A trail well-traveled

A Survey: Drawings & Paintings by John Wickenberg

March 19 – May 18

Charles Allis Art Museum

1801 N. Prospect Avenue

John Wickenberg studied under the guidance of another John (Wisconsin’s own John Wilde); the ghost of his late teacher, who died in 2006, lingers in A Survey: Drawings & Paintings by John Wickenberg (now – May 18 at the Charles Allis Art Museum). Laurel Turner, the curator of exhibitions and collections at both the Charles Allis and Villa Terrace, surely had her hands full dealing with the proliferation of various art mediums in the show: watercolor/gouache, watercolor/pencil, silverpoint/acrylic, silverpoint/oil. In preparing for this review, I visited the Print, Drawing, and Photography Study Center at the Milwaukee Art Museum, and was told by a helpful staffer that the Center had none of Wisconsin-based Wickenberg’s works. For his part, John Wilde has been variously defined as a magic realist, a surrealistic and a fantasy painter, but Wickenberg doesn’t exactly fit into these niches. It’s doubtful that he’d appreciate being pigeon-holed. “The basis of my technique is a strong commitment to the craft of drawing,” he says. Period.

Wickenberg (who earned his Bachelor’s and Master of Fine Arts degree from UW-Madison, and later taught at UW-Whitewater) depicts everyday objects, so I was pleased to locate a mixed-media Joseph Cornell box (“Celestial Navigations by Birds, 1958”) in MAM’s Gallery 18, and upstairs, Georgia O’Keeffe’s 1936 “Mule Skull with Turkey Feather.” Her pretty paintings bore me in the way that Milton Avery’s work bores me, but at least her skull and feather painting is a still-life statement about life and death, and it thrust me forward to further explore. In the Education Gallery on the main level, I paused to see what they had to offer, and it turned out to be what I was seeking: a nice selection of graphite drawings with watercolor by Wisconsin-based artist Joanna Poehlmann. Her beautifully drawn “Nest Egg VI” (2006) echoes both Wickenberg and Wilde, who accomplish the extraordinary via the ordinary.

To clear my head, I had to remind myself that all art starts with a blank and goes (successfully or unsuccessfully) from there. Prior “understanding” of particular works tends to muddy the field, which ideally should be level and clear of pre-conceived notions, so I leave it to art historians to trace the art of the still-life back to the efforts of Renaissance masters.

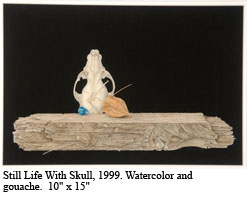

“All art,” John Wilde wrote, “comes from sex and the awareness of death.” On floor two of the Allis, in the main gallery space, are seven watercolor and gouache paintings depicting nests: empty nests, nests with feathers, nests with eggs (albeit “abandoned”). Despite the richness of detail, and because of the barely-there use of color, they float pristine on backgrounds as black as night. Never has still-life seemed so still.

A tiny adjacent room outside of the main gallery on floor two holds further examples of his dedication: an oddly wonderful “Julian Schnabel (study for the Great Living Painter Series, 1987)” and an assortment of watercolor and pencil drawings addressing issues of a consumer society slowly drowning in what it’s gobbled, burped and exploded across the land.

A tiny adjacent room outside of the main gallery on floor two holds further examples of his dedication: an oddly wonderful “Julian Schnabel (study for the Great Living Painter Series, 1987)” and an assortment of watercolor and pencil drawings addressing issues of a consumer society slowly drowning in what it’s gobbled, burped and exploded across the land.

Wickenberg lives near Dousman, not far from the South Kettle Moraine unit where I’ve often hiked along the Scuppernong trail when spring trumpets the arrival of marsh marigolds and skunk cabbage. He’s captured seasonal changes in the brushy growth in a series of small, tightly focused, horizontal works and it’s easy to image him trekking the trail, pausing to pick up invasive trash left behind by those who aren’t committed to anything but consumerism.

A modest selection of the artist’s work is also installed on the west wall of the rather problematical Great Hall on floor one, a space where the glare of light from the east facing windows bounces off any work framed under glass. Nothing is ever perfect, but curator Turner, youthful and energetic, has served this artist well. Artists who gripe that they’re being “pushed aside” by blockbuster shows and hi-tech methods of art-making will perhaps take pause at the Allis and consider what real commitment entails.

Should you wish to expand your education in the arts, visit Anne Miotke’s selection of still-life watercolors at Tory Folliard Gallery in the Third Ward. The most successful are her simple studies of everyday objects. Folliard also handles the work of the late great John Wilde. VS