How Earth Day Turned America Green

Exactly 43 years ago, the first Earth Day, founded by Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson, launched a national movement.

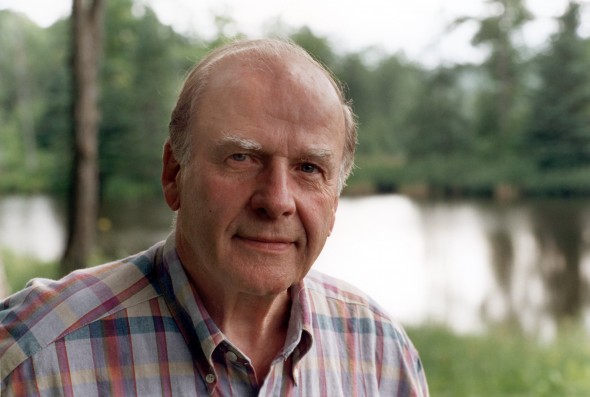

Gaylord Nelson. Photo by Fritz Albert.

On a remarkable spring day, April 22, 1970, environmental activism entered the mainstream of American life and politics.

It was Earth Day, and the American environmental movement was forever changed. Twenty million people – ten per cent of the United States population – mobilized to show their support for a clean environment. They attended marches, rallies, concerts and teach-ins. They planted trees and picked up tons of trash. They confronted polluters and held classes on environmental issues. They signed petitions and wrote letters to politicians. They gathered in parks, on city streets, in campus auditoriums, in small towns and major cities. The weather cooperated; in most of the country, it was a clear and sunny day. The news media also cooperated, and covered the event extensively.

Fifth Avenue in New York City was closed to traffic for two hours, and a photo of tens of thousands of New Yorkers strolling and jamming the temporary pedestrian mall dominated the front page of the next day’s New York Times. An estimated one hundred thousand people took part during the day in activities at Union Square, the center for speeches and teach-ins. Mayor John Lindsay set the tone in a brief speech, saying that environmental issues might sound complicated, but it all boiled down to a simple question: “Do we want to live or die?”

In Chicago, the sun seemed pale and distant on Earth Day, and the city’s monitoring devices showed levels of sulfur dioxide in the atmosphere above the danger point for infants and the elderly. Several thousand persons attended a rally at Civic Center Plaza, where Illinois Attorney General William Scott declared that he would sue the City of Milwaukee for dumping sewage into Lake Michigan. The Chicago Tribune ran front page side-by-side photos taken during and after the rally, showing an amazing sight. When the demonstrators left, “there was no post-rally litter remaining to be cleaned up,” the newspaper reported.

At the Washington Monument, a crowd of ten thousand gathered to hear folk music from Pete Seeger and Phil Ochs and speeches by Senator Edmund Muskie, muckraker I.F. Stone, Chicago Seven defendant Rennie Davis, and others. Earlier, 1,700 people had marched to the Interior Department offices to leave symbolic puddles of oil on the doorstep, and some Connecticut Girl Scouts in canoes had pulled tires and debris from the Potomac River [1]. In Philadelphia, twenty-five thousand people heard Muskie call for “an environmental revolution” and criticize government priorities that spent “twenty times as much on Vietnam as we are to fight water pollution, and twice as much on the supersonic transport as we are to fight air pollution.”

Congress had adjourned so its members could go home and give Earth Day speeches. For many, it was the first time they had given an environmental speech, and they drew heavily on material from the office of Senator Gaylord Nelson, Earth Day’s founder. At least twenty-two U.S. Senators participated, as did governors and local officials across the nation. The governors of New York and New Jersey signed laws creating new state environmental agencies. The Massachusetts legislature passed an environmental bill of rights. President Nixon, through an aide, said he had said enough about his concern about pollution and would be watching, rather than participating in Earth Day, and hoping it would lead to an ongoing anti-pollution campaign. Nixon had, in fact, in his State of the Union speech three months earlier, called for a national fight against air and water pollution.

Automobiles were pounded, demolished, disassembled, and buried. School children and adults alike collected trash and litter from roadsides, parks, streams and lakes. In Ohio, students put “This is a Polluter” stickers on autos, and at Iowa State and Syracuse Universities, students blocked autos from coming onto the campus. In Tacoma, Washington, one hundred students rode down a freeway on horseback to protest auto emissions. In Cleveland, one thousand students filled garbage trucks with trash. In Appalachia, students buried a trash-filled casket. California students cut up their oil company credit cards. In Coral Gables, Florida, a demonstrator paraded with dead fish and a dead octopus in front of a power plant.

But the real focus was the schools. The National Education Association estimated that ten million public school children took part in Earth Day programs. Earth Day organizers said two thousand colleges and ten thousand grade and high schools participated.

In Clear Lake, Wisconsin, Gaylord Nelson’s hometown, junior and senior high school students observed Earth Day at a school assembly with speeches, songs, and skits, then cleaned up more than 250 bags full of litter from the streets and highways in and around the village. A photo of young “demonstrators” with picket signs ran on page one of The Clear Lake Star the next week.

Many businesses put their best faces forward and joined the call for a cleaner earth. In New York, Consolidated Edison supplied the rakes and shovels used by school children cleaning up Union Square, and provided an electrically powered bus to take Mayor Lindsay around the city. Scott Paper, Texas Gulf Sulphur, Sun Oil, Rex Chainbelt and other companies used the occasion to announce projects to clean up or control pollution. Continental Oil introduced four new cleaner gasolines, ALCOA ran newspaper ads touting a new anti-pollution process at its plants, and Republic Steel sent twenty-five company executives to speak at high schools and colleges.

The business participation drew a mixed reaction. Organizers said some companies spent more advertising their support of Earth Day than on Earth Day itself. General Electric stockholders met in Minneapolis, to be greeted outside by a protestor dressed as the Grim Reaper and later were confronted in the meeting by a student leader demanding that the company refuse war contracts and use its influence to channel government expenditures into protecting the environment instead.

Article Continues - Pages: 1 2