The Battle for Juneau Park

How a long-running “war on perversion” gave birth to gay pride

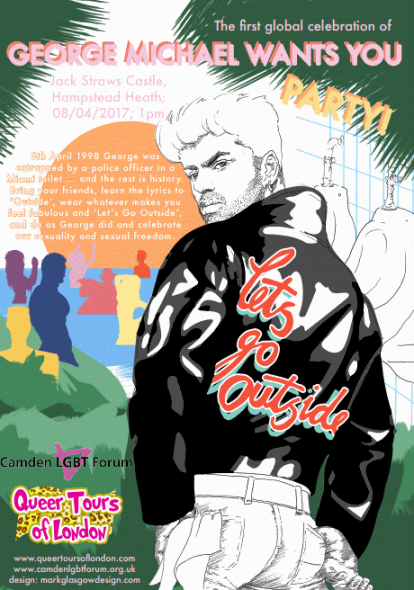

Last weekend, Queer Tours of London hosted George Michael Wants You, a “sexual freedom party” honoring not only the late singer’s passing, but also the 50th anniversary of the first decriminalization of homosexuality in the United Kingdom. More then 1,300 people also signed a petition asking the City of London to install a tribute bench in George Michael’s honor.

“George Michael still found it impossible to be open about his sexuality in the late 1990s,” reads the group’s press release. “His sexuality was used to both criminalize and humiliate him…so we want to use this celebration of one of the community’s finest to continue to challenge the barriers that still remain.”

Hampstead Heath, one of the largest and oldest green spaces in the U.K., has a long and often sordid history as a gay cruising park, of “Going up the Heath” as it was known. George Michael was caught here in 2006 by U.K. tabloid News of the World, eight years after being outed by an indecent exposure arrest in Beverly Hills.

Why was one of the most famous musicians of his era cruising for sex in a public park? During a 2009 interview, the Daily Mail asked Michael exactly that. His answer: “I do get anyone I want, but I like a bit of everything.”

For many gay people in Milwaukee, cruising an area like Juneau Park was the only way to have any type of authentic sexual identity at all.

The Origins of Cruising Culture

Cottaging. Tea-rooming. Cruising. Whatever you call it, it revolves around men hunting for anonymous, casual sex in a public place: parks, public restrooms, rest stops, backrooms, alleyways, anywhere clandestine enough to feel edgy. Make no mistake: it’s very illegal, it’s very dangerous, and it can be very damaging for those who get caught.

Middle America was first introduced to this subculture in 1980, when Al Pacino starred in the controversial film Cruising. The film was widely criticized not only for being exploitative, but also for linking homosexual attraction with psychotic, murderous urges. New York’s LGBTQ community viciously protested the film before, during and after production. Director William Friedkin eventually released a disclaimer stating, “This film is not intended as an indictment of the homosexual world. It is set in one small segment of that world, which is not meant to be representative of the whole.”

Anyone condemning our elders for living heavily sexualized lives just doesn’t understand the historical context. For many men, these fleeting, anonymous moments were all they would ever have. There was no real option to go public or maintain a long-term relationship. There was no easy way to join a society that was as invisible from the outside as it was guarded from the inside.

If not for the cruising arrests – widely publicized and certain to include their full names and addresses — we might never know that these meeting spaces existed. Milwaukee has exorcised many historic hotspots: the former “Fruit Loops” in Cathedral Square, the Third Ward, and Walker’s Point; downtown department stores; SRO hotels; university restrooms; and adult bookstores have all been either erased or cleansed of their former reputation.

Try as they might, they still couldn’t erase them all. One of the longest-running cruising destinations still exists today. It holds the historic distinction of being the only civic space ever defended against homosexuals by a public official. “The park is hot!” became not only an invitation, but a rallying cry.

Yes, I’m talking about Juneau Park.

Judge Seraphim and Juneau Park

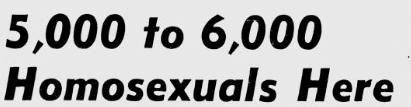

5,000 to 6,000 Homosexuals Here. Headline from the Great Gay Panic of 1963 from the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel Archives.

Juneau Park, among the oldest of Milwaukee’s county parks, was dedicated in 1872 as a “breathing lung” to the congested industrial city. Originally, railroad tracks ran along the bluff, but wooded trails to Lower Juneau Park were added in the 1930s.

By 1959, Yankee Hill’s Victorian mansions were being replaced by apartment buildings, and Juneau Park had become a shadowy refuge. Following a sensational 10-man bust in Waukesha’s Frame Park, Milwaukee Police became obsessed with an “undesirable” and “potentially dangerous” pattern.

Between 1962 and 1963, a quarter of the city’s disorderly conduct arrests happened in Juneau Park, and the number was growing every month.

“Juneau Park has become a hangout for homosexuals,” said MPD Sergeant Walter Heller, apparently fearing a recruitment drive. “One of the sad results is that it has attracted young persons drawn out of curiosity. This could result in them becoming a sex deviate.”

“Look, if you were in Juneau Park, you were automatically fair game. You wouldn’t be there unless you were looking,” says Bunny, a Wisconsin LGBT History Project contributor.

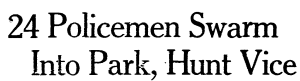

Judge Christ T. Seraphim called for a public “war on perversion” and pledged to “make the park safe for children.” Up to 24 undercover detectives patrolled the tiny park nightly, and their tactics often involved entrapment, coercion and violence. The park became a battleground with real life casualties.

24 Policemen Swarm Into Park, Hunt Vice. Headline from the Great Gay Panic of 1963 from the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel Archives.

One of those casualties was Elroy Schulz, brewery worker, who was arrested in Juneau Park after supposedly grabbing a vice officer and making an “immoral proposition.” A divorcee and ex-convict with sodomy charges on his record, Elroy had the misfortune of meeting the police department’s boxing champion.

Vice squad detectives claimed that Elroy resisted arrest. In the process of being “arrested,” Elroy suffered shattered dentures, diabetic shock, abdominal bleeding and a brain hemorrhage – although the officer claimed to hit him only once. He died before sunrise, less than five hours after his discharge. His killers were, remarkably, cleared of all charges of excessive force.

“The officer acted justifiably and excusably in the due process of the law and could not be held criminally responsible,” read the inquest. “No charges will be filed.” There were no protests, riots, or civil lawsuits for Elroy Schulz.

“People can’t understand a problem they don’t see. We see them – these men are predatory. They hang around theaters, stores and public restrooms. They are a threat to public decency,” said a veteran police officer.

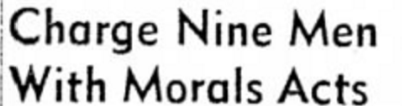

Schulz’s death was a chilling reminder to expect no mercy. Gay men were already bombarded with messages that they were indecent, immoral, and dysfunctional. They were considered second only to prostitutes as a public health menace. They were threatened with being institutionalized until proven “cured” of their “condition.”

Charge Nine Men With Moral Acts. Headline from the Great Gay Panic of 1963 from the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel Archives.

“For most of the hidden homosexuals, it is a furtive, lonely life of passing attachments, a life haunted by fear of exposure, loss of job, blackmail and perhaps guilt. It is gay only in homosexual jargon,” said the Milwaukee Sentinel in 1960.

Rather than being scared into hiding by police brutality, criminal records or social shame, Milwaukee’s gay community defiantly emerged from the darkness. Bars began opening all over the city, creating a network of safe spaces that fostered unity, activism and ultimately, liberation.

“They now want it believed that homosexuality is not just an acceptable way of life, but rather a desirable, noble, preferable way of life,” remarked the Milwaukee Journal in May 1964. “The homosexual has gotten bolder.”

“If we were going to hell anyway,” says Bunny, “we were going to hell in high heels. Let nothing more stand between us and our fun.”

The battle for Juneau Park ended with no real winners. Under civic pressure to reduce excessive police costs, Judge Seraphim eventually abandoned his warfare. The LGBTQ community ultimately reclaimed Juneau Park, which hosted the city’s first “Gay In” in 1973 and PrideFest from 1991 to 1994. Many gentlemen of a certain age met their long-time partners and husbands in Juneau Park – even if few will openly admit that.

The park continued to thrive as a hookup hotspot well into the 1990s, despite endless cycles of police and media attention. Nothing could stop the night market: not locking the restrooms, not removing the hillside foliage, not even bicycle cops patrolling the paths. When cruising culture moved online, and later to apps, all twilight traffic vanished from the park.

Today, it’s almost unthinkable that anyone would ever need to defend the park’s honor. Of course, we have no real concept of what it meant to be a sexual outlaw in a world that hated everything about us. We have no sense of the bravery and boldness that was required for people just to exist. We have no idea how it felt to live silently because living out loud would be a criminal act.

Thanks to these adventurous elders, we no longer have to find anonymous love in dark and dangerous places. Maybe it’s time for a sexual freedom party in their honor.

Out Look

-

The Enduring Legacy of Eldon Murray

Aug 1st, 2019 by Michail Takach

Aug 1st, 2019 by Michail Takach

-

The Flag Stands for LGBTQ People, Too

Jul 4th, 2019 by Michail Takach

Jul 4th, 2019 by Michail Takach

-

The Evolution of Drag

Mar 30th, 2017 by Michail Takach

Mar 30th, 2017 by Michail Takach