Five Neighborhoods With Foreclosure Problems

First in a series on five city neighborhoods that still have many foreclosed and abandoned homes.

The financial crisis that encircled the globe in 2008 brought devastating levels of home foreclosures to Milwaukee’s central city neighborhoods. The effects are continuing to be felt today as the city and many residents struggle to recover.

This special report delves into five Milwaukee neighborhoods: Clarke Square and Layton Boulevard West on the South Side and Harambee, Lindsay Heights and Washington Park on the North Side, focusing on the human impact of foreclosed and vacant housing and the difference committed neighbors can make.

The housing crisis began in 2006 with the subprime mortgage crisis and destabilized neighborhoods as it gathered momentum. While foreclosures were driving down property values, vacant homes were becoming havens for crime. Neighborhood residents, community organizations and elected officials responded, focusing their respective resources and talents on resolving, or at least lessening, the worst effects of the crisis.

Before the housing bubble burst the city typically owned fewer than 100 foreclosed residential properties at any given time. Today, the city owns 1,100 foreclosed homes, according to Aaron Szopinski, Milwaukee housing policy director. He estimates that banks own an additional 1,500 foreclosed properties. And there are approximately 2,800 vacant homes throughout the city, many of which could be foreclosed soon if the owners don’t pay their mortgage or taxes.

Each of these estimated 5,400 foreclosed or abandoned properties had once been home to a family. Boarded up and in disrepair, today they consume police and other city services to provide minimal upkeep such as mowing the grass and shoveling the snow. Most are red ink in the city budget since they are no longer on the tax rolls.

Foreclosed homes tear at the fabric of neighborhoods by increasing drug trafficking, prostitution and other crimes, often committed by gangs. To neighbors living around them, foreclosed homes are a safety threat, a nuisance and an eyesore.

Once a home has been demolished, local residents or the city sometimes plant a garden or build a playground. “It’s a great-sounding situation, but how many gardens can you build in the city? And what happens to the people who lost those houses?” asked Rev. Willie Brisco, president of Milwaukee Inner-city Congregations Allied for Hope.

In late 2007 and into 2008 the deepening economic downturn was fueling unemployment throughout the city and foreclosures were increasing. “We needed to get people moving back into those homes as quickly as possible,” Szopinski said.

Community organizations such as ACTS Housing began working on programs within the city’s Strong Neighborhoods Plan to provide home-buying services to support low-income buyers. “We often work with people who may have never thought homeownership would be for them,” said Michael Gosman, assistant director of ACTS.

The city’s response emphasizes homeownership over demolitions. “Our objective is responsible homeownership,” said Sam Leichtling, program director of the city’s Neighborhood Improvement Development Corp. Nevertheless, neighborhood residents and community activists point to the approximate 400 home demolitions in 2014, a record for the city. The city has sold approximately 1,300 foreclosed homes to new owners during the last five years, increasing the taxable value of homes and saving money in maintenance and management costs, Szopinski said.

In 2015, the city will spend $10.3 million on home loan programs, code compliance loans and other programs. Some city programs allow qualified buyers to take the keys of a rehabilitated, previously foreclosed home for $1. Others provide forgivable loans, or lease-to-own plans that help renters become homeowners.

“Every day we see families who put in incredible amounts of work to make these very challenging properties a home,” Gosman said.

From falling property values in Clarke Square to the Turnkey Renovation Program in Layton Boulevard West; from Habitat for Humanity’s initiative in Washington Park to a Lindsay Heights’ couple’s inspirational commitment to reinvigorate their neighborhood; from flames to frustration in Harambee, foreclosure in Milwaukee is a citywide story, but also a personal one.

Clarke Square

By Ben Greene, Courtney Perry and Patrick Leary

Bernardo Gonzalez has lived at 1127A W. Mineral St. in the Clarke Square neighborhood for seven years. For his first six years on the block, there was a large home located between his property and the street. That changed about a year ago, when the owner deserted the property and the city demolished the home, Gonzalez said.

“It was a nice house, but the owner didn’t want it anymore,” he said.

The city foreclosed on the property due to back taxes, taking ownership of the vacant lot in September.

On the 1100 block of West Mineral Street, there are 14 properties, including the vacant lot in front of Gonzalez’s home and a vacant lot just four doors down. The house on that lot was demolished in November 2012. The block also has one foreclosed house and another home that is heading in that direction.

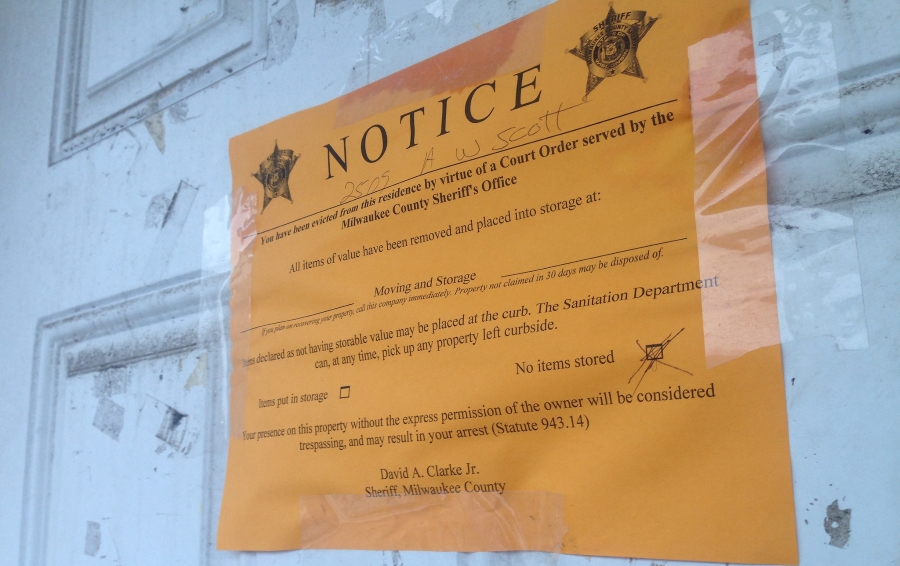

The sign on the lawn of 1119 W. Mineral St. makes it clear the city has demolished this property and wants the public to steer clear.

All four of the struggling properties are located on the south side of the street, while the north side has been relatively unaffected. The average assessed value of the property on the south side of the street is nearly $40,000 less than on the north side.

The city is forced to demolish vacant foreclosed homes because they quickly become popular spots for squatters once the original owners leave, said District 12 Alderman Jose Perez.

“We get phone calls that someone was in the property that was boarded up,” he said. “Either they broke in to do nuisance behavior, or to steal any scraps to get some money out of it. And that provided an eyesore.”

The problem is manifesting itself for a third time, this time at 1115 W. Mineral St., a house that has been abandoned and boarded up for at least five months, according to Rusthman Martinez, who lives on the block.

Perez said that the owner of that property, Isidro Maldonado, died in 2003 and his family took care of the home until deserting it in 2007.

“It’s not clear from the city records what happened to (the property) after his death,” he said. “It wasn’t a mortgage foreclosure and it wasn’t anything against him or his estate but their heirs, whoever, might have just walked away from the property.”

According to Perez, since the owners abandoned the property, the city began noticing that property taxes were not being paid. Last month the city officially took ownership. Perez said the amount of time that the city waits before taking over a property varies.

“We could do it sooner, but usually when you’re already two years behind and there’s no communication, no interaction about paying your property taxes, then in the third year, they’ll start the process,” he said.

Gonzalez and his neighbors are concerned that more vacant properties on the block will hurt already-declining property values. Since 2008, homes on the block have lost 43 percent of their value. Milwaukee as a whole has lost 26 percent of its housing value in that time span, according to Milwaukee Housing Director Aaron Szopinski.

Gonzalez, who has construction skills, said he would like to purchase the property at 1115 W. Mineral St. and fix it up himself. One way the city has been able to turn foreclosed homes over to new owners is through a weekly auction, according to Szopinski.

Gonzalez seems like a good candidate for ownership. He recently had to replace the siding on his own home, but did not want to pay a contractor $5,000 to do the job. Instead, he spent $2,000 on the materials and did it himself. Gonzalez said if he could get a good deal on the house at 1115 W. Mineral, he would be willing to invest his own time and money to repair the roof and windows and flip the home for a profit.

“It wouldn’t take long to fix that up,” he said. “I bet I can fix it in six months.”

Unfortunately, this is often easier said than done, as much of the damage to a vacant home can not be seen from the outside. When homes sit vacant for months or, in some cases, years, they attract some people who are looking for more than just a roof to sleep under. Common Council President Michael Murphy said homes could be stripped of their copper wiring, leaded glass or other valuable architectural items within weeks of being deserted.

When this happens, Murphy said it’s often not worth rehabbing the home, since the amount of money required to fix it up is actually more than the value of the home.

Sometimes demolition is just an unfortunate inevitability, Szopinski said.

“When you have people walking away in big numbers and in big ways, it has a real cost and people don’t see it directly but they see it indirectly,” he said. “They see vacancy and abandonment on the block. They see increased crime. They feel unsafe, even if the crime doesn’t go up because that house is sitting there boarded. Who knows what’s going to happen? It’s very uncertain. Demolition is one thing that we do, and we all hate to do it.”

Article Continues - Pages: 1 2

Political Contributions Tracker

Displaying political contributions between people mentioned in this story. Learn more.

- March 28, 2016 - Michael Murphy received $25 from Aaron Szopinski

Foreclosures Block By Block

-

Clarke Square

Jan 9th, 2015 by Ben Greene, Courtney Perry and Patrick Leary

Jan 9th, 2015 by Ben Greene, Courtney Perry and Patrick Leary

-

Layton Boulevard West

Jan 8th, 2015 by Matt Barbato and Aaron Maybin

Jan 8th, 2015 by Matt Barbato and Aaron Maybin

Clarke Square is west of Cesar E Chavez Drive. 1127 W Mineral is in Walker’s Square.

Foreclosure and abandonment is another symptom of the area’s economic decline and loss of decent quality paying jobs in the region. Wisconsin has lost thousands of middle class production jobs since the 1980s where from the 40s to 70s, a high school graduate could jump right into a decent paying job. A college education is no longer a barometer for economic success. The USA has lost millions of these jobs as well. Walmart jobs are not an equivalent replacement that supports a family.

Detroit lost over 300,000 high paying manufacturing jobs since the 80s and we have seen the negative results of this drastic upheaval. Current government policies nationwide and in Wisconsin do not bode well for the future economic well being of our younger citizens as well as the rest of us that face a continuing downward spiral.

Few politicians have answers as they spin nonsense. Wisconsin has some of the least educated legislators and governor in modern history that are bankrupt on innovation and use ALEC as their fall back for new laws written by corporations to continue fleecing the working citizens and poor.

last 10 years has been disaster for the middle and working classes. What do we need. First we must fix crime and he schools. As for abandoned houses?? what do these aldermen do. Every alderman should know every house that is problem in his district and be working to get people in there to work on them, buy them cheap. Many of these house are very solid, they just need work. i built houses and apts for years. Problem is that govt and these people in govt just cannot handle anything like that. They want tog et money to hire contractors and end up spending over hundred thousand dollars on property worth 50. The whole base of your city is neighborhoods not down town. If neighborhoods are strong so will downtowns. What are we doing?? Arena? Street cars. Both worthless to fix city.

Crime is a vital issue no doubt, but economic development and transportation projects are not exactly worthless to improve the city. Helping the working and middle classes involves more than just fighting crime.

i understand the the Left believes that there is not such a thing as a thug. Of what value is a street car or arena to kids that cannot read and are scared to leave the house cause of drug gangs encouraged by the Left?

The only think worse than an idiot is an idiot who thinks that he’s smart.