Do Defense Lawyers Overlook Childhood Trauma?

Too many fail to investigate mitigating evidence of such trauma, says national expert in MU Law School speech.

Defense attorneys are failing their clients if they neglect to understand, investigate, and present evidence of childhood trauma in criminal cases, says a legal and neuroscience expert.

Deborah W. Denno, a professor and founding director of the Neuroscience and Law Center at Fordham University School of Law, spoke last week at Marquette University Law School.

Denno obtained her law degree and a Ph.D. in sociology from the University of Pennsylvania and has taught at Fordham Law, the London School of Economics, Columbia Law School and Princeton University.

She visited Marquette to give the annual Barrock Lecture on Criminal Law, presenting her research and conclusions about the use of childhood-trauma evidence in adult criminal cases.

Denno studied criminal cases reported nationwide, investigating how defense attorneys introduced and how courts assessed the mitigating and aggravating impacts of neuroscience evidence. Neuroscience is the branch of life science focusing on the brain and nervous system.

Denno researched written court decisions reported in the online legal databases Westlaw and Lexis from 1992 to 2012. She found 800 criminal cases involving neuroscience evidence. She reviewed those and then narrowed her focus to the 266 cases involving childhood trauma.

Denno acknowledged that written opinions reported in Westlaw and Lexis are predominantly from appellate courts, so her research involved mostly appellate court decisions. Further, almost all of the 266 cases she reviewed in depth were homicide cases, and most involved the death penalty.

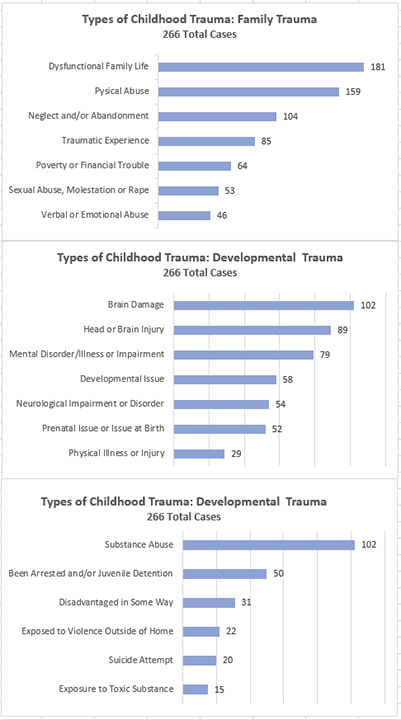

She looked particularly at the types of childhood trauma defendants had suffered, conditions caused by or related to the trauma, how evidence of the trauma or conditions was presented to courts, and the courts’ responses. From the 266 cases she identified 20 types of trauma, which she grouped as either family, developmental, or external trauma. On average, each defendant in the 266 cases had suffered five different types.

Conditions caused by or related to childhood trauma included, among other things, physical disabilities, post-traumatic stress disorder, emotional and behavioral issues and mental illness.

According to Denno, evidence of childhood trauma was predominantly introduced as a mitigating circumstance at sentencing; 246 of the 266 cases included such mitigation evidence. In 161 cases such evidence was introduced to support a claim of ineffective assistance of counsel. But in only 33 cases did defense counsel present childhood trauma or a resulting condition in defending against the crime. (Denno counted cases multiple times if the evidence was used in different ways.) Courts accepted at least some of the trauma evidence in 246 of the 266 cases.

In 57 of the 266 cases, the court held that defense counsel had provided ineffective assistance of counsel — a disproportionately high rate, in Denno’s view, when compared to the rare success of such arguments in general. The most common reason for failure of an ineffective-assistance claim was that the attorney’s decision not to present the evidence was based on reasonable trial strategy.

Based on her research, Denno opined that defense attorneys are failing their clients by neglecting to investigate the mitigating evidence of childhood trauma; failing to work with the defendant, his or her family, and experts to fully develop or present evidence of childhood trauma; failing to understand the long-term effects of childhood trauma on future behavior; poorly strategizing or presenting evidence; and failing to draw connections between past trauma and the crimes committed.

Denno recognized the challenges attorneys faced when presenting such evidence in the cases she studied. Crimes were heinous. Claims of childhood trauma were deemed vague, depended on unreliable memories, or involved conflicting views of the defendant’s history. And, importantly, such evidence was often viewed by defense counsel and courts as a double-edged sword — the effects of childhood trauma could be considered grounds for a harsher sentence as much as for mitigation.

However, in Denno’s view, such evidence should be pursued and considered more often. She advocates for use of childhood trauma evidence in a broader array of cases than death penalty cases.

Defense attorneys need to educate themselves on the long-term effects of trauma, she said. In addition, Denno said, a defense attorney should thoroughly investigate a defendant’s background and family history; communicate to the defendant the importance of such evidence; draw a connection between childhood trauma evidence and criminal behavior; and better communicate to the judge and jury how childhood trauma has affected the defendant as an adult.

Childhood trauma evidence is most compelling when counsel shows a connection between the trauma and the criminal behavior, she said.

During a question-and-answer session, former Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice Janine Geske noted that defendants may be hesitant to have counsel raise childhood trauma at sentencing when that may malign the very family members in the courtroom to support the defendant.

Denno acknowledged that concern and the complexity of counsel’s considerations in such instances, especially if family members are set to speak on the defendant’s behalf. Denno suggested that counsel could raise issues of childhood trauma when family members are not present.

When asked by another audience member for her thoughts on why some people exposed to childhood trauma commit crimes while others do not, Denno said each person responds to trauma differently; a particular child will have particular responses.

Denno teaches a seminar on law and neuroscience at Fordham and brings in neuroscience experts to talk with her students. She suggests similar instruction at other law schools and recommends that practicing attorneys find neuroscience experts who can educate them on childhood trauma.

Court Watch

-

No Unemployment Benefits For Worker Making Homophobic Remarks

May 17th, 2022 by Gretchen Schuldt

May 17th, 2022 by Gretchen Schuldt

-

Appeals Court Upholds Injunction Against Abortion Protester

Mar 13th, 2022 by Gretchen Schuldt

Mar 13th, 2022 by Gretchen Schuldt

-

80% of State’s Judicial Races Uncontested

Feb 20th, 2022 by Gretchen Schuldt

Feb 20th, 2022 by Gretchen Schuldt