A Last Look at Winslow Homer

Milwaukee Art Museum show closes on Sunday. Why you shouldn’t miss it.

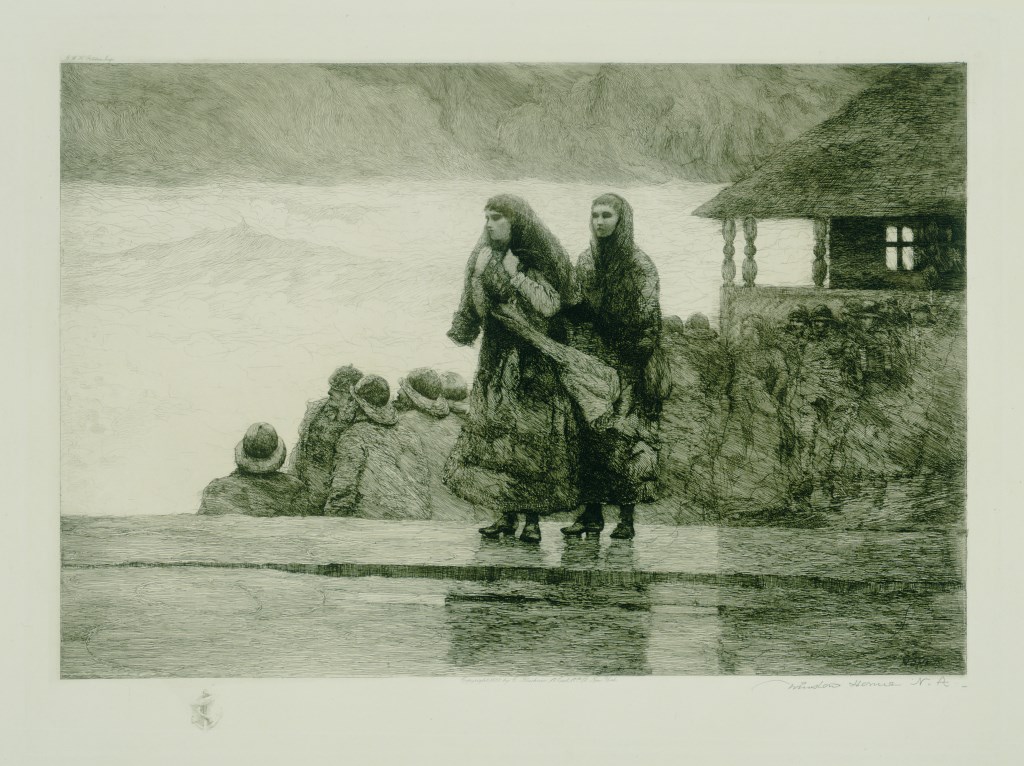

Winslow Homer, Perils of the Sea, 1888. Etching on paper. Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, 1995.38. © Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago / Art Resource, NY

Upon entering “Coming Away: Winslow Homer & England” at the Milwaukee Art Museum, my daughter and I were immersed in digital waves. The projection of a rocky shoreline in high definition on a huge wall greeted us. It was just us and the sea. As we walked past, a wave splashed and my daughter jumped back, startled and giggling.

The first gallery was full of both Homer’s oil paintings and those of his contemporaries and influences. I was struck by Homer’s compositions, the way he set up his paintings, large shapes against glowing backgrounds, silhouettes, single figures or small groups. At first glance, these paintings felt like religious icons, as though some of the figures could have had halos behind them… then I move in for a closer look.

Coming into this show, I had preconceived notions of Homer as just a fair oil painter from seeing his work at other museums. With this show, my feelings did not change. His range of paint handling, ranging from extremely loose, a large brushstroke of white over wet indigo, to a highly refined and rendered hand, are intriguing separately, but left me wishing for a unifying glaze or an extra swipe to merge figure and ground. The figures often feel like they are isolated from the background and could be removed to reveal what I sense Homer really wanted to paint…the dynamism and energy of water. From a distance, most of these paintings glow, but upon closer inspection they reveal too easily how they are made and lack a surface depth and mystery. Which brings me to the the jewel of this exhibition, a painting that is not by Homer but by an artist who died when Homer was still a teenager, JWM Turner’s “Stormy Sea Breaking on a Shore” from 1843.

Near the Turner is the painting, “Song of the Lark” by Jules Breton. The figure stands like a saint with a sickle in front of the luminous, honey-glazed sun. Everything in the painting is toned down to allow the sun, painted bright white and then glazed with semitransparent color, allowing the light to pass through the colored layers, the white ground bouncing the light back to our eyes through the color like stained glass. Lovely.

The remainder of the show is dedicated to Homer and I was pleasantly surprised by his work in other mediums. Homer was a master watercolorist and the simplicity of the medium reveals the work of a great artist which the oils do not. With watercolor, the thin paint absorbs into the paper rather than sitting on top of the primed canvas. The medium itself seems to unify the work in a way the oils don’t and the smallness of scale seems to take the pressure off Homer to make a great and profound painting and to just play. Painting water with colored water also seems to create a flow and the richness of hue and sensitivity of edge in this work is wonderful.

A piece like “Looking Over the Cliff” is a great example of Homer’s ability to capture emotion and light: the dress of the woman in the foreground glows with the lightness of the paper and the edges of the forms play and merge, define and float. A watercolor like “Sunset, Prout’s Neck” is a wonderful example of direct, loose paint application which both embodies the scene and allows Homer’s hand to be revealed.

On to the drawings where the touch and immediacy of the materials, as in the watercolors, cast a favorable light on Homer. I go back to two drawings over and over again: “Men Beaching a Boat” and “Fishermen in Oilskins, Cullercoats, England, 1881.” They both have a simplicity in their making and capture the feeling of the scene though economy and mark making. In “Men Beaching a Boat”, I can picture Homer standing on the beach with his sketchbook at the end of a long day, when all bravado has been washed away by the sea, quickly making this sketch as the last light of day fades. Look at the line that makes the leg of the central figure pushing the boat. In that single line you can feel the weight which sinks a nonexistent foot into the wet sand of the paper. Just below it is a vertical smear of charcoal, which is simply a mark on paper and a sky reflected in the wet sand, simultaneously. In these moments, true alchemy happens.

In “Fishermen in Oilskins” we see graphite, charcoal and white chalk turn into shadows, reflections and light. The fishermen merge in a tangle of shadowed marks. With their backs towards us, they are as intriguing as the ominous light they gaze into.

The last room of this exhibition consisted of mostly oil paintings, but this time there was a notable lack of figures as my daughter took my hand. The energized brushwork in these paintings is allowed to breathe as we walk through crashing waves and sunsets. This gallery is bold and dramatic with high contrast of dark and light. It gives me the sense of the sea’s grandeur, I can smell the salt water as I wade through the painted atmosphere. Like in the entry to the show where one is met with a wall of water, it was just us and the sea. The narrative here was not carried by the figures but by my reaction to the paintings themselves. I was the figure in the work and could better see what Homer saw and feel what he felt as he was alone on the banks of the sea, capturing its salty, evanescent complexity.

“Coming Away: Winslow Homer & England” Gallery

“Coming Away: Winslow Homer & England”, through May 20, at the Milwaukee Art Museum

Todd Mrozinski is an an exhibiting artist at Portrait Society Gallery and currently has a show, From Ten Till Now: A 33 Year Retrospective, at Thelma Sadoff Center for the Arts in Fond du Lac.

Art

-

It’s Not Just About the Holidays

Dec 3rd, 2024 by Annie Raab

Dec 3rd, 2024 by Annie Raab

-

After The Election Is Over

Nov 6th, 2024 by Annie Raab

Nov 6th, 2024 by Annie Raab

-

The Spirit of Milwaukee

Aug 30th, 2024 by Annie Raab

Aug 30th, 2024 by Annie Raab

Song of the Lark, by Breton, has always reminded me of my mother (symbolically, since although she came from a small peasant town in Ukraine she was studying to be a lawyer when, during the war, many villages were raided and all their inhabitants taken away). I too, like you and your daughter, loves the sea splashing in when one first enters!