The Mystery of the Germania Statue

It’s the city’s greatest art heist. How did a monumental, three-ton bronze statue disappear?

In response to the city’s protest against all things German, William Brumder also changed the Germania Building’s nameplate to “Brumder”. The family’s popular almanac “Germania Kalendar” was rebranded as “America Calendar” with the cover of Germania switched out for its French-created competitor, the Statue of Liberty. Most importantly, as the bank president of “Germania National Bank,” Col. William C. Brumder, who was entrusted with printing millions in national currency notes, filed with Congress for a name change to the plain “National Bank of Commerce.”

The Ornamental Iron Shop in its glory days. Courtesy: Villa Terrace Decorative Arts Museum digital collection.

As for the statue, Brumder couldn’t bring himself to have it destroyed and instead called on Colnik and his associates to pull-off their midnight theft. The Milwaukee bronze giantess was skillfully heisted in the night and given shelter by Colnik in his iconic Ornamental Iron Shop several blocks away at 831 N. 8th and Cedar Street (later named Kilbourn Avenue).

Still, that wasn’t enough for Lt. Crozier, who warned the newspapers that “we’re going to clean up the whole edifice,” referring to what was now the Brumder Building. “Look at those Dutch helmets poised on every peak. It’s awful, awful awful…it might not be a bad plan to give a little thought to [Germania-Herold]. I don’t like that name for an American paper.”

But the war soon ended and such feelings began to ebb. By the late 1920s, William C. passed away and the Brumder family began to divest their business interests, including the newspaper by 1927 and finally by selling the building carrying the family name in 1946. Many Brumders left Milwaukee for Oconomowoc, where on Pine Lake they owned 100-acres of waterfront and deep woods, and were often pictured in the newspaper’s society pages offering lunch tours and posting schooner race scores.

E.J. Brumder, the unofficial family historian, recently turned 80 in style but took time out over the phone to relate an interesting story. He once asked his grandfather about the photo of a Germania statue visible in the Pine Lake garden. As the story goes, a scale plaster version of the statue was made at some point but passing hunters kept taking potshots at it until it was ruined. There wasn’t much incentive, it seems, for preserving the family’s old German history.

As for the original statue, it more or less became the property of Colnik after the death of William C. Brumder. It stood in the corner collecting iron forge dust for 18 years while Colnik and his staff worked nearby.

The Austrian-born Colnik first came to America after the German government sent him to work on their display at the famous 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. It was there he became famous and was recruited by Frederick Pabst to move to Milwaukee—the “Deutches Athens” of America—to work for rich, German-American families like Uihlein, A.O. Smith, Brumder and Schlitz. Colnik created masterful ironwork for all the top Milwaukee names and even for awhile owned a historically-forgotten second and larger plant just south of 4th and Burnham (controlling interest was bought out in 1915 by neighboring Bayley & Sons, who were more interested in making lucrative boilers and fire escapes than delicate artwork).

Colnik’s team was as much in demand for fixing pieces of gates and fireplace screens as they were designing whole house pieces. But during the Great Depression, frequent customers like Wisconsin Memorial Park could only pay in trade. Colnik often had to pay his staff with his own money while accepting the payment of such things as burial plot deeds.

In 1936, Milwaukee Journal reporter Edwin Hess was working the boring overnight shift. So he concocted a fantasy where he slipped into Colnik’s workshop late at night and the Germania statue magically came to life for a conversation with the scribe. Hess imagined her as a haughty German society lady interested in gossip and politics and historical events. As dawn approaches, she fades back into being a statue. A sketch of the scene was included by the author in the story—the first time since 1918 that the whereabouts of the Germania statue was revealed to the community.

A few years later, a group of Works Progress Administration writers and photographers toured and researched the state for what became the seminal book “Wisconsin: A Guide to the Badger State” (published in 1941). During their swing through Milwaukee, they snapped the only known photo of the Germania statue in Colnik’s workshop—positioned exactly as depicted in Hess’s story. The photo was never published, but can now be found at the Wisconsin Historical Society’s website in a folder marked “confidential”. A misleading stamp on the photo dates it to Sept. 1942—when the photo was accessed into the museum’s records and not the date the photograph was taken. A handwritten note on it also reports: “formerly on the Germania (now Brumder) Building Milwaukee…at present in the junk heap.”

It’s likely the photo was taken two years earlier than the stated date. For sometime around 1940, Colnik agreed to loan the statue out to a German convention at the very nearby Milwaukee Auditorium (presently the Milwaukee Theatre). Instead of returning it to Colnik’s shop, the 6,000-pound figure was laid down horizontally in a basement corner of the building and forgotten.

Germania’s slumber only lasted until May 1942, when a new world war was raging. Her location was reported to W.E. Simons, the powerful state director of the War Production Board. Simons was becoming famous for getting citizens and businesses to collect record-setting amounts of scrap metal to be salvaged for the war effort. Nothing seemed to escape his grasp, from tin cans to auto yards to whole pedestrian bridges to building ornamentals. That year’s manic quota became known as “All-Out Salvage Drive Unlimited”—seeking 375,000 tons of metal.

Simons sent a wholesale scrap dealer, Clyde Scott, to examine the Germania statue lying in storage. The wholesaler is seen posing next to her in a photograph, estimating her metal worth at $700 (the artistic and collector value was exponentially more, even back then).

Those were sad days for the aging Cyril Colnik. His beloved and spirited wife Marie had just died in 1941 and their daughter Gretchen Colnik moved back from New York to take him in. They moved into a little red-brick house at 531 N. 8th Street where Cyril and Marie once lived upstairs as newlyweds (Marie’s parents lived downstairs).

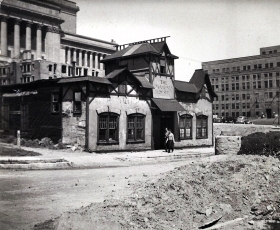

The Ornamental Iron Shop before eminent domain demolished it. Courtesy: Villa Terrace Decorative Arts Museum private collection.

This move to a new home and work location was directly caused by the Milwaukee County government tearing down the neighborhood surrounding The Ornamental Iron Shop for what eventually became the Milwaukee Public Museum and MacArthur Square and thus claiming eminent domain over his studio for demolition.

At his new home, the backyard building became his small workshop while the front parlor displayed his artwork. Colnik was already down from dozens of workers to just a handful and the work was becoming far more specialized. Even if he wanted to take back the Germania statue, Colnik no longer had the space or means to claim her.

In fact, Gretchen and Cyril needed room to buy back some of his own artifacts from houses being torn down or destined for war salvage. Architectural styles were becoming more spartan and efficient. But Colnik could not afford to retire and in any case he was committed to the art of metalsmithing.

In June 1942, a last-second letter came from Washington, DC ordering Simons to think twice before melting down “historical or sentimental items”. By now, Simons had already commanded and scrapped many of the Civil War-era cannons from public parks. Art was secondary to winning the latest war.

Germania’s fate was left back in the hands of Cyril Colnik. He told the newspapers he would be willing to part with it but not at salvage prices being offered. After that, the statue completely disappeared from public record. Cyril Colnik officially retired 13 years later at age 84, and passed away in 1958. Who now was left to champion Germania?

Phenomenal article… nice work guys!

Great right up! More thorough then the old newspaper accounts in the past. Good visuals too.

The best article I’ve read so far from Urban Milwaukee.

Incredible story; very well told. It seems like a long shot, but hopefully one day someone finds this statue.

While I’m sure the history isn’t quite that compelling, anyone have an idea of where the sword shown in this photo from the Aug 7, 1926 (Milwaukee Sentinel) ended up? http://milwaukier-than-thou.tumblr.com/image/57845171826 The base is still in Juneau Park, but it is empty.

Comically enough, Hereiam, on tumblr and flickr I am known as “blurradial”. I knew about this rock for some time and even its origin, but only recently did I begin to wonder what went in the 4-5 inch hole in the top.

After a little searching, I found that photo of the sword in the stone and posted it to M-T-T. It is more likely a vandalism theft, one that no one in Milwaukee remembers or has said anything about even when it happened. So yes, we add the top of an Excalibur sword to a short list of MIA MKE monument and statues. I found most of the others, but not that one.

Sirs/MS: In early 1940’s my Mom worked in Brumder Bldg. downtown. Like many German-speaking central Europeans, the Brumders are, and REMAIN, a cornerstone with their HARD work and genius, inc. positive contributions for what “makes Milwaukee famous!” We can truly be thankful, D. Jaeger PS Thanks for excellent research!

Thanks for the great read, Brian! Discovered this Colnik ad in the City Hall library and thought you might enjoy: http://www.flickr.com/photos/cityofmilwaukee/9516675469/in/set-72157632988298436

Thanks, Tina. I did see that scan in my research–I think it’s from a well-run directory around the turn of the century called “Caspar” (a bookseller in town who published guides, sort of like a Fodor’s meets Yellow Pages). It is important to note the address–Greenbush Street–which led me to Colnik’s unpublished 2nd factory and forge which he was bought out of by 1915.

Gee Whiz B. I just finished page three of your magnificently researched piece. You sure know how to spin a tale. Give us more. Give us more.

Thanks for this great investigative report, even if in the end it remains a mystery (and indeed, a broken-up arm lolling out of a freight cart is so sad). But also thanks for mentioning off hand what happened to all (many?) of the old cannon in city parks and monuments. For a city its size, Milwaukee has virtually no military hardware on display and I could never figure out what had happened to it. Can you tell me if W.E. Simons’ collection reports are available that might have documented what was scrapped?

Great story! Having learned from both Zimmerman and Wilson (author of Colnik book) ; I have heard this story many times over my blacksmith career. Never had I heard some of the follow up. Thanks for keeping Milwaukee history pertinent!