ACLU Suit Challenges Milwaukee Police

Charges key technique, “tens of thousands" of police stops, is unconstitutional.

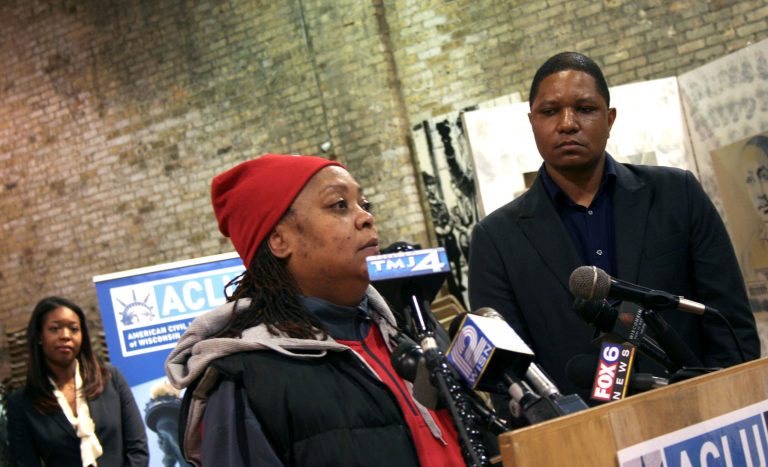

Plaintiff Tracy Adams (center) talks about her son being stopped by Milwaukee police as ACLU of Wisconsin Police Accountability Specialist Jarrett English (right) looks on. Photo by Jabril Faraj.

Tracy Adams’ son was 11 years old the first time he was stopped by Milwaukee police. The boy was at his friend’s front door when an officer who had driven through a nearby alley asked him to come down off the porch; the officer didn’t say why, according to Adams.

“The police officer came up on the porch and guided him towards the car, took the phone out [of] his hand — his cell phone — put it up on top of the squad car and then proceeded to pat him down,” said Adams, who is black. “That was his first stop.”

It happened two more times, once when the boy was walking through an alley after leaving a friend’s house and while on the way to school. In all three instances, he was detained without reason and released without receiving a citation, according to the suit.

“Every time my son leaves the house I’m worried. I’m worried until he comes back home and I know he’s safe,” she said. “I’m standing with him, standing with other African-American mothers who have to tell their sons constantly, ‘When you [are stopped] by the police officers, be calm, answer their questions, cooperate and you may come home alive.’”

On Wednesday, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and ACLU of Wisconsin announced a federal class action lawsuit, Collins v. City of Milwaukee, challenging what they called “the unconstitutional [and] suspicionless stop-and-frisk program of the Milwaukee Police Department.” Adams, a plaintiff in the case, made her remarks during a news conference at the Milwaukee Black Historical Society. The suit also names the Fire and Police Commission and Milwaukee Police Department (MPD) Chief Ed Flynn as defendants.

Charles Collins, 67, a military veteran and retired Certified Nursing Assistant for Milwaukee County, is the lead plaintiff in the case. Collins, who is black, recounted a traffic stop for which police did not give a reason, purportedly ran a warrant check and returned his ID without issuing a ticket or warning. Collins, who has lived in Milwaukee for 55 years, said he is constantly looking over his shoulder for police officers.

“It’s kind of an anxiety — I’m on edge,” he said.

Four other plaintiffs — Greg Chambers, a 32-year-old black man; Caleb Roberts, a 24-year-old Milwaukee native attending graduate school in Texas; Stephen Jansen, 29, who has a master’s degree from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee; and Alicia Silvestre, a 60-year-old Latina woman who has worked in Milwaukee Public Schools for more than 30 years — are also named in the suit. Plaintiffs are seeking improved training, supervision, discipline and monitoring of officers; they are also demanding the regular release of data regarding stop and frisk incidents to ensure accountability.

MPD Chief Ed Flynn speaks to reporters Thursday at Police Headquarters downtown. Photo by Jabril Faraj.

The suit alleges MPD’s policies and practices violate the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution’s requirement that an officer must have a “reasonable suspicion of criminal activity” to make a stop and a “reasonable suspicion that a person is armed and dangerous” to frisk an individual. It also claims the department’s practices violate the Fourteenth Amendment and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which guarantee equal protection and prohibit discrimination based on race, color and national origin.

At a news conference Wednesday, MPD Chief Ed Flynn “categorically and unequivocally” denied the allegations, citing that most of the violence in Milwaukee occurs in central city neighborhoods, which are overwhelmingly poor and non-white. He defended the department’s strategies and tactics, noting the goal is to deter crime, not “revenue-raising, harassment or the imposition of fines and warrants on people unable to pay them.” Officers are encouraged to make traffic stops, and to engage pedestrians, but often release people without a fine or ticket, according to Flynn.

“An active police department that gets out of its cars … affects perceptions of safety — it affects the fear level, it affects the fact that people believe those public spaces are being watched,” he said.

“The department has made no secret of its intentions to flood communities of color with police officers whenever parts of those communities are deemed to be hot spots for crime,” said Jason Williamson, ACLU Criminal Law Reform Project senior staff attorney. He noted, “Crime rates, or the occurrence of a particular crime, do not give the police license to ignore the Constitution.”

Williamson said, in addition to the accounts of the six plaintiffs, he and others spoke with “hundreds of ordinary Milwaukeeans” particularly black and Latino individuals who expressed “outrage, anxiety, deep frustration and a profound sense of sadness” regarding interactions with MPD during a nearly three-year investigation. In addition, ACLU lawyers attended public community gatherings, town hall meetings, public safety committee meetings and listening sessions where citizens raised similar concerns, according to ACLU of Wisconsin Senior Staff Attorney Karyn Rotker.

Flynn said that MPD does not engage in “stop-and-frisk” practices, stating that vehicle stops are made as the result of traffic infractions and department frisk policy is “grounded in constitutional principles,” meaning that officers must have “an articulable suspicion to frisk someone.”

He said MPD’s strategy was different than that of New York police, whose “stop-and-frisk” practice was ruled to be unconstitutional by a federal judge in 2013 for reasons similar to those cited in the Milwaukee suit.

Based on a preliminary review of MPD data concerning police stops between 2010 and 2013, “tens of thousands of records” do not provide an adequate reason for the contact, according to Nusrat Choudhry, the lead attorney on the suit. She said more than 50,000 instances listed “suspicious person,” “suspicious vehicle,” “none” or other “vague descriptors” as reasons for the stops.

“None of these purported reasons demonstrate that an officer had reasonable suspicion of criminal activity that could justify the stop. And that is what the law requires,” Choudhry said.

Chambers, who police questioned on three separate occasions without cause, according to the suit, called the practice “a kind of targeting that has been geared towards people of color.

“As a person who does his best to stay out of trouble, it seems that, in these particular instances, there was no way I could avoid it.”

Rotker said these practices also undermine MPD’s relationship with minority communities and compromise its ability to investigate offenses and decrease crime in these communities. Choudhry said reform is necessary to rebuild that trust.

Choudhry added, “It’s time that the Milwaukee Police Department … took action, to bring their practices in compliance with the law.”

This story was originally published by Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service, where you can find other stories reporting on fifteen city neighborhoods in Milwaukee.

More about the Stop-and-Frisk Lawsuit

- Milwaukee Hires New Monitor For Policing Settlement - Jeramey Jannene - Feb 16th, 2026

- Five Years After Settlement, Racial Disparities Remain In MPD’s Practices - Edgar Mendez - Nov 10th, 2023

- Black City Residents Still More Likely to Be Stopped, Frisked by Police - Evan Casey - Sep 26th, 2023

- Joint Statement from the Mayor, FPC and MPD - Mayor Cavalier Johnson - Sep 22nd, 2022

- Collins Settlement Agreement Report Highlights MPD’s Significant Improvement - Milwaukee Police Department - Oct 28th, 2021

- Report Finds Continuing Police Bias - Gretchen Schuldt - Sep 26th, 2021

- Police Haven’t Ended Stop and Frisks - Isiah Holmes - May 4th, 2021

- Police Stops Still Biased, Report Shows - Gretchen Schuldt - Sep 26th, 2020

- City Hall: Mixed Results on ACLU Settlement Compliance - Jeramey Jannene - Mar 26th, 2020

- City Hall: Committee Demands Stop-and-Frisk Plan - Gretchen Schuldt - Mar 2nd, 2020

Read more about Stop-and-Frisk Lawsuit here

This whole thing makes me sad. I actually think, Flynn is one of the more reasonable cops out there (Unlike the crazy-pants sheriff) but I do suspect unreasonable searches are going on. Wouldn’t the ACLU accomplish more by working out a deal and creating some kind of dialogue than by trying to pull money out of an already cash strapped city?

” She said more than 50,000 instances listed “suspicious person,” “suspicious vehicle,” “none” or other “vague descriptors” as reasons for the stops.”

Those are how people get categorized when caught by our neighborhood watch or other residents prowling through alleys, backyards, etc looking for a target to rob, burglarize, steal, etc.

Working out a deal with the department Tyrell? How would that work? Is it possible that was attempted?

What troubles me is the admission by law enforcement that most stops do not result in arrest or a ticket. How does that help build strong relationships with the residents of these communities? Doesn’t it sow distrust between those residents and law enforcement? I am not saying crime isn’t a problem in those neighborhoods, and I believe the vast majority of the residents of those neighborhoods are deeply concerned about crime. And I agree that Flynn seems like one of the more reasonable cops out there (especially compared to grandstanding egomaniac lunatic Clarke). But isn’t it reasonable for residents of these communities to feel that all these stops without arrest or ticket are more like harassment and less like building productive community relations while stopping crime?

RE: Wouldn’t the ACLU accomplish more by working out a deal and creating some kind of dialogue than by trying to pull money out of an already cash strapped city?

Unfortunately, in such situations, the only way you can start such a deal-making dialogue is to get the attention of the police via a civil suit. The plaintiffs here are not seeking a monetary remedy, bur, rather ” improved training, supervision, discipline and monitoring of officers; they are also demanding the regular release of data regarding stop and frisk incidents to ensure accountability.” A large number of lawsuits are settled out of court, which is, as it were, the establishment of the negotiations for a deal such as the one that TTM seeks. The ACLU came in because the plaintiffs were able to convince it that violations of constitutionally-protected rights were taking place with considerable frequency. The frequency of news stories in which such stops and searches, both unreasonable and otherwise, end badly indicate that there is a real problem for the community as a whole that needs to be addressed positively. I do not think that this suit is unjustified. The stated policy may be enlightened, but if it is, its execution in too many cases does not reflect this enlightenment.

I am white and lived in Boston for 37 years, during which time I witnessed several such unreasonable searches over the years, including one, in which an African American couple, all dressed in Sunday finery, were leaving a Morehouse College Glee Club concert–the husband was an alumnus,during which stop the 78-year old bourgeois couple were treated like felons-in-witing with no reason given for the stop. Other non-Caucasian friends and acquaintances–ordinary, law-abiding citizens–have told me of similar stops to me over the years, Given what has happened here over the past few years, I am convinced that such unjustified stops do occur here, and that African Americans and Latinos often have good reason to feel that they are being unfairly targeted to the point of harrassment.

Large organizations such as big city police departments, even those led by relatively enlightened chiefs and CEO’s, tend not to respond positively to complaints until compelled to recognize that it would not be in their interest to ignore them. This lawsuit is a means of getting the Milwaukee Police to do so.