The Man Behind Wisconsin’s Iron Mine

Billionaire Chris Cline promises his mine won’t pollute Wisconsin. But his company’s track record mining coal raises doubts.

Unexpected Opposition

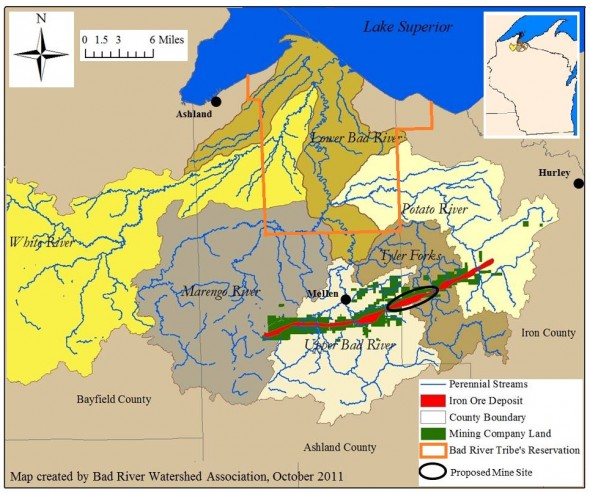

The water-rich Penokee Hills of northern Wisconsin are two parallel ridges that rise 1,200 feet above nearby Lake Superior in a stunningly scenic region. Over 200 inches of snow falls on the Penokees each year, providing plentiful clean water for the Penokee aquifer, the waterfalls in Copper Falls State Park and Lake Superior. The surface and groundwater that flows off the Penokee Hills feeds several major rivers (the Bad, Marengo, Montreal, and Brunsweiler) and provides drinking water for the city of Ashland and nearby towns. The water also feeds the Kakagon/ Bad River Sloughs where the Bad River Ojibwe Tribe maintains the largest natural wild rice bed in the Great Lakes basin. Forty percent of all the wetlands on the Great Lakes are on the Bad River Reservation. This wetland complex has been called “Wisconsin’s Everglades.”

Now imagine a mountaintop removal operation, which blasts the top off the Penokee Hills to extract a low-grade iron ore deposit hundreds of feet below. This would create the largest open pit iron mine in the world, some 4 miles long by 1.5 miles wide and 1,000 feet deep. Over a billion tons of waste rock and tailings created during the projected 35-year life of the mine would be dumped at the headwaters of the Bad River watershed where it could leach toxic metals into the largest undeveloped wetland complex in the upper Great Lakes. Seventy-one miles of rivers and intermittent streams flow through the proposed mining area, emptying into the Bad River and then into Lake Superior.

For the Bad River Ojibwe Tribe, the proposed mine is a literally a life or death issue that could have a disastrous impact on their way of life. When tribal leaders met with Governor Walker in September 2011, they asked that any new mine legislation be based on sound scientific principles. None of the tribe’s 10 principles were considered in drafting the iron mining bill.

The Ojibwe are leading the opposition to the mine, following in the footsteps of other tribes who have opposed mining in Wisconsin. In 1990 the Lac du Flambeau Chippewa tribe joined with environmental and sport fishing groups to oppose Noranda Minerals’ plan to open the Lynne mine in Oneida County, 30 miles south of the Lac du Flambeau reservation. At stake was the contamination of the rich fishing and hunting grounds around the Willow Flowage. The unexpectedly strong opposition, combined with questions about the mine’s potential damage to wetlands, convinced Noranda to withdraw in 1993.

In 1995 the Mole Lake Sokaogon Chippewa became the first Wisconsin tribe granted independent authority by the EPA to regulate water quality on their reservation. The tribe was ready to exercise this authority to protect their wild rice beds from the proposed Crandon mine when the mine owners (BHP Billiton) withdrew from the project and sold the land and mineral rights to the Mole Lake Chippewa and Forest County Potawatomi tribes in 2003. The opposition the company encountered was likely a key reason for the withdrawal.

After spending millions to secure legislation it largely wrote to speed up the permit review process, Cline and his company are no closer to a mine permit let alone any kind of social license to operate, which is now seen as essential for any large scale project by mining investors. But Cline has a history of finding ways to get around mining regulations and there is no sign that Walker or the legislature are backing off on the mine. The battle, in short, is far from over.

Al Gedicks is emeritus professor of sociology at UW-La Crosse and the author of Resource Rebels: Native Challenges to Mining and Oil Corporations (South End Press, 2001). His earlier story for us, “The Fight Against Wisconsin’s Iron Mine,” can be found here.

While I share completely your sentiments, I have to state that not one ounce of iron ore is going to be commercially mined; but not because of environmental reasons, not because of local quality of life concerns, not because of issues with the native americans, and not because of progressive political pressure–no, the mine will never open because it is impossible to make money mining from this deposit. That said, conservatives are sure to place the blame for the eventual re-abandonment of the mine (it was shuttered in 1966 because of cost pressures at the height of the Vietnam War, that should tell you something) with progressives, democrats, native americans and environmentalists.

When Cline Coal was hot to mine this near-vertical deposit of ore the price of iron ore was $180.00 a ton and was thought to be heading towards $200.00 a ton. Just last week the price in Australia (far closer to the China market) was under $80.00(U.S.)/ton, with a major portion of that decline coming in the last 9 months. You cannot, absolutely, mine that deposit of iron ore, and make money at $80.00/ton. Industry observers think the price could reach $60.00 a ton. Mines are closing not only here in the U.S., but in China. Only the very biggest, easiest to mine, with the cheapest labor will be open in six months.

But brace yourself to hear how the environmentalists cost Wisconsin thousands of jobs, how the native americans prevented a major new employer from coming to the North Woods; how the democrats scared off Cline with “uncertainty”.

It is a travesty that the mining jobs touted by the mine’s backers are in the 600 to 700 range (depending on how long the mine would be operated) yet roadblocks are continually put in the way of developing many thousands of renewable energy jobs. Same goes nationwide when you compare the (paltry) number of jobs the XL pipeline might generate compared with the nation renewable potential. Why can’t the dirty power companies simply get on board with making power (and money) in a different way rather than just buying power (the political kind).

Oh yeah….. that would be difficult.

The Upper Big Branch mine disaster was caused by high levels of methane gase. Not coal dust. Is the rest of this story as well-researched?