The Mystery of the Germania Statue

It’s the city’s greatest art heist. How did a monumental, three-ton bronze statue disappear?

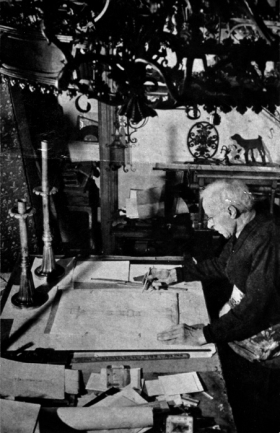

Milwaukee metalsmith Cyril Colnik won world-wide fame for the incredible artistry he brought to railings, gates, candlesticks, chandeliers and more ornamental ironwork—work that can still be seen throughout the city in the Villa Terrace Museum, Pabst Mansion and City Hall. But few know he was a mastermind behind one of the great art heists in the city’s history, snatching and then hiding a three-ton, 10-foot tall bronze statue called “Germania” from the building that shared her name on 2nd and Wells.

This was during World War I when there was civil outcry against such proud displays of German culture, and so the building’s owners asked Colnik to gather a crew of workers and bring down the statue in the dead of the night before it could be vandalized. By the next morning, the statue had disappeared and the building nameplate was chiseled off. Unbeknownst to the general public, Colnik hid the massive bronze lady in the corner of his well-known Ornamental Iron Shop, where it remained for decades.

From there, the story of what happened to the Germania statue becomes something of a riddle—one that is still unsolved. It was apparently loaned out for a convention at the old Milwaukee Auditorium around 1940, later came close to being melted down for scrap, and over the years there were alleged sightings of the statue or perhaps parts of it, and many differing stories were told about it.

It remains one of the great mysteries of the city’s cultural history, one that has endured for nearly a century. Even as a great work of art, Germania is typically not recorded in books or the Smithsonian Institute databases (one theory had her shipped there) whereas other lost Milwaukee public art pieces are fully documented. Why Germania was kept secret reveals much about Milwaukee’s history, its once heavily German culture and a period of revulsion against all things German that altered or destroyed much of that heritage. How she may have met her demise also reveals an unwritten and tragic period in Colnik’s life. It was a monumental piece of Milwaukee history that almost seemed to disappear into thin air.

The story begins after the end of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871, when the Germanic tribes came together as a nation-state to defeat Napoleon III and France. To celebrate Germanic unity, construction was begun on a massive national monument called Niederwalddenkmal, which would overlook the Rhine River. Atop the center pedestal was a 34-foot tall version of the Germania personification. The statue was eagle-armored and robed—proud and majestic with the crown of the Holy Roman Empire in one hand and a Reichsschwert imperial sword in the other. She was flanked by mythical creatures as well as angels representing war and peace.

Meanwhile, the defeated French began work on a solitary figure to honor American independence and their friendship with us that would purposefully dwarf Germania. At 305 feet from ground to torch, Liberty Enlightening the World (the Statue of Liberty’s real name) was dedicated in New York in 1886.

By that time Milwaukee was flooded with immigrants, particularly those of Germanic origin. During the European Revolution of 1848, many German families fled the fighting and arrived in Milwaukee with only the shirt on their back. In not-so-many years, many became captains of industry and brewery masters with millions to their name. George Brumder, who immigrated here from the Alsace-Lorraine region, was among the lucky ones, rising from humble streetcar track layer to bookseller to a publishing and banking magnate by 1896. His flourishing business was due mostly to the prominent Lutheran Wisconsin Synod hymnals and various German-language newspapers and almanacs he published. One of the city’s newspapers, Germania, went from a failing weekly to powerhouse daily under his guidance and melded with the Milwaukee-Herold to become “Germania-Herold” a few years later.

He built an innovative—and until City Hall was built, the tallest—building and printing headquarters at the prime downtown location of Wells, Plankinton and Second Street. He named the five-sided wonder the Germania Building, forgoing the typical family nameplate for the allegorical one instead. The building was topped with giant copper pickelhauben domes with little eagles on the roof and limestone lions beside her. Its centerpiece was a statue commissioned at a cost of $7,500 by Brumder and completed by sculptor Carl Kuehns (famous for works like King Gambrinus and Ringling Brothers wagons) to be an exact one-third scale duplicate of the Germania standing at Niederwalddenkmal in Germany.

For 22 years, she was the pride of the dominant ethnic group in a city where German language newspapers and public school classes were common. During the early days of the first World War, hundreds of thousands crowded the Milwaukee Auditorium for a Charity Bazar “for the Benefit of War Sufferers in Germany, Austria and Hungary” that raised over $160,000 in donations. They felt for the people there and sided with the Kaiser.

Then America entered the war in 1917, fighting on the other side. Suddenly, Milwaukee’s German businesses, food names, cultural events and politics were practically verboten. The Pabst Theater was threatened with a cannon until the stock theater company stopped producing German language plays. The Goethe-Schiller statue in Washington Park was covered up. Street names in German neighborhoods to the west and north were changed to new, Anglicized ones. It was a sorrowful and shameful time for German-Americans in Milwaukee.

Yet there still hadn’t been enough change for a British-Canadian war recruiting officer named Lieutenant A.J. Crozier, who could often be seen scowling in his office space across the street from the Germania building.

This was the kindest thing he said on record. Crozier campaigned hard to have the Germania statue torn down and condoned another reader’s idea of melting her down into bullets “to be launched back at the Huns.”

By then George Brumder had passed away and his son, William C. Brumder was head of the family business. He was very American, a one-time football hero of University of Wisconsin and a rising Republican figure. But William also studied in Strasbourg, Leipzig, and Berlin and understood the importance of German-language publications like “Germania Kalendar.” His brother, George F., serve as publisher of these.

But the well-publicized and continuing wrath of Lt. Crozer was a problem. So William decided to be American and remove the statue.

Phenomenal article… nice work guys!

Great right up! More thorough then the old newspaper accounts in the past. Good visuals too.

The best article I’ve read so far from Urban Milwaukee.

Incredible story; very well told. It seems like a long shot, but hopefully one day someone finds this statue.

While I’m sure the history isn’t quite that compelling, anyone have an idea of where the sword shown in this photo from the Aug 7, 1926 (Milwaukee Sentinel) ended up? http://milwaukier-than-thou.tumblr.com/image/57845171826 The base is still in Juneau Park, but it is empty.

Comically enough, Hereiam, on tumblr and flickr I am known as “blurradial”. I knew about this rock for some time and even its origin, but only recently did I begin to wonder what went in the 4-5 inch hole in the top.

After a little searching, I found that photo of the sword in the stone and posted it to M-T-T. It is more likely a vandalism theft, one that no one in Milwaukee remembers or has said anything about even when it happened. So yes, we add the top of an Excalibur sword to a short list of MIA MKE monument and statues. I found most of the others, but not that one.

Sirs/MS: In early 1940’s my Mom worked in Brumder Bldg. downtown. Like many German-speaking central Europeans, the Brumders are, and REMAIN, a cornerstone with their HARD work and genius, inc. positive contributions for what “makes Milwaukee famous!” We can truly be thankful, D. Jaeger PS Thanks for excellent research!

Thanks for the great read, Brian! Discovered this Colnik ad in the City Hall library and thought you might enjoy: http://www.flickr.com/photos/cityofmilwaukee/9516675469/in/set-72157632988298436

Thanks, Tina. I did see that scan in my research–I think it’s from a well-run directory around the turn of the century called “Caspar” (a bookseller in town who published guides, sort of like a Fodor’s meets Yellow Pages). It is important to note the address–Greenbush Street–which led me to Colnik’s unpublished 2nd factory and forge which he was bought out of by 1915.

Gee Whiz B. I just finished page three of your magnificently researched piece. You sure know how to spin a tale. Give us more. Give us more.

Thanks for this great investigative report, even if in the end it remains a mystery (and indeed, a broken-up arm lolling out of a freight cart is so sad). But also thanks for mentioning off hand what happened to all (many?) of the old cannon in city parks and monuments. For a city its size, Milwaukee has virtually no military hardware on display and I could never figure out what had happened to it. Can you tell me if W.E. Simons’ collection reports are available that might have documented what was scrapped?

Great story! Having learned from both Zimmerman and Wilson (author of Colnik book) ; I have heard this story many times over my blacksmith career. Never had I heard some of the follow up. Thanks for keeping Milwaukee history pertinent!