The Curious Politics Of Rural Counties

New voting data shows their power, but makes their trust in Trump a mystery.

Donald Trump won the presidency by tapping into a sense of distress felt by people living in less-populated areas. This has a certain irony. Neither he nor his appointees has much in common with the people who put him in office. As is often noted, Trump may be the most urban candidate ever elected president. He has also stocked his administration with people who have gained great wealth from the very same economic changes that have hurt his rural supporters.

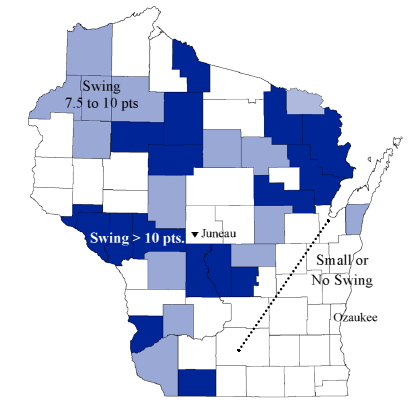

Trump won Wisconsin due to a shift in votes in places like Juneau County. Analysis from the Wisconsin Taxpayers Alliance helps make this point. WisTax ranked Wisconsin counties by the size of the swing from Barack Obama in 2012 to Trump in 2016 and created the map reproduced below. In counties shown in dark blue, Trump gained at least 10 percentage points compared to Mitt Romney. Counties shown in light blue had a pro-Trump swing of 7.5 points or more.

This level of volatility may strike Milwaukee area residents as strange, but that is because the swing skipped the Milwaukee area, mainly occurring in counties left of the dotted line. Locally, partisan bubbles are durable and growing stronger. Republican counties—largely the Milwaukee suburbs–are reliably Republican. Democratic counties—led by Dane and Milwaukee—continue Democratic.

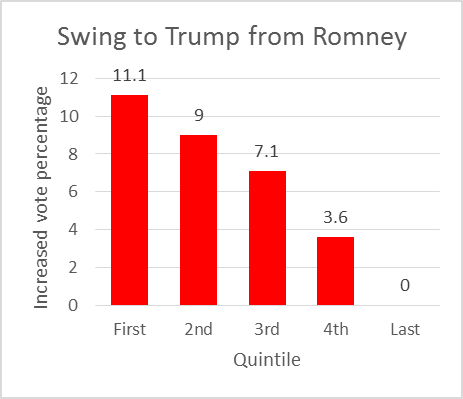

To help understand the Trump voters, WisTax divided the counties into five groups based on the magnitude of the swing from Obama to Trump. In the first group, the average swing was over 11 points, compared to no average swing in the fifth group. The next chart shows the average swing from Romney to Trump in each group.

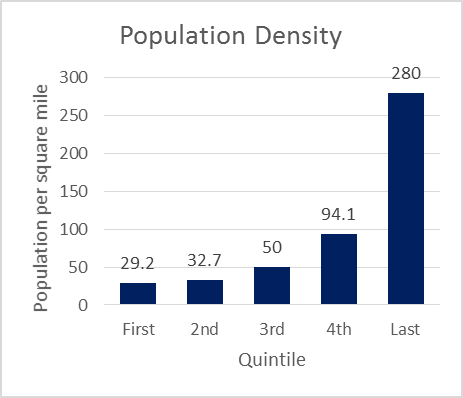

As the next graph shows, the counties with the largest swing had the smallest populations.

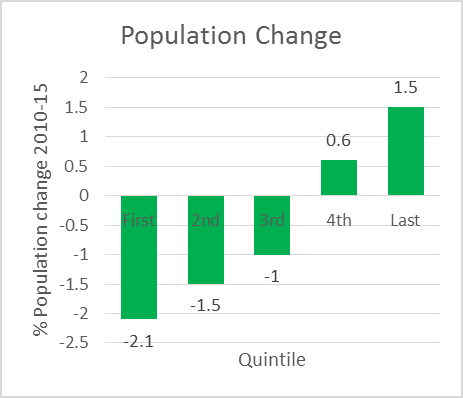

Not only did the Trump-swinging counties have the lowest population densities, but the population was continuing to shrink, as shown below.

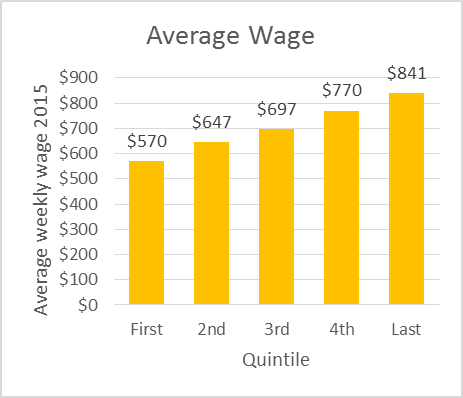

Finally average wages are lower in the counties with the largest swing to Trump.

These results are consistent with other findings both nationally and Wisconsin, some of which I described in an earlier column. Among Wisconsin counties, the stronger the swing from Obama to Trump the lower the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita. Nationally there was a much smaller number of counties voting for Hillary Clinton, but these counties accounted for 64 percent of the U.S. GDP.

In the past year, research has been published showing a decline in life expectancy among white Americans, particularly those without college degrees. The principal causes can be regarded as self-inflicted—alcohol, drug use, obesity, suicide. The Economist magazine recently made the connection explicitly by publishing a scatter plot showing a strong correlation between a weighted index of health outcomes (obesity, diabetes, heavy drinking, physical exercise and life expectancy) in counties to their shift to Trump.

In recent years, there has been growing research on inequality. In the words of a recent study by the economists Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman, those at the top have reaped most of the rewards of a growing economy:

Average pre-tax national income per adult has increased 60% since 1980, but we find that it has stagnated for the bottom 50% of the distribution at about $16,000 a year. The pre-tax income of the middle class—adults between the median and the 90th percentile—has grown 40% since 1980, faster than what tax and survey data suggest, due in particular to the rise of tax-exempt fringe benefits. Income has boomed at the top: in 1980, top 1% adults earned on average 27 times more than bottom 50% adults, while they earn 81 times more today. The upsurge of top incomes was first a labor income phenomenon but has mostly been a capital income phenomenon since 2000. The government has offset only a small fraction of the increase in inequality.

One lesson of the recent election is that inequality has a geographic component. While it certainly is a problem for large cities, growth has largely centered on big urban areas. Many people outside the cities feel left out. Trump’s success resulted from his recognition of this and his promise to solve the problem.

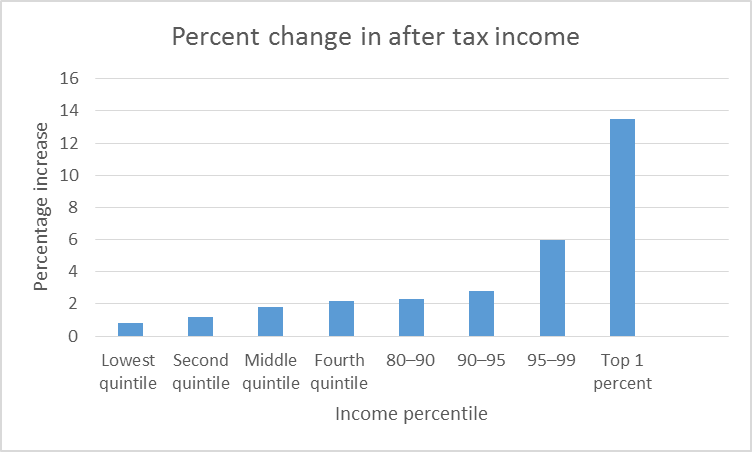

There are reasons to be skeptical about Trump’s ability—or desire—to reverse the fortunes of the people left behind. Take income taxes. Shortly before November’s election, Trump released a revised version of his plan to change the federal income tax. The proposal would cut tax rates at every income level, but by much more for the highest earners both as a percentage and in absolute dollar terms. The table below shows the effect on after-tax income calculated by the Tax Policy Center.

Standing alone, Trump’s tax proposal would make the federal tax system more regressive, meaning poor people would pay a larger percentage of their income than rich people. It would also create a huge new deficit. If the deficit were filled by cutting social welfare programs, such as Medicare, Social Security and Medicaid, the regressiveness would be still greater.

Thus, Trump’s most recent tax proposal would do far more for people in his tax bracket—and those of his cabinet picks—than for, say, the voters of Juneau County.

From a high-altitude viewpoint, what has befallen Juneau and other rural counties is an extension of a long-term trend. A 1981 article, entitled “Agricultural employment: has the decline ended?” reports:

In 1870, almost 50 percent of employed persons worked in agriculture and one farmworker could only supply five people with farm products. By 1980, just 4 percent of the employed were in agriculture, and each one supplied food for nearly 70 others.

As for the report’s question — has the decline ended? — we now know the answer is “No.” By 2012, agricultural employment had dropped to just 1.5 percent of American workers. The cause, of course, was not a collapse in demand for agricultural products. Rather, it was increased productivity: mechanization meant that fewer workers were needed. Towns built to serve the needs of farmers found the number of their customers declining.

A lucky few of these towns were able to attract manufacturers looking for a relatively cheap, but hardworking workforce. These towns grew into small cities, but their dependence on one or two employers left them especially vulnerable to the fortunes and whims of these companies. Also, as with agriculture, increased industrial productivity meant that manufacturing employment could decrease even as output increased.

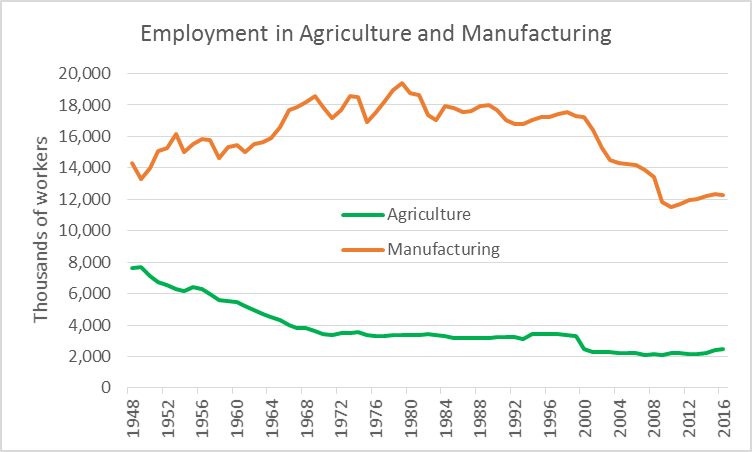

Here is a graph showing agricultural employment (green line) compared to manufacturing employment (orange line) since 1948:

As you can see, manufacturing employment has significantly declined since the late 1970s though it has rebounded a bit since the Great Recession. But agricultural employment steadily sunk from 1948 until 2000. Which makes the sudden emergence of rural and small city resentment towards large cities something of a mystery. The shrinkage in agricultural employment is long-standing. In fact, recently agricultural employment seems to have stabilized at a little over two million.

Part of the reason for the sudden prominence of rural decline in our political scene is likely Trump’s skill in picking up on the mood in the regions left behind, identifying supposed villains (China and Mexico) and claiming, without much detail, that he has a solution (re-writing trade pacts and keeping out immigrants).

The election shows that rural counties are in play and willing to switch their votes. This realization helps explain why Governor Scott Walker recently proposed to increase aid to rural school districts. Are Democrats able to come up with a plan that would actually help these areas?

Data Wonk

-

Life Expectancy in Wisconsin vs. Other States

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Republicans Opened the Door To Redistricting

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Connection Between Life Expectancy, Poverty and Partisanship

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Let’s just be clear what Walker is doing, he’s pandering to his perceived base. That if he showers them with money in this budget, these voters will think that somehow Walker won’t pull the rug out during the next budget.

Either way, the long-term effects of improving education in these truly rural areas will probably result in a greater outflow of people. Educated people have options and without a significant change in the rural business climate, even if a person prefers to live in their home rural area… they will move for work.

It’s still the right thing to do, Walker doing a good thing for bad reasons… even a broken clock is right twice a day.

If the real goal is economic development, then you need to focus on more than crops & animals as drivers of the economy. Those jobs are becoming more and more automated by the day, the owners are consolidating their operations which increases efficiency and lowers employment.

Jim Doyle, cue R weeping and gnashing of teeth, was pursuing a long-term program of import-substitution and growth in the manufacturing sector.

Why ship out rail cars full of money to buy coal, when a better answer is literally blowing in the wind?

Why do you think Doyle was pushing bio-generation facilities? Those efforts employ local workers long-term right here in WI and cannot be outsourced.

Import-substitution, product differentiation, growing up the value chain. These are the ways rural WI can grow and in turn help the rest of WI grow.

Thank you for this post and to Tim for his comment. As the November election and, before that, Prof. Kathy Cramer’s work show, different parts of the state seem to have great resentment toward each other. Much work would need to be done to address that resentment and to develop sound public policy initiatives, that voters in all parts of the state could support, to move the state forward. Unfortunately, that would require a mechanism for working together that does not seem to exist any longer.