The Battle Over Great Lakes Water

Big users Nestlé and Waukesha to be joined by Foxconn. Who’s next?

Nestlé water bottle. Photo by Kate Ter Haar. Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0)

Wisconsin is regularly at the center of Great Lakes water politics, but it’s not the only place where controversies arise. Amid intense local and state-level battles over Waukesha’s plan to source Lake Michigan water, and Foxconn’s in-the-works application to use the same at a massive LCD screen factory in Mount Pleasant, these issues attract regional and international attention.

Tapping The Great Lakes, a documentary from Detroit Public TV and Great Lakes Now released in March 2018, offers a bit of perspective by juxtaposing Wisconsin’s water controversies with another in Michigan related to bottled-water operations.

Only days after the documentary debuted, the state of Michigan granted permission to Nestlé Waters North America, part of the Switzerland-based international food and beverage company, to pump even more water from a groundwater well it’s already using within the Great Lakes basin, over fierce public objection. As Nestlé sells this water for profit under the Ice Mountain brand name, residents in Flint continue to suffer the impacts of the city’s water crisis that state officials set off in 2014 with a series of blunders, some of which prompted criminal charges.

Nestlé isn’t drawing water directly from the lakes, but from groundwater instead. Water flows between surface water bodies and underground deposits, so pumping groundwater can impact the levels of lakes, rivers and streams. Nearly the entirety of Michigan is in the Great Lakes Basin, which means all water use in the state is to some extent or other hydrologically bound up with the lakes themselves. It’s quite unlike Wisconsin, which is divided between the Great Lakes Basin and the Mississippi River Basin.

Michigan-based environmental activists including Jim Olson and Peggy Case speak in Tapping The Great Lakes about how, in the 18 contentious years Nestlé has been pumping water in the state (something it had initially hoped to do in Wisconsin), surface waters near the company’s wells have changed.

“The streams are drying up,” Case said. “When you go to the headwaters, at least, so-called monitors there, they claim the water is running at some ridiculous amount, 200 gallons per minute, and what we find is a puddle with stagnant water in it.”

Nestlé’s sale of bottled water both in and out of the Great Lakes Basin would seem to run against the overall spirit of the Great Lakes Compact, which establishes that the lakes are a public trust and that when people withdraw their water, it’s largely supposed to be for residential customers with some level of industrial use.

However, the company has an opening in a provision of the Compact dealing with something called “Bulk Water Transfer.” Its language states: “A Proposal to Withdraw Water and to remove it from the Basin in any container greater than 5.7 gallons shall be treated under this Compact in the same manner as a Proposal for a Diversion. Each Party shall have the discretion, within its jurisdiction, to determine the treatment of Proposals to Withdraw Water and to remove it from the Basin in any container of 5.7 gallons or less.”

Given this rule, if Nestlé or another business wants to sell water sourced within the Great Lakes Basin in small bottles, it’s largely an individual state’s decision whether or not to allow it. The Compact delegates a lot of enforcement power to individual states, including the sale of products containing water under that 5.7 gallon volume threshold.

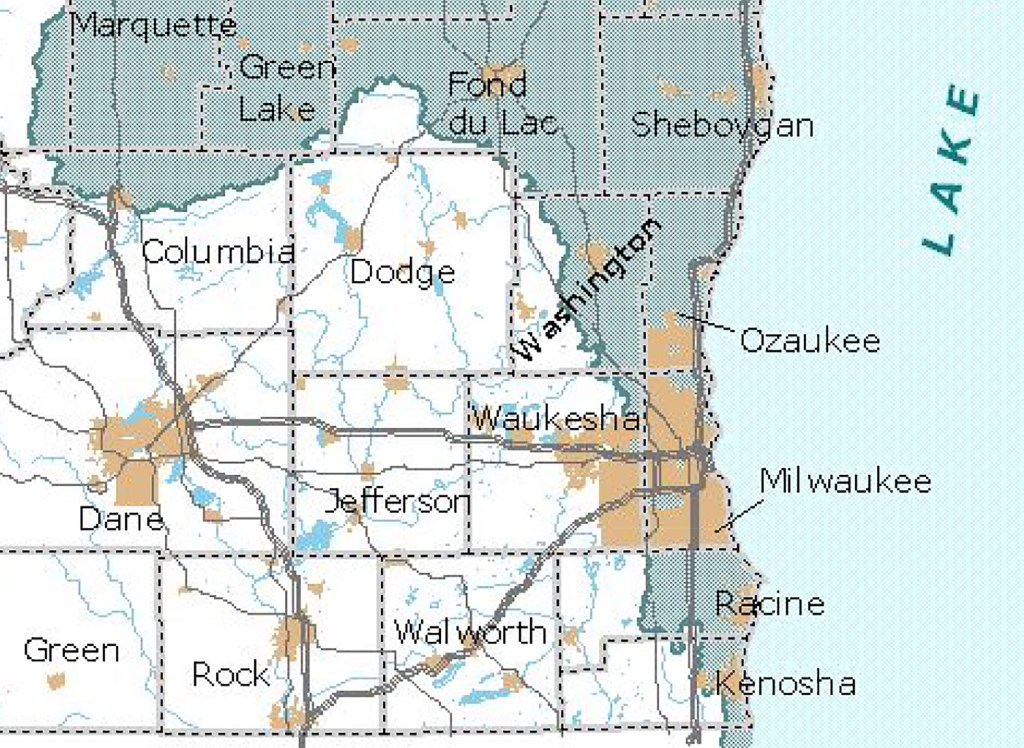

When the city of Waukesha sought to tap Lake Michigan for its drinking water supply, though, it took the unanimous approval of the governors of all eight Great Lakes states, in their capacity as the Great Lakes Compact Council. That’s because the city isn’t in the Basin at all, but is within Waukesha County, which straddles its boundary.

The city of Waukesha is not located within the Great Lakes Basin, but the county straddles its boundary. Map from the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.

Under the Compact, such a straddling-county community can request access to Great Lakes water from the Council, but has to make the case that it doesn’t have a reasonable alternative. Waukesha argued that the radium tainting its groundwater and the depletion of its groundwater supply (which in turn made the contamination worse) left it with no other option. In June 2016, eight state governors agreed.

Both Waukesha and Nestlé frame their water demands as infinitesimal. At an environmental journalism conference in January 2017, Waukesha Water Utility manager Dan Duchniak compared the approximately 8 million gallons per day the city plans to withdraw from Lake Michigan to taking a thimbleful of water from an Olympic-sized swimming pool. And in Tapping The Great Lakes, Nestlé natural resources manager Arlene Anderson Vincent said that “collectively, all the water bottlers account for .01 percent of all the water use in [Michigan].”

Withdrawal of Great Lakes water by people, as extensive as it is, does indeed account for a very tiny portion of the six quadrillion gallons contained in the lakes themselves. Any one user, even a major one like a city or large industrial operation, is only one small portion of that use.

Still, as photos of depleted streams in the documentary illustrate, withdrawals can have a quite visible impact on local watersheds within the Great Lakes Basin. While it would take a truly epic series of human blunders to exhaust a resource as vast as the Great Lakes — actions against which the Compact is meant to guard — there’s always a lingering worry about what would happen to that resource in the long run if more local governments and industries take advantage of the Compact’s loopholes and grey areas.

What happens with more Waukeshas, more Nestlés, more industrial users like Foxconn? One of the underlying assumptions of the Great Lakes Compact is that water taken from the basin will largely be discharged back into it, minus that which people manage to use up in various ways.

These arguments from Nestlé don’t address how water is broadly used, nor its costs. A single household paying its utility bill for drinking, cooking cleaning and bathing water is not a massive publicly traded company with access to various methods of capitalization, and presumably isn’t bottling that water to be shipped elsewhere and sold at a markup. Said household sends a lot, though not all, of the water it uses down the drain, where it leads to a wastewater treatment plant, and ultimately back into the watershed from which it came.

It also isn’t true that people don’t pay for water. Legally speaking, the water of the Great Lakes belongs to the eight Great Lakes states — Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin — and the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec. But that water is regulated to maintain its quality, and enforcing those regulations requires billions in state and federal tax dollars. Additionally, thousands of industrial users around the country get water from public utilities, paying their bills and helping to maintain infrastructure everyone else in their communities depends on. Delivering water from a variety of sources to millions of faucets exacts a cost borne by consumers and taxpayers.

Waukesha’s water use distinctly differs from Nestlé. The city will largely use its Great Lakes access to provide drinking water, and officials admit, without pleasure, that they expect the utility’s customers to pay higher bills due to the infrastructure costs of getting the water to them.

Critics of Waukesha accuse the city not of profiteering, but of not keeping its story straight. Michigan U.S. Rep Debbie Dingell, D-Dearborn, said in Tapping The Great Lakes that Waukesha started out claiming that it needed Lake Michigan water because of radium contamination, not because of the depletion of those groundwater reserves. Duchniak countered that it’s both issues. Indeed, they are intertwined; as groundwater volume decreases, naturally occurring radium taints it at increasing concentrations. Meanwhile, opponents of the Waukesha diversion state in the documentary that there’s evidence that the area’s groundwater reserves have rebounded a bit since the turn of the century.

During the Great Lakes Compact approval process, Waukesha had to compromise on plans to expand the geographic area its water utility would serve.

“What became highly contentious was when they initially proposed this diversion, they requested to add additional communities to their water supply district, and it started to look like kind of an economic-growth type of project rather than just a water supply for people that needed it because their groundwater was contaminated,” Wayne State University Law School professor and Transnational Environmental Law Clinic director Nick Schroeck said in the documentary.

In 2010, Waukesha asked to use 10.9 million gallons per day — far more than it’s using in 2018 — then walked their request back to 8.2 million gallons per day and proposed using it in a smaller service area. That’s what the Compact Council eventually approved. Schroeck called it a “very good middle of the road decision,” while also pointing out its political implications.

“Waukesha was on the minds of the drafters of the Compact when they agreed to this document … you had to pass it in Wisconsin, so you needed some provision for a politically powerful community in the state to agree to allow this legislation to go forward,” Schroeck said, hinting at Waukesha County’s status as an influential Republican stronghold.

As different as the particulars are, both Nestlé and Waukesha point to bigger questions about the future of water resources in the Great Lakes. How should states apply and interpret a relatively new but legally binding agreement? Are the few interpretive decisions made under the Great Lakes Compact so far setting the right precedents? Do the Compact and state and federal laws make it too easy for businesses and certain communities to misuse a resource that belongs to the people of the Great Lakes Basin?

As Geist notes at the end of Tapping The Great Lakes, these two disputes may have only set the stage for many other, equally or more fraught conflicts: “It’s hard to imagine a future in which there will be no future requests for water diversion from those in need, whether they be from close neighbors or distant interests.”

Water Battles Straddle The Great Lakes Basin was originally published on WisContext which produced the article in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television and Cooperative Extension.

Waukesha ruined their aquifer after decades of abuse and b9 conservation.

They do not deserve to get Michigan water.

It’s the logical end to Republican policy.

Dump Walker and republicans.

They have crapped on Wisconsin and polluted our environment.

The article fails to provide the “context” it promises. Waukesha will not have a negative impact on the volume of water in the Great Lakes Basin. It will return the same amount it withdraws. The approval by the 8 Great Lakes states says “approximately 100% of the volume withdrawn from the Basin will be returned via flow through the Root River, a tributary of the [Great Lakes] Basin. This will effectively result in no net loss of water volume to the Basin.” Waukesha is essentially recycling water back to the source.

The Great Lakes states also found that the groundwater Waukesha currently uses is connected to Great Lakes Basin groundwater, so ending its use of groundwater will actually create a positive impact on the volume of water in that Basin. The city’s current water use “draws groundwater away from the Basin” without being returned. The switch from groundwater to Lake Michigan surface water “will result in a net increase of water in the Lake Michigan watershed,” the approval says.

Waukesha will not deplete streams. Ending the use of groundwater will help preserve them. And sending return flow down the Root River creates a significant added benefit. The approval found that Waukesha’s high quality “return flow will benefit a Basin tributary, the Root River . . . Increased flow will result in an improvement of the fishery and benefits to the Basin salmonid egg collection facility located downstream on the Root River.”

Nestlé sucks

Bill, there are certainly differing views on the rubber-stamped approval you’ve largely posted verbatim. There were multiple reports (linked at bottom of this comment) that Waukesha could have treated water from its existing wells for radium at far lesser cost than building infrastructure required for a diversion. There are over three dozen Wisconsin communities that successfully treat their water for radium without diverting Great Lakes water. I also recall reading multiple reports that conflicted with the city’s self-serving analysis that return flow would actually benefit the Root River.

From a bigger picture though, Waukesha was given notice of its violation of radium guidelines by the DNR all the way back in 1987, and they entered into a compliance agreement whereby they were required to achieve compliance with the state’s clean water standards. They were then ordered to do so by the EPA in 2000, and the DNR in 2009. All told, they had 30 years to do what any responsible city does with a water problem, yet they failed and refused to do so. The Great Lakes should not be viewed as a fallback water supply for reckless municipalities that happen to straddle the water basin – this lets similarly situated cities know they can neglect their infrastructure for decades and just apply for a diversion when shit hits the fan.

static1.squarespace.com/static/55845d9de4b0b4466f1267b9/t/55b26a8de4b0f414ae482ea3/1437756045901/Non-Diversion+Alternative+Report_City+of+Waukesha+Water+Supply_Full.pdf

@joe- it’s exactly that kind of tunnel vision that will ultimately put the Great Lakes in jeopardy from threats of a water crisis in southern and western states. The rejection of a reasonable case like Waukesha’s would have caused the entire agreement to come under question. It’s critical that supporters on all sides prove the compact works. Waukesha’s case has done that. The return of the lake water is the key to preserving the watershed. Once you begin to contemplate returning water from hundreds of miles away you make the idea of shipping water out of the basin cost prohibitive. As well, you cannot underestimate the benefits to the lakes that will be a result of taking Waukesha off the aquifer. Not only will the aquifer be replenished, assuring smaller communities will not need to tap into the Great Lakes, but there will be a net GAIN of groundwater flowing back into Lake Michigan as the aquifer replenishes. This is in addition to the benefits to the regions surface waters as Waukesha’s growing needs would have harmed wetlands, rivers and streams. If one looks at the problem as a whole, it’s easy to see that the greatest benefit, and lesser threat, to the environment was through the approval of a great lakes diversion.

Galeb, your post inappropriately presumes that Waukesha’s request was “reasonable.” The Compact requires any diversion applicant to show that there is “no” feasible, cost-effective alternative water supply. It is clear that treating water for radium would have been feasible and cost-effective. The fact that the compacting states were convinced otherwise shows me that the Compact is already being proved to be meaningless.

Watch FoxConn steal another 7,000,000 gallons/day even though their plant will largely be outside the basin, by sneakily becoming a “customer” of Racine who is within the basin. No, I do not think there is a risk of places like Arizona coming for our water – but if you think for a second that either of these diversions live up to the spirit of the Compact, i find that to be ludicrous.

@joe – keep pretending that the Compact is a license to deny any application and watch Congress intervene and eliminate any protection. What’s ludicrous is the argument that eight states (most that have nothing to gain from approval) can unanimously approve an application that has no merit.

I’m not pretending anything. The default rule in the Compact is that diversions are not allowed. Exceptions to that rule are called “exceptions” in the Compact and they must meet strict criteria which I referenced in my previous post. Perhaps you should read it sometime.