Why the Estabrook Dam Was Created

Ancient geological conditions created troublesome stretch of the Milwaukee River which led to unique solution. Part 2 of a series.

The recently broadcast documentary “Milwaukee: A City Built on Water” makes a compelling case for the importance of water throughout Milwaukee’s history, and the value of studying and appreciating the historic context of the city’s current water initiatives. I think that the same is true for the Estabrook Dam and this section of the Milwaukee River. It’s important to know its unique history before forming a judgment about whether the dam should be removed — as a consensus of local leaders favor — or repaired, which I believe is the correct decision to make.

Geologic History of the Milwaukee River Near Lincoln Park

One of the more fascinating aspects of the study of geology is the occasional opportunity to make a connection between the landscape of today and geologic events that occurred millions or even hundreds of millions of years ago. Such is the case with this segment of the Milwaukee River, where during the Devonian geologic period (circa 360 to 420 million years ago), a limestone reef formed in a shallow sea due to some favorable combination of water depth, temperature and other conditions. Over time, thousands of feet of additional sediments were deposited, sea levels rose and fell, sediments turned to stone, and a reef was formed in this area (where the Estabrook Dam is located) which would influence the Milwaukee River.

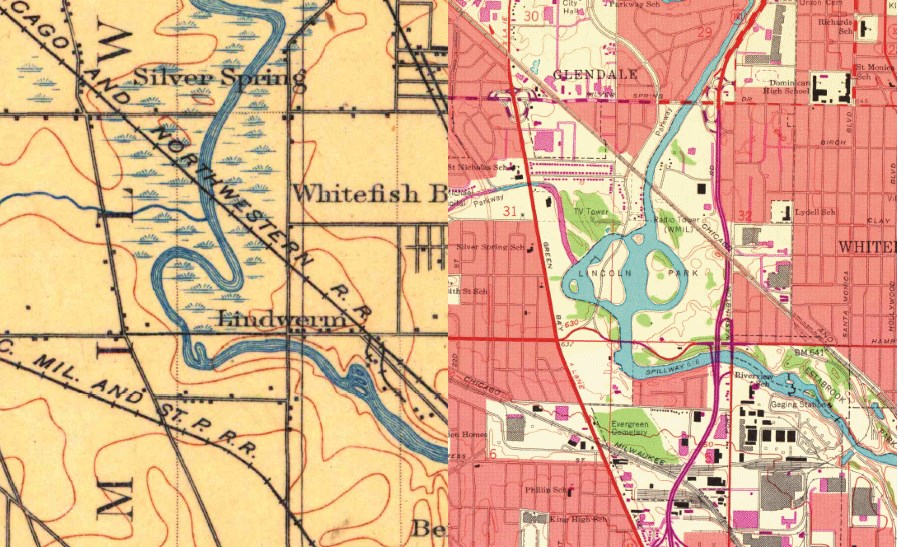

The path followed by the Milwaukee River was shaped in part by the retreat of glacial ice from the bed of Lake Michigan from approximately 14,000 to 9,000 years ago, and was described by William Alden, one of the most renowned glacial geologists in Wisconsin, as follows:

“Near Fredonia, when within 9 miles of [Lake Michigan]…it bends sharply to the right and flows southward, almost parallel to the lake shore, for more than 30 miles… its channel is within 3 miles of the lake shore, and at some points the shore is less than 1 mile distant.” That rather unusual course, he notes, is due to parallel ridges bordering the lake and the lack of any east-west valleys cutting through the ridges, which might have allowed the river to empty sooner into Lake Michigan. As a result, “the stream could find no other course than that to the south for a long distance” and not till it reached the Menomonee Valley “was the stream diverted to the lake.”

The Milwaukee River in the area of Lincoln Park reportedly occupies a former glacial outwash channel – thus its present location may actually predate the end of the Wisconsin glaciation, around 11,000 years ago. The progressive erosion in the channel of the lower six miles of the Milwaukee River was halted when the stream encountered the exposed bedrock formed by the ancient reef in Estabrook Park. Upstream from this barrier, the river developed a distinctly different geomorphic form – one characterized by a deep and meandering channel, surrounded by hundreds of acres of low lying wetlands prone to flooding. Below the reef, the Milwaukee River flows swiftly to its mouth at Lake Michigan.

Industrial Use and Transition to Recreational Use (1875-1916)

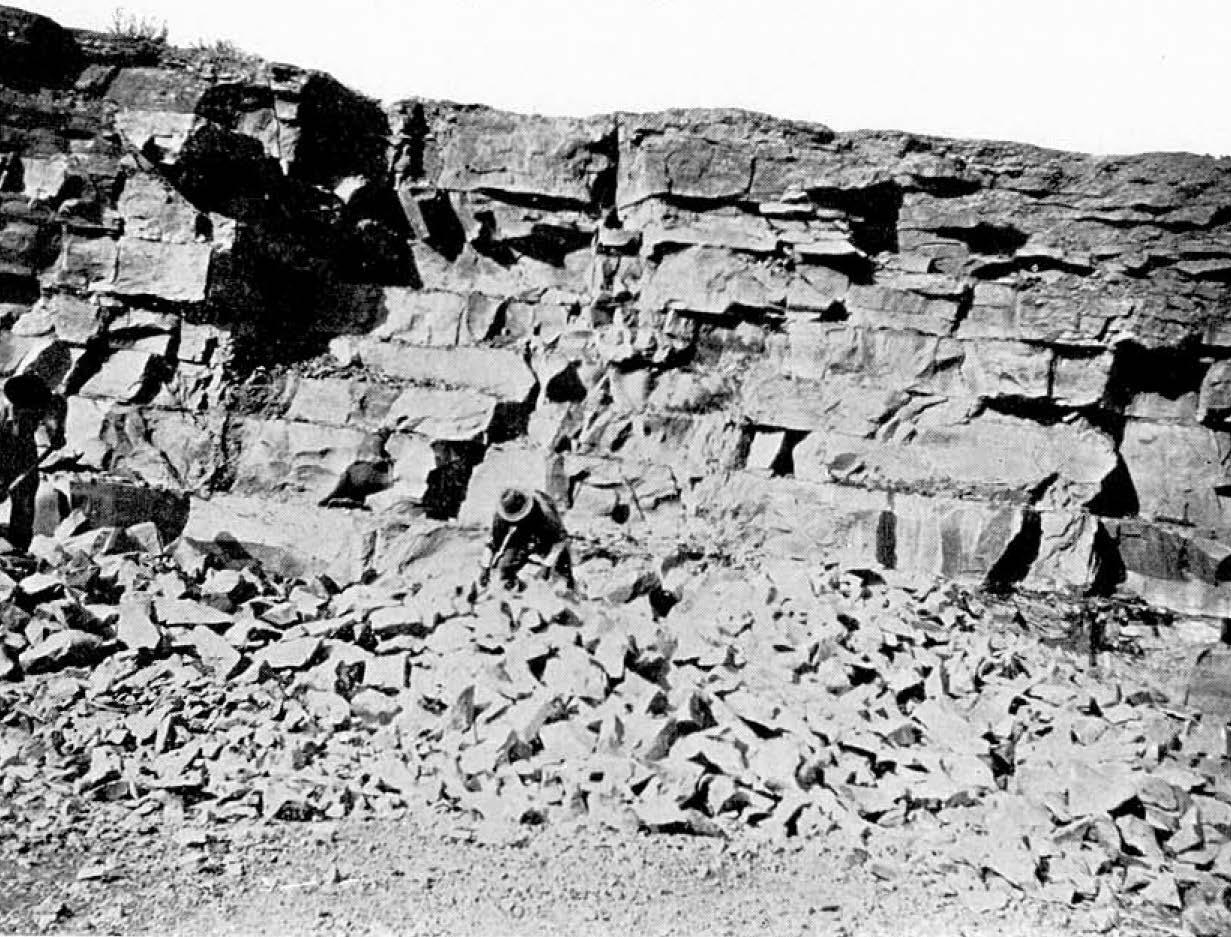

The exceptional chemical and physical properties of the bedrock in this segment of the Milwaukee River played a role in Milwaukee’s early industrial history. The Milwaukee Cement Company was established at this location in 1875-76, due to the presence of extensive bedrock outcrops associated with the ancient limestone reef. Its unusual chemical properties enabled the rock to be converted into an early type of high-quality “natural” cement.

The land occupied by the company and a competitor (the Cream City Cement Company) acquired in 1894 eventually expanded to encompass 350 acres of land that spanned both sides of a one-mile long section of the Milwaukee River extending from Port Washington Road to Capitol Drive. The industrial complex grew to include several large buildings, a network of rail spurs, extensive underground mines as well as quarries that occupied significant portions of the former bed of the Milwaukee River. By 1891, the company’s annual production of 475,000 “barrels” (each weighing about 265 pounds) made it the largest cement works in the United States and its products were distributed throughout a territory extending from Cleveland to Denver. However, the company’s supremacy was short-lived, as the invention of the rotary kiln enabled the production of the lower cost and higher quality Portland cement that remains in use today. By 1911, production was entirely suspended, and by 1914, the site was vacant, with the kilns dismantled and sold for scrap. As has been true in recent decades for so many other former industrial properties on the lower portion of the Milwaukee River, the closing of an outdated industrial facility turned out to be a necessary prerequisite for environmental transformation and renewal.

The transformation of this section of the Milwaukee River for recreational use was launched only two years later, when in June 1916, Milwaukee County purchased the portion of the former Milwaukee Cement Company property lying east of the river for construction of what was to become Estabrook Park.

Fossil collectors in the former quarry of the Milwaukee Cement Company on the south side of the Milwaukee River. (Source: Wisc. Geol. And Nat. History Survey Bulletin No. 21, 1911)

Flood Control and Depression Era Public Works Projects (1924-1940)

While the portion of the river east of Port Washington Road was dominated by industrial uses, upstream areas to the west were dominated by farming and recreation. The efforts to control flooding of the Milwaukee River in areas extending north through Lincoln Park, date back to at least 1924, the year of a major flood. The flooding problems in this area were a key factor in a series of public works projects completed over the next 15 years that included construction of the Estabrook Dam. The flooding was caused by several factors, but most notably two: (a) the approximately one-mile long limestone outcrop or ledge extending from 1000-feet east or downstream of the Port Washington Road Bridge to 4,000 feet upstream of the bridge and near the center of Lincoln Park, and (b) sharp bends in the River that slowed flow during the floods and which were susceptible to build up of ice floes during the spring thaw. As the characteristics of the limestone bedrock present near Estabrook Park had led to the development of the largest cement plant in the U.S., the erosion-resistant characteristics of the bedrock further upstream led to the flooding issues as well as to the extensive wetland complex covering an estimated 300 acres just upstream from the Estuary.

Use of the term “lake” for this section of the Milwaukee River as it existed prior to the flood control project is accurate, as it meets the definition of a “drainage lake” used by the Wisconsin DNR. To put this into perspective, the Milwaukee River drops approximately 750 feet in elevation (or 7.5 feet per mile) in the approximately 100-mile distance from its origin in Fond du Lac County to its mouth at the Lake Michigan, whereas there was essentially no drop in elevation for the 3 miles of the river that formed the drainage lake.

Landowners in the Lincoln Park area were actually instrumental in efforts to change state law related to flood control measures, in particular, a new chapter of Wisconsin Statutes (Chapter 79. Flood Control) enacted in 1931. Within a little over a month of enactment, the first petition under the new statute was filed with the Public Service Commission of Wisconsin by George Kramer (Secretary of the Lincoln Park Advancement Commission) and 48 others seeking relief from flooding by the Milwaukee River. The resulting Milwaukee River Flood Control Project initially focused on construction of a diversion channel near Thiensville to divert flood waters from the upper Milwaukee River directly into Lake Michigan. But technical challenges prevented this initial plan from moving forward, and less than two years later, in the fall of 1933, work on an alternative plan began, to remove the rock ledge and deepen the channel of the Milwaukee River and to build the dam.

Work on the channel deepening began as a Civilian Works Administration project. The channel modifications were described as having extended 1,600 feet downstream from the Port Washington Rd. bridge to 5,500 feet upstream, and as having created a channel with a uniform grade and a uniform channel bottom width of 200 feet. Although I haven’t found any engineering reports or articles documenting the original plans for the channel deepening project, the construction of a dam in Estabrook Park appears to have been a component of the overall project from its earliest phases. A layout plan for deepening of the channel within Estabrook Park dated December 1933, and approved by the Milwaukee County Park Commission in January 1934, included a dam, spillway, and ice breaker features at the approximate current locations, as well as channel modifications for the portion of the river extending from the Port Washington Road Bridge downstream to “Rock Ledge Falls” (about 1,300 feet downstream of the dam site).

Article Continues - Pages: 1 2

A Freshwater Controversy

-

The Path Forward for Estabrook Dam

Feb 10th, 2016 by David Holmes

Feb 10th, 2016 by David Holmes

-

Estabrook Dam’s Environmental Impact

![Photograph of fish passing through the fish passage at the Mequon-Thiensville Dam. As of June 2015, a total of 35-species of fish have been recorded by a “fishcam” in the act of swimming past the dam [http://www.co.ozaukee.wi.us/1248/Fishway-Camera]).](https://urbanmilwaukee.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/image03-185x122.jpg) Jan 17th, 2016 by David Holmes

Jan 17th, 2016 by David Holmes

-

Does the Estabrook Dam Cause Flooding?

Dec 30th, 2015 by David Holmes

Dec 30th, 2015 by David Holmes

Interesting article, but I still find myself focusing on:

The dam was created not as a boon to riverfront property owners, but as part of a decades-long effort to help transform a degraded industrial area into recreational parkways, to solve a major flooding problem, and to transform Lincoln Park into one the finest places for swimming, boating and skating not just in the county, but in the entire country. That history is critically important to understand in deciding the fate of the Estabrook Dam.

It never became “one the finest places for swimming, boating and skating not just in the county, but in the entire country” and the industrial area could and has been transformed without a real necessity for the dam. Additionally, I do not claim to be a flood expert, but my understanding is that the damn does not help alleviate flooding issues.

At this point, keeping the dam, because it seemed like a good idea 70 years seems like a waste of tax dollars and a mistake.

If we want to restore natural conditions to this section of the river, as this piece intimates, then why don’t we add rock fill back where the rock ledge was blasted out, and re-meander the river into the “s curve” it once was, get rid of the straight cut through Lincoln Park, and reestablish the wetlands that were once there? We’d be in favor of that, but there is no way it could be permitted. Keeping the dam does not restore natural conditions, not even close, and two wrongs don’t make a right. You could argue that the dam reestablishes higher water levels, but it does not reestablish natural flows or natural ecological processes that require a free river for fish passage, movement of sediment and organic material, freshwater mussel reproduction (which requires fish hosts to have free movement), etc. Keeping the dam does not address water quality problems caused by the dam or impacts to biological life (mussels, invertebrates, amphibians) from fluctuating water levels due to dam operations (fluctuating water levels due to gates being opened and closed). Lastly, although most dams were built for certain reasons, we need to examine whether it makes sense to keep these structures NOW based on new realities, which include major changes to water levels from upstream development and climate change, the increased risk of flooding caused by the dam NOW, as well as the high cost of fixing, operating and maintaining this 80 year old structure given the fiscal realities at the County (over $300 million+ in deferred maintenance needs for capital facilities). Dam repair with operations and maintenance is 3 times more expensive than dam removal (with fish passage construction and maintenance its likely closer to 4 times more expensive than removal). Over 300 homes could experience higher flood risks during any storms over the 5 year event if the County can’t get the gates open at a repaired dam, which has been a reoccurring problem in the past (due to poor condition, poor maintenance and electricity failures and lack of county resources). Regardless of the geologic history of this area, the County could and would be liable for that flood damage if they fail to act in a timely fashion. What the water levels were during glacial times is interesting, but increasingly irrelevant. I agree with Mike that keeping the dam because it seemed like a good idea over 80 years ago makes no sense. Removing the dam is the best alternative for the river and for the taxpayer NOW.

Wow, it was always a lake….built to preserve fishing and swimming. This is opposite of what Milwaukee Riverkeeper has always stated. Perhaps this is the reason Riverkeeper requested not to go to trial last summer…..over issues with the dam.

Dear Author, could you please list the sources and or methods you used to derive all of these complex calculations especially regarding: river miles (or feet), and changes in elevation?

How much would it cost to install a rock out crop that would raise water levels above the damn that would still allow some fish to battle over it compared to a traditional damn? Seems like that would be the best of both worlds.

Wonderful history.

But I am not sure what it has to do with the dam. Nature inexorably most forward, not back.

Cheryl Nenn says: “… why don’t we add rock fill back where the rock ledge was blasted out, and re-meander the river into the “s curve” it once was, get rid of the straight cut through Lincoln Park, and reestablish the wetlands that were once there? We’d be in favor of that, but there is no way it could be permitted. …”

That’s what many of us don’t understand: the “no way it could be permitted” part.

May as well get it out in the open. Even lefties (like me) need to know if the restoration option is hamstrung by, you know … those environmental … things.

To Casey and Gary–there was a rock ramp design to take out the dam structure and build essentially a ramp of rock. It couldn’t be placed where the old shelf was exactly, because models show that would increase water elevation, which is against FEMA rules. When placing a structure in the river or doing restoration, you need to show that you don’t increase water level by 0.01 inches. In the case of the dam, since its an existing structure, they don’t have to meet FEMA regs with a repair scenario. The reason we couldn’t put the ledge back in and/or re-meander the river is for the same reason that work was done in the first place–it would increase flooding of existing structures by causing an increase of elevation and backwatering effect. The river was modified to eliminate flooding. The dam was added on to the project because residents wanted to have their cake and eat it too–or namely, wanted to be able to drain the area to minimize flooding while also maintaining higher water levels for recreation and aesthetic reasons. I don’t dispute that the dam was put in place to re-establish the water elevation that was in the area. But from that information, one can not infer the river was deeper (there was a rock ledge) or wider. That is just not supported by the aerials, which we have going back to the mid 1800s. I have no idea where David is getting this “drainage lake” concept–its semantics. This area had a slowly meandering river that caused overbank flooding–that is what river bends/meanders do. Regardless of what we call it, there is not right to a water level, and upstream residents in favor of the dam can’t force a downstream owner to keep a dam if it is causing a nuisance or is a liability. There are hundreds of less vocal residents in the Lincoln Park neighborhood that want the dam removed to reduce flood risk. While the dam has changed the same over the last 80 years (albeit in a crumbling, deteriorated state), the water levels have not changed the same nor the increased rate of volatile storms. It is time for it to come out. Interestingly, the river seems to be favoring the west oxbow again post dredging. If we take out the dam, it may very well, re-meander itself. The east oxbow is becoming a wetland, with some assistance from local beavers. There is some hope that while we couldn’t go back to the way things were, that we may be able to approximate a more natural, free-flowing condition.

Above sentence should state “While the dam has STAYED the same over the last 80 years (albeit in a crumbling, deteriorated state), the water levels have not STAYED the same nor HAS the increased rate of volatile storms (WEIRD AUTOCORRECT).

I’d also add that the rock ramp alternative was in between the costs of repair and removal. About twice as expensive as dam removal. It would still be permitted as a dam, and maintenance would be required to ensure no increase in flooding upstream, etc. They were having a hard time designing a rock ramp that didn’t increase flooding. There was one design they looked at, which seemed buildable. As part of a fish passage, they will likely encounter similar issues. It’s not entirely clear how or where it would be built to not increase upstream water levels.

Milwaukee Riverkeeper had their chance for a day in court last July concerning Estabrook Dam but requested and was granted a stay. They did so because they lacked expert witnesses for their lawsuit against the county. Riverkeeper filed this lawsuit over 6 years ago, that was more than enough time to gather evidence involving the Dam.

I wrote a short article, “Milwaukee’s Lincoln Park District: A Look at Three Photomaps”, in Milwaukee History, vol 2, no 3, Autumn 1979. The article has three annotated aerial photographs: 1937 (shows the old meanders in Lincoln Park), 1954 (meanders removed via “straight-cut”, and 1971. I would appreciate the disclosure of the source of the older aerial photos (maps?) mentioned, going back to the 1800s.

I keep hearing the Riverkeepers state they want the river back to its natural state. Do they know how much this alternative would cost. You would have to repair countless shorelines that people live on not to mention digging out the impoundment area so the river was actually deep enough to have any chance to use recreationally. None of the “tear the dam down” advocates have this cost in any of their estimates if the dam was removed. They think they can tear the dam down and let nature take its course. They don’t care about the people that have homes on the river or the countless people that use to enjoy Lincoln Park. This area of the dam has been modified, and homes have been built since the dam was put in place. You cant just rip the dam out and say see you later. Riverkeeper is missing the big picture!!

Give it up Cheryl. You lost. Put your excellent mind elsewhere .

A before image of the river inserted into image of same location after Scott Walker stopped funding repairs on the Dam. https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10208244211043193&set=p.10208244211043193&type=3&theater

Thanks to everyone for the feedback.(including critical comments). One goal for the article series was to foster further meaningful discussion, in particular on some aspects of the controversy that seem to have received no attention to date. My work and travel schedule this week prevented me from responding earlier to some of the comments. Following are some initial responses to a few of the comments.

Regarding comment 1 by Mike C: I believe the extent to which Lincoln Park achieved the vision of becoming “one of the finest places for swimming, boating and skating in the country” is subject to debate. In fact, it may have come close to achieving this vision in the 1940s before increasing pollution in the Milwaukee River associated with Milwaukee’s expanding industrial footprint and urban sprawl led to the closure of the swimming beaches at Lincoln and Estabrook Park. Previous discussions seem to have missed the point that Lincoln Park was specifically designed to provide water-based recreational opportunities associated with the impoundment. I think that the vision for Lincoln Park from 70 years ago is in fact completely relevant to the recreational needs of residents living today in the neighborhoods surrounding Lincoln Park. I remain unconvinced that removing the dam will simply replace one type of recreational opportunity with another of equal value.

Regarding comment 4 by A. Nonymous: I don’t have a technical reference, but those statistics were presented in the introduction to the “River Reborn” article series in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel which can be found here: http://www.jsonline.com/news/milwaukee/5-billion-revival-leaves-milwaukee-river-cleaner-more-valuable-b9948752z1-261880681.html

Regarding comment 6 by Tom Bamberger: I disagree. I think understanding the historic significance and context is an essential element of any decision affecting a major public resource. This context has been missing from most previous discussions of the dam, and the impoundment has been characterized (at least initially) as an artificial feature in existence for a few decades. Context has generally been lacking as well the significance of the dam and impoundment in the development of Lincoln Park. The impoundment wasn’t a feature that just happened to be located in Lincoln Park. It was the key element of the Park. Considering the historical context is an essential element of moving forward in a manner that will provide greatest lasting benefit.

Regarding comment 8 by Cheryl Nenn: The drainage lake concept is from the WDNR. The description of a deep swimmable pool existing upstream from the high point of the rock ledge is from engineering documents of the 1930s, as referenced in the article. As a geologist, I found the description of this deep pool upstream from the high point of the rock ledge somewhat curious. It’s possible that it could have formed due to flow dynamics and erosion acting over the past 10,000 years. I suspect it might have formed at towards the end of the Wisconsin glaciation when the pre-cursor to the Milwaukee River may have at times served as a major outlet for glacial meltwater, with flows that at times could have been vastly greater than peak flows occurring during recent millennia, and flows ladden with boulders and glacial detritus that can erode rock at a much greater rate.

I’ll try to post one or two more comments over the weekend.