Closing of MU’s Neighborhood Health Center Lamented

Marquette-run, near north side center had 500 clients, many struggling to find health care.

Quanisha Shadd holds a bag of ice during a Centering Pregnancy exercise about dealing with labor pain. Photo by Devi Shastri.

It is late morning at the Marquette Neighborhood Health Center when seven pregnant women arrive. They measure their weight and blood pressure, meet with a midwife to hear their child’s heartbeat and sit in a circle to discuss their pregnancies. For these women, the center is more than a place to get basic healthcare — it is a place of support.

“This is my third (child) … and I’m still nervous,” said expectant mother Tamieka Bratton. “It just was nice knowing that somebody else was in that same situation,” referring to the other participants in the health center’s Centering Pregnancy program.

Bratton is one of many searching for a new provider following the Marquette College of Nursing’s decision to close the clinic on July 10, which came as a surprise to the nurses and patients. They were notified of the pending closure five weeks ago.

“We did think that we had at least another year, as our federal HRSA (Health Resources and Services Administration) grant was originally scheduled to end in June of 2016,” said case manager Heather Saucedo. “So the news of the clinic’s closure came as quite a shock to me.”

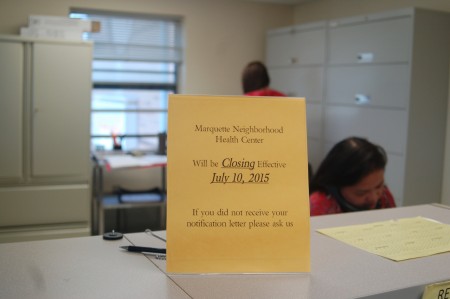

The Marquette Neighborhood Health Center announced five weeks ago that it would close on July 10. Photo by Devi Shastri.

The clinic, which is open five days a week, had been struggling financially for a few years. About 85 percent of its patients are on Medicaid.

The nurse-run health center opened in 2007 when Marquette bought out a private practice. It was initially located just outside the university campus and provided primary care for Marquette community and surrounding neighborhoods. Following the award of a five-year $1.5 million grant from HRSA in September 2011, the clinic began offering midwifery services and focusing exclusively on women’s healthcare.

The goal was to reduce Milwaukee’s high infant mortality rate, especially for African-American women. The center moved off campus to its current location in the Hillside Family Resource Center, 1452 N. 7th St., to be more accessible to its target population.

However, as the center completed the fourth year of the grant, the practice was struggling to find patients.

“The HRSA grant is one that decreased annually over its five-year span, requiring the College of Nursing to subsidize the clinic with additional revenue,” said Brian Dorrington, senior director of university communication at Marquette. “With a continued reduction in patient visits, this model was no longer sustainable and it wouldn’t have been prudent to continue accepting grant funding.”

In March, the clinic reported that 98 percent of its pregnant patients reached full-term – 10.5 points above the national average.

“At a time where (midwives) are … working so hard to improve infant mortality and health outcomes of infants and mothers, it’s a tremendous loss,” said Bev Zabler, the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee College of Nursing’s assistant dean for practice and partnership. “(MNHC’s model) needs to be looked at and possibly replicated.”

Patients feel abandoned

The clinic’s patients are reeling from the decision. There were about 500 clients at the time of the decision to close.

In addition to pregnancy care, the clinic provides primary care, runs laboratory tests, and treats minor injuries and infections. It is open five days a week from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m.

MNHC’s Centering Pregnancy program, a support and education group for pregnant women, disbanded half way through a 10-session course meant to last the duration of the pregnancies. According to Saucedo, the clinic is one of only four certified to offer the program in Milwaukee, leaving many searching for alternatives as their due date nears.

“They didn’t even extend (the closing date) until at least all of the Centering was done, which is sad,” said Leosha Stones, who is 31 weeks pregnant. “You’re affecting a community. You’re taking these things that are beneficial to the community away.”

Dorrington explained that the decision to close in five weeks was made to “coincide with the end of the HRSA grant schedule, as well as the end of the college’s facility lease with the City of Milwaukee.”

Stones said that the result is an unnecessary health risk for the patients.

Tamieka Bratton listens as lactation consultant Angela Lang speaks to her Centering Pregnancy group at the Marquette Neighborhood Health Center. Photo by Devi Shastri.

“A lot of us are midway through our pregnancies and now we have to discomfort ourselves by trying to find another practitioner,” she said. “It’s stressful for the people that are still pregnant and (they) are at risk for preterm labor.”

The leading cause, by far, of infant mortality is complications from pre-term birth, which can be triggered by stress, according to Milwaukee Commissioner of Health Bevan Baker.

Nurse-midwives at the clinic are referring patients to other midwives and healthcare providers to help reduce that stress. Dorrington also said patients were informed that they could go to two of the College of Nursing’s other clinics, which run in partnership with the Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin at the Northside YMCA, 1350 W. North Ave., and the COA Goldin Center, 2320 W. Burleigh St. Both clinics offer primary care services but not prenatal care or midwifery services.

Still, Stones emphasized that the relationship she had with her midwife at the clinic took many weeks to establish. She said she is uncomfortable not knowing who will deliver her child now.

Bratton said she was unable to join another class because she was too far along in her pregnancy. She is now in a labor and delivery class but said “it won’t be the same.” Bratton said she chose MNHC for convenience and the personalized care.

“Maybe a lot of people didn’t know it was there,” Bratton said, referring the clinic’s location on 7th Street. “Maybe if they had promoted it a little more … I guarantee most of the women that live in that area would have been going there.”

Staff members initially went door to door with fliers, attending community meetings and hosting events, according to Saucedo. She said they also walked through the ZIP codes in Milwaukee with the highest infant mortality rates to hang posters in local businesses. However, they struggled to both reach out to people and treat patients at the same time.

‘It’s been really hard’

Nurses who run other clinics in Milwaukee understand the difficulty of sustaining a health center where patients do not have private insurance.

Christine Shaw, a Marquette College of Nursing faculty member and co-founder of the Marquette Clinic for Women and Children, has been maintaining the nurse-run clinic for 18 years. The free clinic, which provides primary care, is open one day a week for six hours. It shares space with the Bread of Healing clinic, located in the basement of Cross Lutheran Church, at 1821 N. 16th St. Only the receptionist is paid – the rest of the staff members are volunteers.

“That is the most difficult part: having a practice that is so heavily (funded by Medicaid),” Shaw said of MNHC. “If you think about the number of patients you would have to see in a day in order to break even, it would be huge.”

MNHC and other nurse-run clinics take the time to educate patients and encourage lifestyle changes that can reduce healthcare costs in the future, according to Zabler. However, it can be difficult for the clinics to quantify something they stopped from happening.

Staff and patients at the Marquette Neighborhood Health Center said the relationships built over the years created a community that they will miss.

“It’s just detrimental to the community we serve,” Saucedo said. “We’ve been serving these patients for a really long time and it’s been really hard these last couple weeks telling them (the clinic is closing). A lot of them have broken down crying. … So it’s just hard.”

This story was originally published by Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service, where you can find other stories reporting on fifteen city neighborhoods in Milwaukee.