“We Fought Just As Hard”

The role of women in the Milwaukee’s open housing marches of the 1960s.

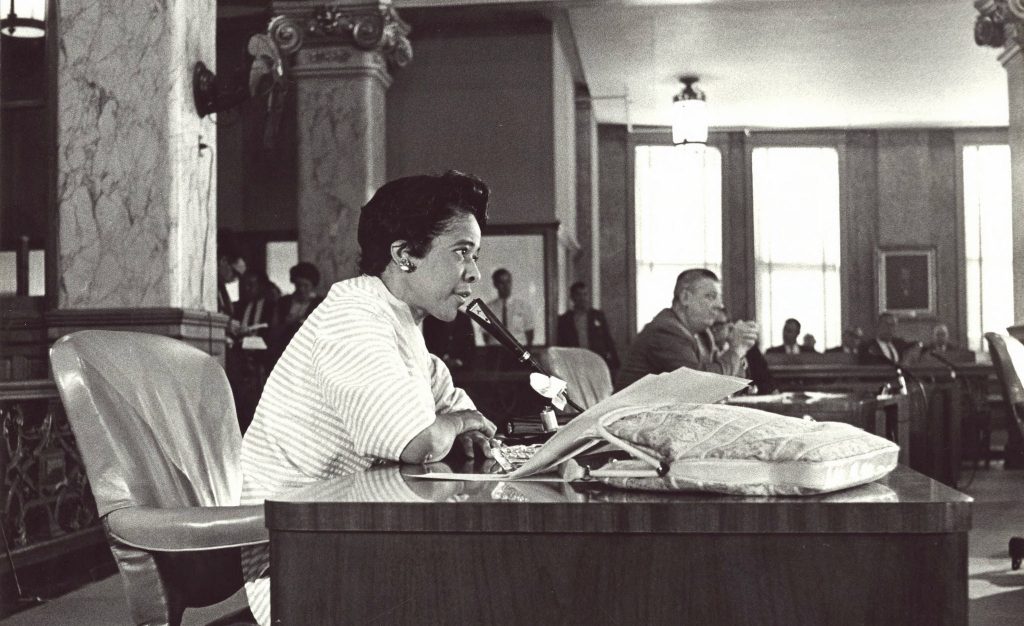

Councilwoman Vel Phillips speaks at a Milwaukee Common Council meeting in 1970. Archival image from the University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project.

Deborah Campbell Tatum was just a young girl when the civil rights movement began to sweep the nation, but her involvement in the fight for open housing in Milwaukee changed her life forever.

“When the open housing march[es] started, it was the first time I saw [African-Americans] come together as a race of people, and just people…coming together. It was all colors,” said Tatum. “Being a child, to see that was lovely. I never missed a day. That was the beginning of my political life.”

In Milwaukee, Velvalea “Vel” Phillips was setting an example for African-American women and girls with political aspirations. The first woman to graduate from University of Wisconsin-Madison Law School, the first woman and African-American member of Milwaukee’s Common Council, the first woman and African-American elected secretary of state in Wisconsin: Phillips demonstrated to all what African-American women could accomplish in politics, and set the stage for black women to leverage political power.

Phillips first proposed an open housing ordinance in 1962. Despite several attempts, the council failed to pass the ordinance for the next six years. It took the 1968 Fair Housing Act, passed by Congress a week after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., for the Common Council to approve a fair housing law in Milwaukee.

As Phillips was fighting for civil rights as a member of the council, the Milwaukee NAACP Youth Council, founded in 1947, provided leadership opportunities for young women that were absent in other aspects of their lives, according to Dr. Erica Metcalfe, a Milwaukee native and assistant professor at Texas Southern University, who earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. It was under the leadership of the Youth Council’s first president, Susan Warren, that the chapter was nationally recognized for activism in the 1950s. Other young women also served as Youth Council presidents.

“Girls were empowered by the leadership skills that membership within the Youth Council afforded them,” Metcalfe wrote.

Alberta Harris Moore, a high school student at the time, played a fundamental role in the open housing movement and facilitated the collaboration between the Rev. James Groppi and the Youth Council, which she served as president. Moore first met Groppi as a student at St. Boniface Church School.

“Father Groppi was so in tune to how I envisioned the Youth Council to be — an organization involved in direct action,” said Moore, now 71. In 1965, the group’s advisor was thinking of leaving. “I asked if he [Groppi] would consider being our advisor. At first he said no, but I persisted. He decided he’d come on temporarily until we found another advisor. He never left.”

Father James Groppi and Vel Phillips stand atop the hood of a bus, surrounded by members of the Milwaukee NAACP Youth Council. Archival image from the University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project.

Groppi encouraged Moore’s cousin, Vada Harris, to become involved in the movement. One of the first African-American students to attend the predominately white Riverside University High School, Harris, now deceased, led a “textbook turn-in” protest in which she and other students returned their history books and walked out of class to challenge the exclusion of African and African-American history.

In 1966, however, the dynamic shifted. The Commandos, formed partially in response to threats and bombings, emerged as a new male security unit intent on protecting protesters from violence and representing African-American men in a distinguished light.

“When the marches reached the highest numbers, a lot of new [men] joined. [Many] were veterans who had finished their enlistment period,” said Margaret Rozga, a former member of the Youth Council who later married Groppi. She added that at that point the direct action committee, which was responsible for developing strategy and taking part in protests, took a more central role. “Within that group was the Commandos, [which] was all male,” Rozga said.

Still, Rozga said, the environment was friendly and comfortable for female members.

“Other voices were still respected,” she added. “There were lots of opportunities for discussion so it wasn’t an antagonistic atmosphere at all.”

“In Milwaukee, we were hand-in-hand with men involved,” agreed Moore. “I feel females were a big driving force in the movement. I never felt that we weren’t equal partners in what was going on in the movement, even on the national level.

Some young women in the Youth Council, however, were unhappy with the Commandos’ all-male leadership and proposed a vote to include women. Nearly every male in the council voted against the proposal.

“What that said to the female members was that the role of protector was reserved for men,” said Metcalfe. “People had a kind of egalitarian philosophy when it came to race but didn’t have that same philosophy when it came to gender, that males and females should have the same opportunities.”

“Being treated as a man, having this image of strong black manhood, was very important to [the Commandos],” Metcalfe said. “It was also important to them because of Father Groppi. He was a white male and some people looked at that [and said], ‘You’re not even leading your own movement.’ They needed to create a unit that embodied black male leadership.”

In the wake of the failed vote to include women in the Commandos, Youth Council member Mary Arms, who had come up with the name Commandos, suggested creating the “Commando-ettes,” an informal female counterpart unit.

“We fought just as hard. We were right there by their side,” said Arms in an interview for the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee’s March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project. “We felt like we needed a name but it didn’t really stick with us.”

She said the Commando-ettes were responsible for leading songs and chants to keep up momentum during the marches, as well as monitoring for agitators or police plants seeking to cause a disturbance. “We didn’t really do too much of anything but parade back and forth,” Arms said.

For many, Metcalfe said, civil rights became “a family thing,” that built camaraderie among relatives and friends. Mothers and grandmothers fed protesters and made sure that the young women were being treated well.

“At that time, the race issue kind of overshadowed the gender issue. The young women…let the situation with the Commando-ettes go,” said Metcalfe. “They felt that their issues had to be put to the side because of the [focus on] race.”

The familial nature of activism, however, still remains strong today. Tatum’s daughter, Chantia Lewis, is now an alderwoman in the 9th District.

Lewis credits her mother with instilling in her a passion for justice. “I would not have my activism spirit without [her] and the work that [she] put in,” she said.

Glad to hand her torch to the next generation of leaders, Tatum is proud of the legacy she and the NAACP Youth Council established. “I started, but now my daughter is moving forward,” she said.

Editor’s note: Jenny Fischer contributed to this article.

This story was originally published by Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service, where you can find other stories reporting on eighteen city neighborhoods in Milwaukee.

50 Years After The Marches

-

Pandemic Shines Spotlight on Workers’ Struggle

Sep 7th, 2020 by Erik Gunn

Sep 7th, 2020 by Erik Gunn

-

UW System Expects $212 million in Losses

![Van Hise Hall in the background. Photo by James Steakley (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://urbanmilwaukee.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/1017px-Ingraham_Van_Hise_carillon-185x122.jpg) May 8th, 2020 by Rich Kremer

May 8th, 2020 by Rich Kremer

-

51 of 72 Counties Now Back Fair Maps

Apr 15th, 2020 by Matt Rothschild

Apr 15th, 2020 by Matt Rothschild

Thank you for this story – this is why Urban Milwaukee is my favorite news source.