Let Us Now Praise America’s Workers

Photographer David Plowden poignantly captures a disappearing era of blue collar work and workers.

Dessie Higgenbottom Proprietress Dessie’s Bar & Grill, Pocahontas, VA 1974. Photo courtesy of the Grohmann Museum.

Photographer David Plowden’s subjects are deckhands, ship captains, railroad engineers, ranchers, factory workers, and restaurant and clothing store owners with one thing in common: pride in their chosen occupation. His black-and-white photographs capture the heart of blue collar America over nearly half a century

Plowden’s “Portraits of Work” exhibition which features dozens of photographs taken at locations across the United States, is now on display at the Milwaukee School of Engineering’s Grohmann Museum.

“This was a great opportunity for us to take another look at his work over the past five or six decades,” said James R. Kieselburg II, museum director.

He noted that “Portraits of Work,” which will be donated to the Grohmann by Plowden when the exhibition ends, is a fitting addition to the museum, the only one in the United States which specializes in artwork portraying human labor, occupations and production.

In “Portraits of Work,” the artist changes the focus, giving progress and industry a human face.

Plowden used a 2 ¼” by 2 ¼” Rolleiflex camera to shoot the exhibition pictures. The camera’s square lens gives the photographs a neatly framed appearance.

A handful of prints are displayed next to various photos, each with a narrative on the back. Bat Nelson, a 90-year-old barber in Alta Vista, Kansas, uses much of the same equipment he has since his shop opened. He sits on an antique barber chair, hands crossed in front of him and head held high.

In other photos a Chinese cook on a steamship leans on a peer railing, smiling, a cigar between his teeth. A young man who has just enlisted in the U.S. Army sits on a coach in a Nebraska bus station. A seasoned ship captain poses in his dress uniform.

The exhibit can also be read as a travel essay. Some of the stories are lighthearted and uplifting; others are somber. It’s clear the photographer is charmed, intrigued and moved by his subjects.

Although many of Plowden’s photos depict elderly laborers who lived through the Great Depression, others are children and young adults (although these subjects would be middle-aged today). The majority of his subjects are white men, although some photographs of women and minority workers and business owners are displayed. For example, Dessie Higgenbottom, owner of Dessie’s Bar and Grill in Pocahontas, Virginia, sits in a wooden booth, smiling, a twinkle in her eye and an empty Miller High Life bottle on the table.

The subjects of these photos share a familiarity with and a willingness to work physically demanding and potentially dangerous jobs, even if they’d rather be elsewhere.

The younger workers captured by Plowden seem to be following in their parents’ footsteps, working in mines, at service stations, and on farms and ranches.

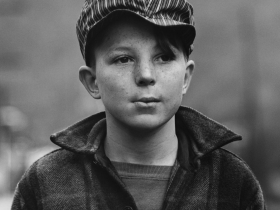

Steve, a 12-year-old resident of Davy, West Virginia, wears a striped miner’s cap, a faraway look in his eyes. Roger, another West Virginia youth, wearing an Exxon jean jacket and patch bearing his name, looks at the camera unsmiling and squinting. Both seem to quietly accept whatever road might lie ahead of them.

Sadly, Plowden notes in one of the narratives that several of the young people were killed after the photos were taken, likely in the mines.

Ranchers in Montana, Wyoming, and New Mexico are photographed against stark backgrounds, prairies and deserts. Several photos, among them “Clyde Gosset on Horse, Watrous, New Mexico, 1972,” could be stills from a John Ford western.

Plowden’s work is a celebration of labor and occupations from a bygone era.

Many of these workers’ livelihoods are endangered today. Modern large-scale agricultural practices threaten farmers and ranchers; manufacturing work is often outsourced overseas; Wal-Mart, Target, Kroger and other big box stores provide steep competition for independent clothing store owners and grocers.

Museum visitors, especially baby boomers and older, may feel the tug of nostalgia while viewing the exhibit. While Plowden is paying homage to these workers, he’s also subtly mourning the changes to these professions and their practicioners over the years.

“Portraits of Work” will run through December 30 at the Milwaukee School of Engineering’s Grohmann Museum, 1000 N. Broadway, Milwaukee, WI.

“Portraits of Work” Gallery

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits, all detailed here.

Art

-

Winning Artists Works on Display

May 30th, 2024 by Annie Raab

May 30th, 2024 by Annie Raab

-

5 Huge Rainbow Arcs Coming To Downtown

Apr 29th, 2024 by Jeramey Jannene

Apr 29th, 2024 by Jeramey Jannene

-

Exhibit Tells Story of Vietnam War Resistors in the Military

Mar 29th, 2024 by Bill Christofferson

Mar 29th, 2024 by Bill Christofferson