Lake Superior No Longer Clearest Great Lake

Lake Huron first, Lake Michigan second. Why the historic change?

![Lake Huron, the clearest Great Lake. Photo by Hgjudd (Self-published work by Hgjudd) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or CC BY-SA 2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5-2.0-1.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://urbanmilwaukee.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Lake_Huron-768x576.jpg)

Lake Huron, the clearest Great Lake. Photo by Hgjudd (Self-published work by Hgjudd) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or CC BY-SA 2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5-2.0-1.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Lake Huron — now in 1st place — and Lake Michigan in the 2nd spot have bumped Superior down to 3rd place, a new study of water clarity in the Upper Great Lakes shows. Lakes Erie and Ontario trail all three.

“This is a change of significant historical and economic importance,” according to the study by scientists at Michigan Technological University, the University of Michigan, University of California Los Angeles and Colorado State University. “More important may be the ecological implications of the large increases in water clarity in lakes Huron and Michigan.”

Those include changes in the distribution and behavior of vertebrates and invertebrates such as spiny water fleas and other crustaceans.

The study published in the Journal of Great Lakes Research identified three principal factors:

One is a reduction in phosphorus entering lakes Huron and Michigan, largely from agricultural run-off of fertilizers. Heavy phosphorus levels can create algal blooms, such as the one in western Lake Erie that shut off Toledo’s water supply in 2014.

The second is the proliferation of the invasive quagga mussels that feed on plankton as they filter the water of the lakes. The National Wildlife Federation reports that the estimated 10 trillion quagga and zebra mussels that blanket the lakes’ bottom “have succeeded in doubling water clarity during the past decade.”

While both types of mussels filter water, quaggas have the greater impact because they can survive in deeper and colder waters, said Robert Shuchman, co- director of the Michigan Tech Research Institute in Ann Arbor and a co-author of the study. “Their sheer numbers are the dominant filtering mechanism for water quality.”

The third factor is climate change, which has a more indirect impact on water clarity, Shuchman said.

For example, warming water temperatures in Lake Superior could open the door for the arrival of invasives there, he said. And climate-driven extreme weather events, spring floods and farm field runoff can increase the amount of phosphorus entering rivers that empty into the Great Lakes.

Increased water clarity isn’t necessary a good thing.

According to the National Wildlife Federation, “Clearer water allows sunlight to penetrate to the lake bottom, creating ideal conditions for algae to grow” and thus enables the “growth and spread of deadly algal blooms. Algae foul beaches and cause botulism outbreaks that have killed countless fish and more than 70,000 aquatic birds in the last 10 years.”

In addition, the organization says, “Clear water may look nice to us, but the lack of plankton floating in the water” because of hungry quagga and zebra mussels “means less food for native fish.”

Shuchman said, “It is disruptive to the food web. You go from one-cell algae all the way up to the game fish people like to catch.”

Another negative: Clearer water promotes the growth of submerged aquatic vegetation, a native plant known as Cladophora that resembles angel hair underwater. Shuchman said poor water quality used to limit it to a maximum depth of about 20 feet but improved clarity lets it grow to as deep as 60 feet.

“Storms come in and it literally gets ripped off its root mechanism and then ends up going on the beach,” as has happened at Sleeping Bear National Lakeshore on Lake Michigan. “It smells bad but also caused botulism and some major avian kills of seabirds,” he said.

This story was originally published by Great Lakes Echo.

Great Lakes Echo

-

Tracking Balloon Debris in Great Lakes

Dec 3rd, 2019 by Tasia Bass Cont

Dec 3rd, 2019 by Tasia Bass Cont

-

Coal Ash Pollutes Midwest States

Jun 5th, 2019 by Andrew Blok

Jun 5th, 2019 by Andrew Blok

-

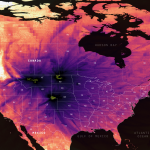

Extreme Changes Forecast for Great Lakes

May 21st, 2019 by Cassidy Hough

May 21st, 2019 by Cassidy Hough