votes in Maryland’s Sixth Congressional District was severely diluted and Republicans’ associational activities were significantly disrupted as a result of the gerrymander.

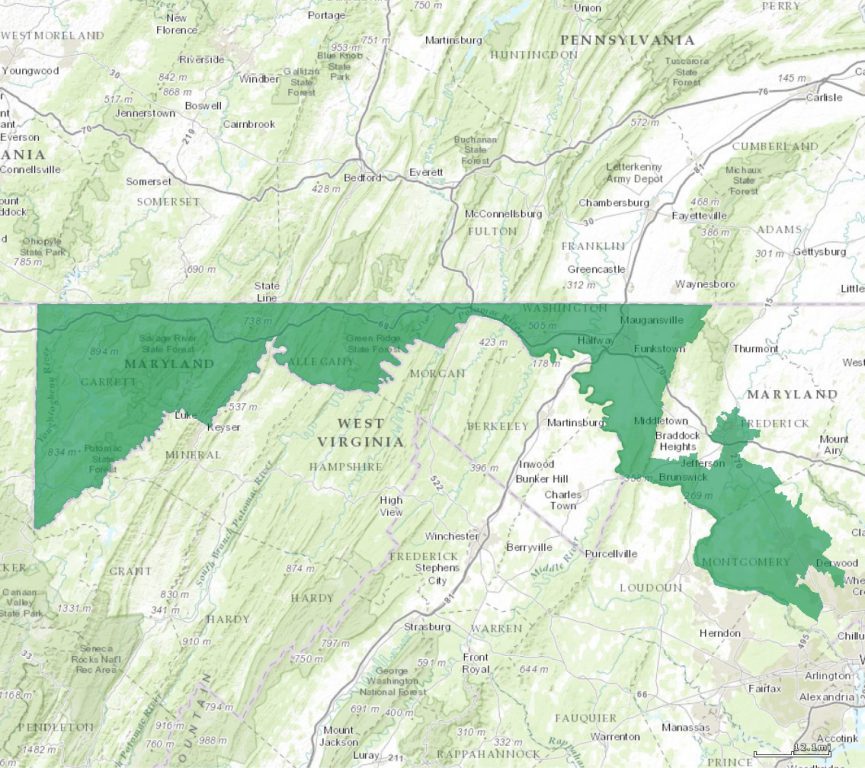

The map below shows the gerrymandered 6th district. Most of the district is western Maryland, squeezed between the Potomac River on the south and the Mason-Dixon line on the north that separates Maryland from Pennsylvania. Switching the district from red to blue consisted of adding the mostly Democratic appendage on the southeast which extended the district into the Washington metro area. The mostly Republican voters to the north of that were added to a safely Democratic district.

This is hardly the ugliest or most bizarrely creative Maryland Congressional district. A look at a map of Maryland congressional districts is proof that Democrats are no slouches at gerrymandering when they set their minds to it. For example, consider the 3rd District:

The 3rd District is represented by John Sarbanes, who is listed as the principal author of HR 1, the “For the People Act of 2019,” which, among other provisions, contains the “Redistricting Reform Act of 2019,” which would require that Congressional redistricting be conducted by independent redistricting commissions. HR 1 was passed by the Democratically controlled US House and sent to the Senate, where Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has promised to kill it.

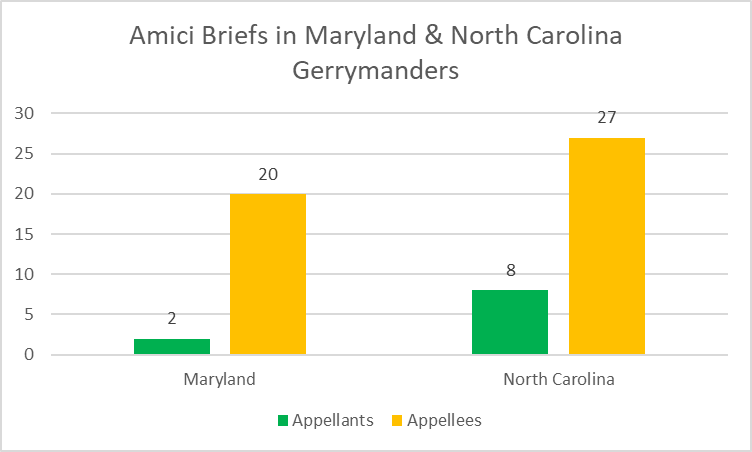

Further evidence for the increasing toxicity of partisan gerrymandering is contained in the distribution of “amici” briefs, briefs from outside groups and individuals who hope to influence the court’s decision. Here are links to the North Carolina briefs and the Maryland briefs.

The amici briefs state at the top whether they support one of the two parties to the case. The party appealing the lower court’s decision against gerrymandering are called “appellants,” while those arguing that the Supreme Court uphold the lower court are “appellees.” In other words, amici briefs in favor of appellants support gerrymanders; those for appellees oppose the gerrymander.

As the next chart shows, the anti-gerrymander position is far more popular than the pro-gerrymander side. Almost everyone — 47 different individuals or organizations — wants to beat the gerrymander to death, compared to just 10 defending it. The amici briefs come not only from the usual constitutional lawyers, but include mathematicians and experts in big data aiming to reassure the justices that measuring gerrymanders is very doable. Historians discuss the concern the founders had about officials entrenching themselves. Also represented are legislators (mostly retired in the case of Republicans) warning that gerrymanders increase polarization.

By contrast, the pro-gerrymander amici mostly come from people with a stake in the outcome: legislators who might lose their job or Republican operatives. In the Maryland case, there are only two amici supporting the gerrymander. One is from the six-district Democratic Congressman who nonetheless assures the court he is no supporter of gerrymanders as evidenced by his sponsorship of the For the People Act.

The other comes from the Wisconsin State Senate and Assembly whose Republican leadership shows no reluctance to throw the Maryland 6th District Republicans under the bus. Except for its label, their brief supporting the Maryland gerrymander is Identical to that for the North Carolina gerrymander.

In their brief, our Wisconsin legislators make several arguments. The first is that the apparent “cracking” and “packing” is the innocent result of demographics—it is the fault of Democrats for clustering in cities. The success of this argument assumes an extraordinary gullibility by the justices. Whatever the effect of demographic patterns, the authors of redistricting in all three states went well beyond what was needed to meet the traditional standards for redistricting to assure continued domination for their side.

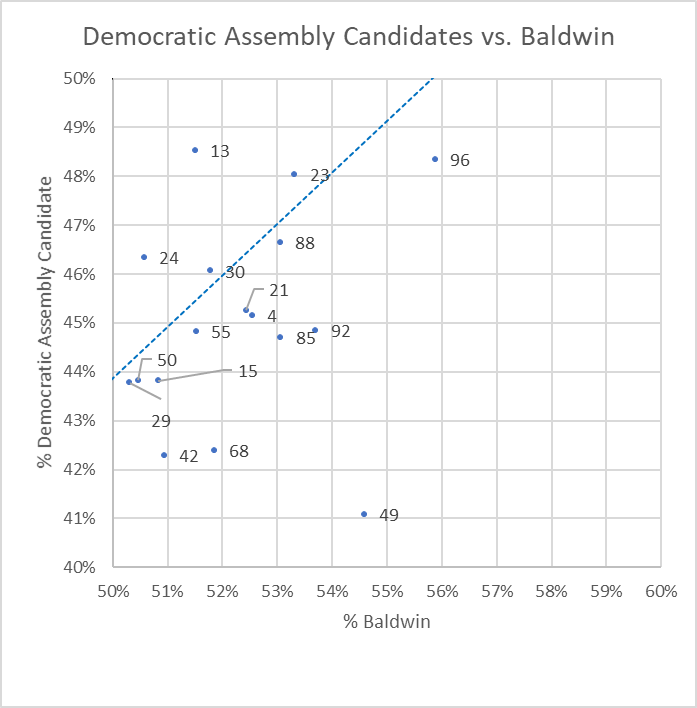

Our Wisconsin legislators also point to the 2018 Wisconsin election results to argue that gerrymandering does not matter because Republican voters may become Democrats and vice versa: “Partisanship is not an immutable characteristic.” In support of this argument, they point to the districts, shown below, that both Democratic U.S. Senator Tammy Baldwin and the Assembly Republican candidate won.

But this pattern is not new — in both 2008 and 2012 Obama ran well ahead of most Democratic Assembly candidates — and proves nothing. Designers of guaranteed Republican congressional, senate and assembly seats can go about their business with little worry that gerrymandered districts will become suddenly unstuck.

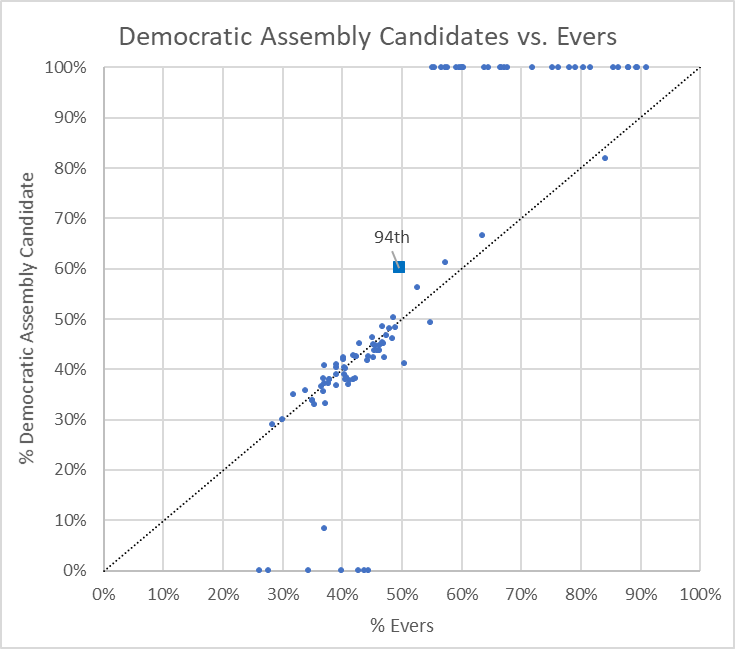

The race for Wisconsin’s governor was a much better predictor of district outcomes than was the race for US senate. As the next graph shows, only one assembly district, the 94th, that Evers lost was won by the Democratic Assembly candidate.

Another state connection to national gerrymandering battle is Misha Tseytlin, Wisconsin’s former Solicitor General, who was hired by Republican members of the North Carolina congressional delegation to write an amicus brief in support of the gerrymander. His main interest is challenging the claim that the federal courts are the “only institution in the United States capable of solving the” problem of too much politics in the redistricting process.

Tseytlin summarizes some of the efforts of 19th century congresses to limit state efforts to gain partisan advantage through redistricting, noting that most were allowed to lapse in the 20th century. I found his summary of 250 years of efforts to stifle gerrymandering profoundly depressing. After all those attempts, we are still confronted by politicians scheming to entrench themselves in power.

Tseytlin asserts that “Congress and the states have the authority to decide the proper role that political considerations should play in the redistricting process.” The issue, however, is not whether Congress and state legislatures have the authority to solve the threat to democracy posed by gerrymandering. They plainly do. The relevant question is whether they can be trusted to overcome the conflict of interest they are faced with. Wisconsin’s legislature proves that partisan advantage often trumps a commitment to democracy.

More about the Gerrymandering of Legislative Districts

- Without Gerrymander, Democrats Flip 14 Legislative Seats - Jack Kelly, Hallie Claflin and Matthew DeFour - Nov 8th, 2024

- Op Ed: Democrats Optimistic About New Voting Maps - Ruth Conniff - Feb 27th, 2024

- The State of Politics: Parties Seek New Candidates in New Districts - Steven Walters - Feb 26th, 2024

- Rep. Myers Issues Statement Regarding Fair Legislative Maps - State Rep. LaKeshia Myers - Feb 19th, 2024

- Statement on Legislative Maps Being Signed into Law - Wisconsin Assembly Speaker Robin Vos - Feb 19th, 2024

- Pocan Reacts to Newly Signed Wisconsin Legislative Maps - U.S. Rep. Mark Pocan - Feb 19th, 2024

- Evers Signs Legislative Maps Into Law, Ending Court Fight - Rich Kremer - Feb 19th, 2024

- Senator Hesselbein Statement: After More than a Decade of Political Gerrymanders, Fair Maps are Signed into Law in Wisconsin - State Senate Democratic Leader Dianne Hesselbein - Feb 19th, 2024

- Wisconsin Democrats on Enactment of New Legislative Maps - Democratic Party of Wisconsin - Feb 19th, 2024

- Governor Evers Signs New Legislative Maps to Replace Unconstitutional GOP Maps - A Better Wisconsin Together - Feb 19th, 2024

Read more about Gerrymandering of Legislative Districts here

Data Wonk

-

Why Absentee Ballot Drop Boxes Are Now Legal

Jul 17th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 17th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Imperial Legislature Is Shot Down

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

Counting the Lies By Trump

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson