Why Estabrook Dam Must Be Saved

Removing it could cost more, damage environment and foreclose innovative solutions. First in a series.

Over the past year, the Estabrook Dam has been in the news with increasing frequency. The aging dam owned by Milwaukee County is under repair orders from the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and is subject to both a lawsuit and ongoing controversy regarding its future. A broad consensus favors removing the dam, including Milwaukee County Executive Chris Abele, environmental groups, the Milwaukee Common Council, Shorewood Village Board and Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District (MMSD). The majority of county residents support dam removal, county supervisor Patricia Jursik has said.

Meanwhile, repair of the dam is favored primarily by a group of riverfront homeowners who stand to lose access to the three-mile impoundment — a kind of mini-lake formed upstream of the dam (at least until 2008, when the gates of the dam were opened in response to a DNR order, drawing down the impoundment). These homeowners have been supported by county board chair Theo Lipscomb, who lives in the area and has used parliamentary maneuvers to prevent the board from voting up or down on the issue of removing the dam. (The board voted to create a fish passage around the dam, and last week voted to override a veto of this by Abele.)

But could the consensus against repairing the dam be wrong?

Having been significantly involved in previous efforts to remove dams on the Milwaukee River (including helping to secure the funding used to remove the Lime Kiln, Newburg, and Campbellsport Millpond Dams), I am familiar not only with the compelling arguments in favor of dam removal, but also the sometimes questionable (or highly self-interested) claims used by those in opposition to removal. Motivated in part by my previous series for Urban Milwaukee on Milwaukee’s freshwater landscape, I decided to take a closer look at the debate on the Estabrook dam. I was surprised to discover not only a remarkable history for this segment of the Milwaukee River, but also to find that many of the technical arguments in support of removal do not hold water, pun intended. In addition, I am convinced the decision to remove or repair the dam is relevant to Milwaukee’s growing identity as a water technology hub. In short, this is a very important issue.

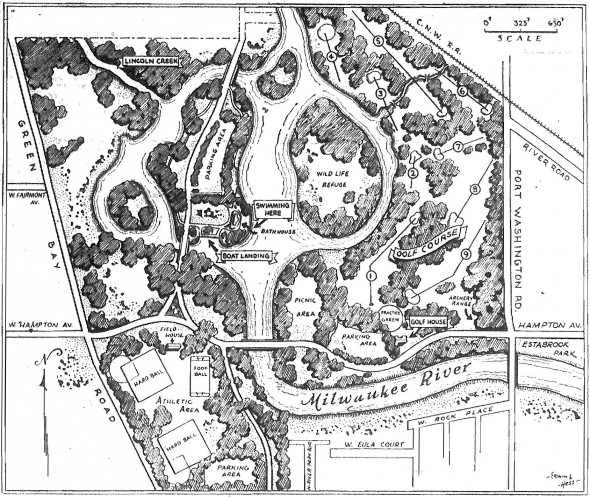

The design and construction of the dam occurred over an eight-year period from about 1932-40, in what could be described as an early water initiative focusing on this section of the Milwaukee River that included the development of both Lincoln and Estabrook parks. Comparing this earlier effort to Milwaukee’s recent water initiatives, it’s hard not to be impressed by its scope and accomplishments. The earlier initiative was the result of a decades-long collaboration between the City of Milwaukee, Milwaukee County, and multiple federal agencies, with stated goals not only of reducing flooding and enhancing recreational use of the river, but also preserving a unique hydrologic feature – a drainage lake that appears to have existed in the area of Lincoln Park since before the end of the Wisconsin glaciation.

Much of this work was done during the Great Depression and included a grand ambition – to create a public water-focused amenity in Lincoln Park that would be unmatched by any city in America in its combination of swimming, recreational boating, and ice-skating amenities. As is the case with Milwaukee’s current water initiative, this earlier effort included collaboration by the county and city with the university system (the hydraulics lab at UW‐Madison) which led to use of an innovative design for the spillway that combined beauty with greatly increased hydraulic capacity. Whereas over $5 billion has been invested in recent decades for the stated purpose of making Milwaukee’s rivers “swimmable and fishable,” this goal was shared by the earlier initiative – which included preservation of the natural drainage lake that existed prior to the dam (through the construction of the dam which crested at the exact same elevation as a bedrock ledge removed for the flood control project), and through the construction of public beaches for swimming facilities at both Lincoln and Estabrook Park. The original design for the dam included construction of a fish passage (though it’s unclear whether this was constructed, removed at a later date, or ineffective). The dam has been described as obsolete, but the process and vision that guided its construction would appear to be in tune with that driving Milwaukee’s current water initiatives.

Some other key findings related to the dam as I now understand them, include:

Relative Costs: The impact of dam removal on adjoining property values (and associated property tax revenues) will likely be far greater than estimated in either the environmental assessment prepared for the dam, or in materials published by Milwaukee Riverkeeper or other advocates for removal. At the Mequon-Thiensville Dam – the nearest upstream dam on the Milwaukee River with a boatable impoundment – riverfront lots upstream from the dam (with access to the impoundment) are valued at approximately $74,000 per acre more than lots below the dam on the same street, and same neighborhood, but lacking access to an impoundment. If the impact on property values and property tax revenues is included in cost analyses, the cost for removal of the Estabrook Dam may actually be substantially higher than costs cited for repair and maintenance.

Environmental Benefits: The environmental benefits attributed to removal of the dam (reduced sediment accumulation, enhanced fish populations, general improvements in water quality) appear to be unsubstantiated by either actual data collected from this section of the Milwaukee River or by data collected from comparable rivers and dam removal projects. In terms of sediment accumulation, based on the storage capacity of the impoundment relative to the mean average annual flow volume of the Milwaukee River, the “sediment trap efficiency” of the impoundment should be nearly zero. In short, little or no sediment collects in the impoundment (beyond that associated with flow in other segments of the river). Not only are the environmental benefits largely unsubstantiated, but removal of the dam has the potential to result in negative environmental impacts to this segment of the river, given its unique hydrologic conditions – in part associated with the flood control project undertaken as part of that Great Depression water initiative, which excavated an approximate 7,000-foot long, 200-foot wide, and five-foot deep bedrock channel within which flow of the river is restricted in areas directly upstream from the dam site.

In spite of claims to the contrary, removal of the dam would almost certainly have significant negative impacts on recreational values within the three mile segment of the river impounded by the dam, as well as troubling environmental justice implications:

- Use of the impoundment for recreational boating will be permanently eliminated (an outcome that should not be taken lightly given that the impoundment appears to represent the only boat-able inland lake in Milwaukee County).

- Use of this segment of river for kayaking and other paddle sports is likely to be significantly reduced due to the shallower water and/or higher flow velocities.

- The recreational value of Lincoln Park will be negatively impacted, given that it is a park specifically designed for water-based recreational activities (swimming, boating, and ice-skating).

- Removal of the dam could have the unintended but enormously important result of eliminating the possibility of achieving swimmable rivers (regardless of future improvements in water quality), as the impoundment may represent the only remaining location in Milwaukee County where physical conditions suitable for safe swimming are present in a river.

- Though this segment of the Milwaukee River appears to have the highest percentage of African American residents in adjoining census tracts of any major waterfront area in the state, there appears to have been no meaningful participation by these residents in any of the public outreach or the decision process to date. A decision to remove the dam under these circumstances would have extraordinarily negative environmental justice implications, as there is no evidence that creating a “free flowing” and “more natural” river with greatly reduced recreational opportunities would serve the interest of these residents.

Perhaps the most important factor to weigh in evaluating repair versus removal is that a decision to remove the dam will be permanent. There will be no possibility of constructing a new dam at some future date, if a determination is later made that the environmental or flood reduction benefits were negligible, and the loss in property values, property tax revenues, and recreational uses were much greater than assumed. The option to remove the dam will always be a possibility, and a decision that could be made at some future date once there are better data available to document the negative environmental impact of the repaired dam (if any), the flood impacts (if any), and the preferences of residents in neighborhoods that should be included in any future evaluation process.

Flooding of rivers is a major global water challenge, and one that is projected to grow significantly over the next 15 years. A study published earlier this year predicted that the global risks associated with flooding of rivers would triple over the next 15 years, with the associated annual costs (converted to dollars) from flood damage rising from about $102 billion to around $534 billion. The challenge of designing engineered systems to alleviate flooding while trying to minimize the negative environmental impacts is a global water challenge to which the Estabrook Dam is relevant.

The challenges associated with the dam’s repair would appear well suited to innovations in systems to guard against power failure, to improve automation of the gates and to provide “real‐time” control in response to rapidly changing flow conditions during a storm event, and design of a fish passage that could enhance recreational opportunities as well as to reduce upstream flood levels. The possibility for this type of innovation to occur in Milwaukee seems quite plausible given its status as a leading global center for industrial controls (Rockwell Automation), advanced batteries (Johnson Controls), emergency power systems (Generac and Kohler Power Systems), and use of real‐time control systems for managing the flow of stormwater (MMSD). While it is nice that a water theme — a wavelike form — has been reportedly integrated into the design of the proposed Milwaukee Bucks arena, and that water features are being incorporated into the streetscape as part of design of the Lakefront Gateway Project, the Estabrook Dam would appear to represent a far more relevant canvas for demonstrating Milwaukee’s water‐related innovations and the budding water hub’s ability to design engineered systems to alleviate flooding while minimizing negative environmental impacts. It could be a wonderful test case of Milwaukee’s ability to be a leader in water technology solutions.

Abele is a great believer in basing policy decisions on best practices and financial efficiency, and has argued that removal of the dam would be “most environmentally friendly and fiscally responsible option.” That contention, though widely shared in the community, strikes me as dead wrong. With that in mind, this series will examine the saga of the dam in detail, beginning with a history of the segment of the Milwaukee River that includes the dam, followed by an analysis of key arguments related to costs, flood impacts, and environmental impacts or benefits. This will be followed by an analysis of recreational uses, the goal of swimmable rivers, and environmental justice considerations. The series will conclude with an assessment of the dam decision process in the context of the Milwaukee water hub initiative, with suggestions for an alternative path to pursue.

A Freshwater Controversy

-

The Path Forward for Estabrook Dam

Feb 10th, 2016 by David Holmes

Feb 10th, 2016 by David Holmes

-

Estabrook Dam’s Environmental Impact

![Photograph of fish passing through the fish passage at the Mequon-Thiensville Dam. As of June 2015, a total of 35-species of fish have been recorded by a “fishcam” in the act of swimming past the dam [http://www.co.ozaukee.wi.us/1248/Fishway-Camera]).](https://urbanmilwaukee.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/image03-185x122.jpg) Jan 17th, 2016 by David Holmes

Jan 17th, 2016 by David Holmes

-

Does the Estabrook Dam Cause Flooding?

Dec 30th, 2015 by David Holmes

Dec 30th, 2015 by David Holmes

Nonsense! All of your arguments are specious. Returning the river to its natural state is logical and humane. Just tear it out.

Finally we’re getting an article, from a credible source, that will provide parts of the story that were denied by the administration for years. Previously, the other media seemed to gravitate to the “experts” from the county and Riverkeeper who, regardless of the truth, were on a mission to remove the only boatable lake in Milwaukee County. Milwaukee County Executives and their appointed department heads have bought and paid for bad science to support their mission to remove this dam.

The Milwaukee County Board of Supervisors are heroes for not buckling under pressure and saving the county millions in this matter!

Thank you Urban Milwaukee for telling this story.

Trying to engineer our rivers was one of the great ecological catastrophes of the 20th century. There is no better design than nature’s design, and the best flood control comes from leaving an undeveloped buffer strip alongside a river’s banks to absorb floodwaters. As for recreational opportunities, the author is off base. Stagnant impoundments are neither safe nor pleasant places to swim. Anyone who canoed upstream of the dam before the gates were raised can attest that the water was foul-smelling, trash-filled, and generally disgusting. I won’t deny that this debate could stand to be more inclusive. Among those who will never be polled are the voiceless wild creatures calling the Milwaukee River corridor home. As a biologist, I can assure you that this will be a healthier ecosystem and a better habitat for wildlife with the dam removed and the river flowing freely.

I’ve advocated for the dam removal based on the available information out there. This is new information and presents possible legitimate reasons to find an alternative solution. I look forward to rest of the series.

As of right now, I still think Lipscomb based his dam-saving maneuvers on protecting a few landowners property rights over the interests of the county as a whole.

Just some non-specious facts from a “humane” river user.

Environmental groups stated, “Removal of the dam could improve recreational fishing opportunities upstream and downstream of the dam,” for those fishing primarily for salmon, and trout. When the Lincoln Park lagoon existed I can truthfully state that, during my paddles up and down the Estabrook Impoundment Area, I have caught fish and gazed upon wild life.

Fish = Bluegills, Sunfish, Catfish, Bullheads, Northerns, Bass, varieties of minnows and of course Carp. These lured lots of inner city fishermen with cane pulls and inexpensive rods and reels. Trout and Salmon were always there during their runs and attracted the fly fisherman a couple months out of the year.

Wildlife = Crayfish, River Clams, Western and Midland Painted Turtles, Common Snapping Turtle, Banded Kingfisher, Green Heron, Night Heron, Great Blue Heron, Egrets, Mallards, Wood Ducks, Mergansers, Coots, Red Tail Hawks, Coopers Hawk, Sharp Shanked,Great Horned Owls, and of course Canadian. Coyote, Dark Mink, Musk Rat, varieties of Frogs, Possum, Deer and Raccoons.

What has disappeared from the river since the gates have remained open is the Boys and Girls clubs that taught canoeing skills from the Kletzch dam down to the Estabrook. To remove the dam will insure that this section of the Milwaukee River will remain shallow and non-navigable for anyone paddling in a normal sized canoe. It would also eliminate the pond ecosystem and replace it with a fast flowing river which a comparatively few fly fisherman wish to enjoy two months out of the year.

A multiuse urban recreational waterway is what a thriving urban city needs for its citizens, not an imagined wild river that fly fisherman in waders, waddle a dozen yards from their parked pickups and SUVs to practice their casts.

I also am a big proponent of environmental justice & would like to bring back the opportunity for poor neighbors to watch people ride around on their boats.

Next we’ll talk about opening a polo field in King Park near 17th/Vliet right?

This is the stuff that shows the Milwaukee county board is a bunch of free-spending, useless political hacks.

Tim, your comparison to having water activities readily available to lower income areas is not at all comparable to horse ownership and extremely short sighted… who are you to say the residents in the area can’t afford or are not good enough to enjoy water sports and recreation?

The lake area formed by the dam is a natural amenity (yes, natural… this dam replaced a natural rock formation that created a lake long before the dam was built to control flood waters) that should be cherished and made clean and whole again. We can’t just focus on our downtown and making just that one part of the city attractive for people to use for recreation.

We just spent a ton of money cleaning up the sediment in Lincoln Park left over from an era of dirty industry. Let’s continue that work to make this a thriving area that Milwaukee can be proud of and used by people of all different incomes and backgrounds. It takes someone with vision to realize this can benefit more than a few people who live along the shoreline.

Good for David Holmes and UM for wading into these murky waters. I look forward to reading the full series and having new perspectives to consider.

I thank Mr Holmes for researching and writing this article and for Urban Milwaukee for publishing it. For too long only items that would favor removal of the dam were brought to light and items that would favor repair and restoration of the dam were suppressed. Information has been manipulated to favor only one side of the issue. It looks like we will now get amore unbiased look at all of the issues.

Millions and millions have been spent removing the PCB’s from the Lincoln Park Lake. It would be a travesty to remove this lake from the community that uses Lincoln Park. There used to be signs warning the users of the park of the PCB dangers. Those signs are now gone.

Tons of logs, trees and debris are removed in front of the dam. With out the dam all of those logs, trees and debris would end up downtown in the river walk area to be dealt with there. Anyone ever mention that.

I look forward to reading the rest of Mr Holmes article.

I’m puzzled as to the reasoning behind the claim that removing the dam is permanent while building one leaves options open. Why wouldn’t some future generation be able to build a new dam if they so desired?

I’m glad to see Dave Holmes active again. Keep the dam!

Good article, I’m glad to see someone speak up for the residents and bring perspective to the discussion. We shouldn’t sacrifice the neighborhood and its amenities for another neighborhoods enjoyment.

David Holmes, thank you so much for putting forth your extensive expertise to guide a controversy that has been too long on ideology from Riverkeeper and lacked perspective about upstream property owners who are invested in the river and basin as it has been for decades. This is information for all. Note: the funds for the fish passage have been allocated. Thank you for your ecological and social policy wisdom.

I am responding to the comment David Cole posted, in which he said “Trying to engineer our rivers was one of the great ecological catastrophes of the 20th century.” I agree with that statement but also believe that most people, including Mr. Cole just don’t understand that the Estabrook Dam restores the most natural state the river could be restored to at this time. I’ll explain:

In the mid 1930s, the Civil Works Administration, Public Service Commission of Wisconsin, and Wisconsin State Planning Board, who were administering the flood control project in the area found out that it was a terrible idea to disrupt the natural historic water level and that, as Mr. Cole said, “there is no better design than nature’s design”. The flood control project had removed more than a lineal mile of limestone out of the riverbed, lowering the natural water level by almost eight feet by 1935. Changing the shoreline, habitat and losing the natural lake were unintended results. Locals threatened to sue over their loss and the government realized the locals would easily win water rights lawsuits. On April 19th, 1937, the Department of Interior released a new plan to retain the natural historic water elevation while protecting the area from flood hazards; they would build a dam that would return the river to the same level as before the rock ledge was removed. This is all documented in several historic documents including “Department of the Interior, National Parks Service, Project SP-5 Job No. E. C. W. 123, Proposed Dam, Estabrook Park, Milwaukee County”, “Public Service Commission of Wisconsin Document, regarding Milwaukee County Dam Permit Application) 2-WP-142”, and “Civil Works Administration, City of Milwaukee. Removal of Rock Ledge, Project Summary and progress report, April 23, 1934”

As I’ve already established, the Estabrook Dam does not cause an artificial impoundment but rather restores a natural lake. Rivers and lakes often go together. Most Wisconsin rivers naturally include a variety of riverine environments including areas of still water, and consequently accommodate a greater diversity of life. Milwaukee River has at least 4 other natural lakes including Mauthe Lake, and Long Lake in Kettle Moraine State Park. Would Mr. Cole like those lakes removed as well? With the goal of swimmable, fishable rivers, we paid more than $50 million tax dollars to clean up the Milwaukee River and its tributaries. Why would we want to drain the river to the point that swimming is no longer possible? With over 30 other dams on the Milwaukee River and over 1100 other dams in the state, why would we drain the only boatable inland lake in the most populated county of the state?

In his comment, GB James asked “Why wouldn’t some future generation be able to build a new dam if they so desired?” My response is that a future dam would be nearly impossible in our current legal climate. Wisconsin is one of the most aggressive states in removing dams and regardless of the situation or results, our DNR will try to remove every dam possible. Estabrook Dam must be saved.

D. Cole wrote: “Trying to engineer our rivers was one of the great ecological catastrophes of the 20th century. There is no better design than nature’s design …”

I haven’t rechecked all of the recent discussion on the issue, but an argument for the compromise of replacing the original rock shelf with some engineered version is a little hard to find in official versions. There must be a reason for that – too logical?

A replacement of the original “shelf” would clearly retain some of the water level and help improve the flow. A modest portage for canoers & kayackers shouldn’t be a hardship – apparently it wasn’t a problem for historic fish populations?

Gary wrote: “A replacement of the original “shelf” would clearly retain some of the water level and help improve the flow. A modest portage for canoers & kayackers shouldn’t be a hardship – apparently it wasn’t a problem for historic fish populations?”

It would seem a shelf would be a good compromise.

One important part of this debate that is often glossed over is 120 years of Wisconsin water law. Property owners who have access to the river either because it is their back yard or there is a community boat launch that they have access as part of their deed have a protected right to the original water depth of the lake. That right was reaffirmed by the State Supreme Court as recently as 2013. Also, the Lincoln Park boating amenities were designed to utilize the original water depth. The home owners’ prospective is that the final proposal needs to retain the original natural water depth during the summer and fall. A shelf that high would be rebuilding the original structure which was considered unsustainable back in 1929.

The environmental groups opposing repairing the dam are opposed to any dam. That leaves very little room for negotiation.

In the past I’ve enjoyed canoeing the river north of the dam, especially the Lincoln park areas, as I’ve enjoyed canoeing various other cities semi urban waterways. I’d hate to lose and would in fact appreciate an enhanced, canoeable improvement to this area . I had thought the issue was simply above-dam home owners vs clean river proponents. After reading this article I’ve changed my view from pro dam removal to now neutral on the subject. Let the debate continue!

Thanks to all for your comments. Regarding comment #10, my statement that the dam could never be rebuilt at a later date may merit further explanation. My assumption is that in order for a permit for a new dam to be approved, the dam would need to be designed in a way such that there would be no increase at any upstream location in the 100 year flood elevations. Modelling by SEWRPC of flood levels for various Estabrook Dam repair, replacement, or removal alternatives indicate that removal of the current dam would lower the 100-year flood elevations by up to 1.5 feet. A new dam would be restricted to these new lower flood levels.

As further explained in the modelling report by SEWRPC: “Chapter NR 116, “Wisconsin’s Floodplain Management Program,” of the Wisconsin Administrative Code that do not permit activities which would increase the 1-percent annual-probability flood stage unless easements were obtained from all affected property owners and a Conditional Letter of Map Revision (CLOMR) were obtained from FEMA prior to any construction.” “As part of a CLOMR application to FEMA it would be necessary to 1) prepare an analysis of alternatives to the proposed project, 2) obtain documentation that all affected municipalities concur with the proposed floodplain changes, 3) provide assurance that no insurable structures are affected by any changes in the 1-percent-probability flood profile, and 4) notify all property owners affected by the changes in the 1-percent-probability flood profile.”

Other environmental requirements would apply as well. My assumption is that these requirements would be impossible to meet for any future dam at this location.

I’m on the board of a non-profit that worked to try to keep a former Girl Scout camp open. Things went a different direction and the citizens of the local community voted for a levy that provided funds to purchase and repair the camp. The camp has two lakes and the lower lake was patented by James Kirby (vacuum cleaner fame) and was used to run his hydro-electric power Millwheel. Long story short after helping the levy pass, the overseers of the land brought in experts who are recommending the lower lake’s dam be removed, along with our group’s dream to restore the Mill as an homage to Kirby, history of the area and to show students what can be done

They all say the same things but there must be some experts that have knowledge that could help us. Any thoughts?.