Arnoldo Sevilla

A Hispanic activist and part-time historian reflects on how things have changed.

Historian and champion of Mexican-Americans, Arnoldo Sevilla addressed the crowd in a powerful voice on September 16, 2012, at the United Migrant Opportunities Services’ 44th year celebration. Thousands gathered to cheer him during his rendition of “El Grito de Dolores,” (The Cry of Dolores), the famous speech that was the flint that sparked the Mexican War of Independence against the Spanish colonial government in 1810.

“Viva Mexico! Viva la Independencia!” The crowd echoed the words of Sevilla, 72, who is among the 6.1 percent of Wisconsinites who are Hispanics, according to the most recent count by the U.S. Census Bureau. Nationally, Hispanics now comprise the largest ethnic minority, but in Wisconsin they still trail African Americans (6.5 percent of the population). But the Hispanic impact is growing. In Clark County, Wisconsin, for instance, Latino immigrants make up 40% of the dairy farm workers, Wisconsinwatch.org reports. Wisconsin’s dairy industry now depends on Latino labor.

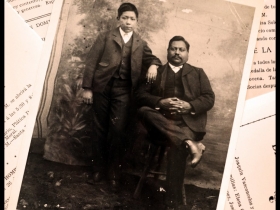

Sevilla mentions “cheap labor, and the strong work ethic of Latinos,” as he lays out dozens of historical documents and photographs, including one of Rafael Baez, the first known Latino in Milwaukee. Sitting at a table at the United Community Center’s Senior Center on the near South Side for an interview with Urban Milwaukee, Sevilla says he doesn’t like talking about himself, but his words tumble forth in eloquent but slightly imperfect English, a language he didn’t learn to speak until he was in his mid-thirties. Yet he would help document the Hispanic history in Milwaukee.

Several decades ago, he culled words from interviews in Spanish and English, that are now part of the Wisconsin Historical Society archives, housed at the UW-Milwaukee Library. In 2006, Sevilla contributed photos for “Latinos in Milwaukee” (Arcadia Publishing). Printed entirely in the U.S.A., and available at Boswell Bookshop, the book has a photo of Arnoldo’s father, Miguel Sevilla Chavez, posing near a fine automobile somewhere in Milwaukee. Miguel had fled from Mexico in 1926, to escape oppression by the Catholic Church. Arnoldo says his grandmother was murdered in 1926, in Mexico, caught in the brutal oppression of the Catholic Church and an armed insurrection by a group allied with the Church known as Los Cristeros.

Back in Milwaukee, it only took four years for Miguel to woo and then wed Ana Wrobel, a Polish girl. Back to Mexico they went, to raise an even-dozen kids in the town of Tuxpan in the state of Michoacan. For Arnoldo, life in Tuxpan was good, as was life in Mexico City where he studied at the National School of Teachers and earned his first degree. He taught in Mexico for a decade before coming to Milwaukee in 1969 — undocumented, but on the track to becoming a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1976. Three of his siblings also settled in Milwaukee.

“Like most immigrants,” he says, “I came in search of a tiny piece of the American Dream, plus, I wanted to meet my mother’s family and learn more about not only my Polish roots, but about my father’s involvement as a “Primero” in Milwaukee’s Latino community. In his short time in Milwaukee, Arnoldo’s father co-founded “a social circle for friends,” and Milwaukee’s first Spanish-language newspapers (Sancho Panza and Boletin Informativa). Arnoldo and his brother, too, would have a major impact on Milwaukee’s Hispanic community.

On election day, Arnoldo will shepherd approximately 50 Latinos to the Frank P. Ziedler Building on Broadway, where he will assist them in registering and casting their votes. (He supports another term for Obama, but doesn’t believe all immigrants should be part of the “Dream Act.”) “Helping each other was part of my early life,” he says, adding that all of his siblings are social activists. One of his brothers, Carlos, arrived here in the 1950s and went on to become a director of El Centro Credit Union, and the first Hispanic Director of the Spanish Center. In a 1971 photo from La Guardia, Carlos is pictured talking with Governor Patrick Lucey about police brutality, the need for education, improved housing, and job opportunities.

Arnoldo’s first job in Milwaukee was as a bookkeeper for UMOS, and he later became state coordinator for the Wisconsin Christian Council for Spanish Speaking Affairs. He went to work as an analyst for the City of Milwaukee Commission on Community Relations, and soon was transferred to the Department of City Development and Neighborhood Relations.

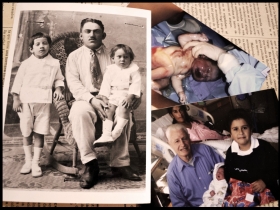

What does he do now, in his retirement years? Well, he’s a volunteer commissioner for the Milwaukee County Department on Aging and a volunteer for UMOS and other community agencies. He’s also a busy family man: in 2004, at the age of 64, he was married for the second time, and in September, a daughter (Julie Ann Sevilla) was welcomed into the Arnoldo Sevilla family, joining her brother. The family of four lives on N. 69th St.

And what does he most want for his family? “I yearn for my children to become better than me,” he says, as he studies a color photograph of the exact moment of the birth of his new daughter.

“Latinos in Milwaukee” notes that Milwaukee police were wary of Latino immigrants; In the 1960s, police harassment was mentioned in nearly every issue of the community newspaper “La Guardia. Arnoldo was active in many causes, including the sit-ins in Madison. But he avoided being in the spotlight because he was waiting for naturalization. Meanwhile, times have changed: In 1989, Milwaukee had its first Latino police chief, Philip Arreola, who served until 1996. But the problem of discrimination hasn’t disappeared.

“Even today, people display racist behavior,” Arnoldo says, adding that “a recent study states that more than one-third of all Americans believe that every Latino residing in this country is here illegally: Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, Central and South Americans, you name it. We all seem to be a bunch of illegal immigrants. As for changes, we see many Latinos achieving higher education, and becoming leaders in the overall community.”

The American Dream. The Dream Act. And Arnoldo’s dream? A little more local. “I’d like to write,” he says, “an extensive history of the early days of the Latino Community in Milwaukee.”

City People

-

New Public Allies Leader Comes Full Circle

Nov 2nd, 2021 by Sam Woods

Nov 2nd, 2021 by Sam Woods

-

Dr. Lester Carter, a Community Anchor for 47 Years

Jul 2nd, 2021 by Damia S. Causey

Jul 2nd, 2021 by Damia S. Causey

-

Reuben Harpole Found His Purpose

May 13th, 2021 by PrincessSafiya Byers

May 13th, 2021 by PrincessSafiya Byers

During this past Open Doors Milwaukee, Mr Sevilla led a tour of the near south side of Milwaukee where the first Spanish speaking immigrants settled in Milwaukee. He is a friendly, outgoing man with a big heart. In the Acknowledgements section of the book, Latinos In Milwaukee, it says this: “When Miguel Sevilla Chávez, among Milwaukee’s early Latino immigrants, returned to Mexico during the Great Depression, he never dreamed that one of his future children would return to the city and become the Latino community’s unofficial historian. Arnoldo Sevilla’s amazing collection of photographs, passion for local history, and unflagging enthusiasm have been vital to this book. We could not have done it without him.”

I don’t know if UWM has an oral history department, but if they do, they should really try to record a series of interviews with this man.

Arnoldo Sevilla is undoubtedly the Milwaukee area’s expert on the history of Latinos in Milwaukee. I hope that he is able to do a book on the history of Los Primeros in Milwaukee.

hi dad