State’s Drinking Water Has Lead Dangers

Percent of lead-poisoned children in Wisconsin nearly as high as in Flint.

Thousands of children affected in Wisconsin

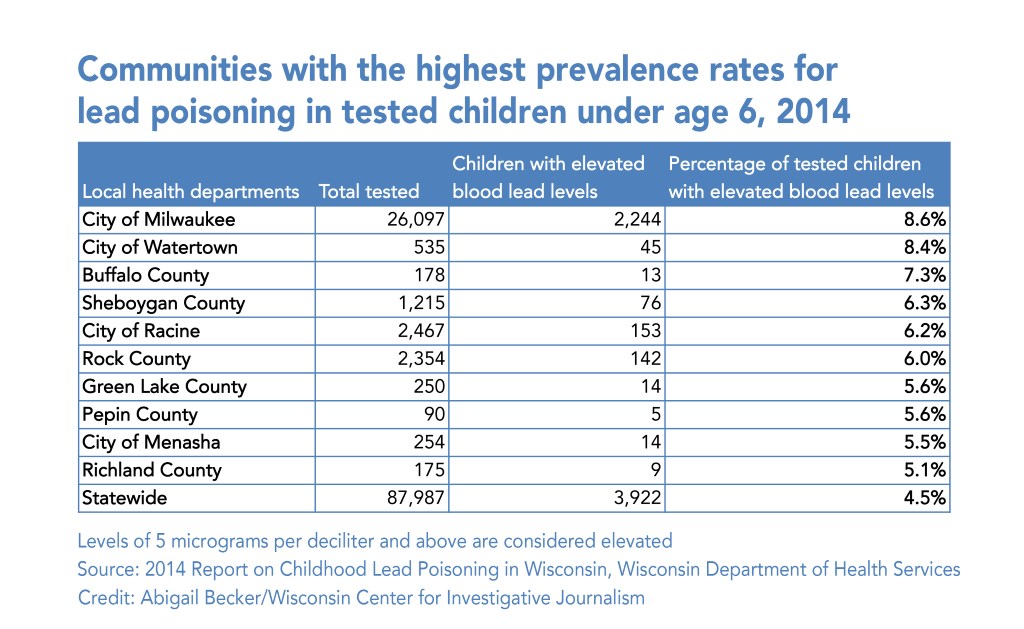

In 2014, 3,922 Wisconsin children under age 6 had blood lead levels of 5 micrograms per deciliter or higher. About 20 percent of Wisconsin children are tested in a typical year.

Communities with the highest prevalence rates for lead poisoning in tested children under age 6, 2014.

The Wisconsin Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program provides technical assistance, funding and consulting to health providers to prevent, detect and treat childhood lead poisoning. It projects lead-poisoned children “will likely cost Wisconsin billions of dollars in reduced intelligence quotient (IQ), lifetime earning losses and the associated societal costs for health care, education and correctional services.”

Almost 60 percent, or 2,244, of the state’s lead-poisoned children in 2014 were from the city of Milwaukee.

Ramona Jensen, lead liaison for Milwaukee’s Social Development Commission, wonders when officials will finally begin investigating tap water as a potential contributor to lead poisoning in Wisconsin’s children.

Jensen’s organization, which plans, coordinates and provides human service programs to the poor in Milwaukee County, is wrapping up work on a multi-year, $3 million U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development-funded project to identify and remove lead hazards from 231 low-income housing units. Yet drinking water is not part of the program, she said.

“We just quite honestly don’t consider the water,” she said. “We were just painting and replacing siding and things like that — everything except the water, frankly. If you’re not testing the water when you’re doing a (lead) investigation, how do we know if it is or is not an exposure route?”

Lead in drinking water “doesn’t get the attention and it doesn’t get the media (coverage) it should,” Jensen added. “I know some of the experts … actually feel like we’re ignoring the water problem completely, and to some extent, I think that’s true.”

Blood lead level lowered, water standard same

In recognition of lead’s high toxicity, in 2012 the CDC cut in half the amount at which a child’s blood lead level requires reporting and possible intervention from 10 micrograms per deciliter to 5.

But the nation’s standard for lead in public drinking water has not been updated since 1991 when the EPA’s Lead and Copper Rule took effect. The federal law aims to keep lead levels in water below 15 ppb, while standards for lead in Canada and the European Union match the World Health Organization’s guideline of 10 ppb.

Recommended changes to the 25-year-old Lead and Copper Rule, a federal law designed to eliminate lead from drinking water, include requiring water utilities to replace all lead pipes in their systems. Photo courtesy of the Madison Water Utility.

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources has oversight over public water utilities, which must provide drinking water that meets state and federal health standards.

But public water utilities are required to take remedial action under the Lead and Copper Rule only if more than 10 percent of household tap water samples exceed 15 ppb. No remediation is required for even exceedingly high readings if the 10 percent threshold is not met.

In Wisconsin, 725 tap water samples, or 3.5 percent of almost 21,000 household samples tested between January 2010 and April 2015, exceeded 15 ppb, according to a DNR database analyzed by the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

Applying the 3.5 percent estimate to the 176,000 known lead service lines in the state suggests that some 6,200 Wisconsin households may drink public water that exceeds the federal standard. That does not account for the unknown number of homes with lead fixtures.

In 2013, the Department of Health Services analyzed almost 4,000 private well samples and found that 1.8 percent of them exceeded 15 ppb of lead. Applying this estimate to all homes on private wells adds nearly 17,000 households to the at-risk total.

When public and private well calculations are combined, they suggest that residents in roughly 23,000 homes in Wisconsin may be consuming unsafe levels of lead in their water.

The percentage of public water samples that tested above 15 ppb was much higher than 3.5 percent in some Wisconsin communities, such as Lake Mills (20 percent), Columbus (18 percent) and Mount Horeb (16 percent).

Milwaukee, which treats its Lake Michigan-sourced water with chemical corrosion control to reduce lead leaching, had just two results above 15 ppb since 2010. However, only a small fraction of its 70,000 buildings on lead service lines have to be tested regularly to remain compliant with the Lead and Copper Rule.

Of the state’s nearly 21,000 recent test results, 202 exceeded 50 ppb, more than three times the federal standard. The state’s highest value was recorded in 2012 in Mount Horeb: 9,370 ppb.

Lead in water, blood linked

Some of the strongest evidence linking lead-contaminated water with children’s blood lead levels has come from studies directed by Edwards in two cities: Washington, D.C., in the early 2000s, and Flint, Michigan, beginning last summer.

Edwards and colleagues demonstrated in 2004 that lead increases in the water of thousands of D.C. households were triggered by a change in the water utility’s disinfectant protocol. In a 2009 study, he then showed the change caused a more than four-fold increase in the number of children under 16 months with blood lead levels exceeding 10 micrograms per deciliter.

Edwards and many other scientists have continued to evaluate, and confirm, a strong relationship between lead in water and blood since then.

A 2012 federally funded study by Edwards found that while lead poisoning among children had decreased thanks to reduced lead exposure from gasoline, paint and other sources, the relative importance of water had increased. A 2014 Canadian government-funded study that examined paint, dust and tap water as exposure sources concluded that drinking water was “a persistent significant contributor to children’s blood lead levels.”

Another Canadian study from 2015 estimated that an increase of 1 ppb of lead in water “would result in an increase of 35 percent of blood lead (in young children) after 150 days of exposure,” and concluded that “water lead concentrations well under the current drinking water guidelines in Canada (10 ppb) and the United States (15 ppb) could have an impact on blood lead levels of young children after long-term exposure.”

Source investigations ignore water

In July 2013, Crystal Wozniak of Green Bay learned that her 9-month-old baby Casheous had 18 micrograms per deciliter of lead in his blood — more than three times the federal threshold. The finger prick test that Casheous received is mandatory for children, generally beginning at age 1, who are covered under BadgerCare, Wisconsin’s health care program for low-income families.

“When (the nurse) broke the news to me,” Wozniak said, “I was devastated. My heart broke, I cried. I was very worried for him and had no knowledge of what to do next.”

Since then, Wozniak has been consumed with eliminating lead from her son’s environment.

“It’s just everywhere, it gets really tedious. It sort of takes over your life,” she said.

Wozniak thinks her son may have chewed on her bedroom windowsill when he woke up before she did about two weeks before the test.

In an investigation following Casheous’ diagnosis of lead poisoning, the Brown County Health Department identified multiple sources of deteriorating lead-based paint in Wozniak’s home, built in 1900. Eventually, the house was gutted, and Wozniak moved elsewhere.

But she wondered why nobody talked about lead pipes or urged her to get her tap water tested.

A source investigation triggered in Wisconsin by a case of childhood lead poisoning does not require testing the tap water in the child’s home or daycare, despite the documented link between water lead and blood lead levels. The CDC guidelines also do not specifically recommend examining drinking water.

Later testing of Wozniak’s tap water found no lead, but even EPA officials acknowledge that “the existing regulatory sampling protocol … systematically misses high lead levels and potential human exposure.” The city of Green Bay, where Wozniak lived, had a maximum lead level of 490 ppb in one of its tested households in 2012.

Lambrinidou, the Virginia Tech scientist, said regulatory agencies fail to examine lead in water or alert homeowners of ways to protect themselves, including installing filters costing as little as $40.

“Lead in drinking water has been pushed under the rug by almost every single agency,” she said. “Lead particles (in water) can contain far more lead than lead paint chips and can spike a child’s blood lead level literally overnight, and cause irreversible brain damage from one glass of water or one bowl of pasta.

“The outrage,” Lambrinidou added, “is that for many households, the prevention of miscarriages and of irreversible brain damage is $40 away.”

Casheous, now 3 years old, has had a steady decrease in his blood lead levels since his original test. Wozniak’s experience with a lead-poisoned child has prompted her to reach out to other families whose homes could be lead-contaminated. In collaboration with the Lead Safe America Foundation, she has distributed free testing kits for lead paint at Green Bay events.

For her part, Jensen, of Milwaukee’s Social Development Commission, gives regular public presentations about the dangers of lead and trains landlords on how to reduce lead exposure. She says there is a “knowledge gap” when it comes to lead in water, as many people do not know if they have lead plumbing or solder and remain unaware of the danger they pose.

“You never see (public service announcements) about lead,” Jensen said. “That should be a constant, in my mind. It’s very frustrating. You feel like the voice in the wilderness.”

This January 2015 protest in Flint, Michigan, highlighted the dangerous levels of lead that appeared in the city’s water after it switched to a less expensive water source that also was more corrosive, scouring lead from old water pipes. Lead is a powerful toxin that can cause permanent brain damage and behavior problems in children. Photo by Steve Carmody of Michigan Radio.

In Michigan, Gov. Rick Snyder apologized for the Flint lead crisis during his State of the State address Jan. 19 and asked the Legislature for $28 million to replace faucets and fixtures at schools and other public buildings, provide home water filters, conduct additional blood lead testing and continue to have National Guard troops distribute bottled water to Flint residents.

But parents like Wozniak, professionals like Jensen and scientists like Lambrinidou and Edwards want more than apologies. They believe drinking water must be added to the list of exposure sources that public health officials routinely investigate for any lead-poisoned child.

“I don’t understand why they don’t address the water,” Wozniak said. “If the pipes are lead contaminated, they should use the same process as they do for replacing all the trims, windows, doors and kitchen cabinets in your house.”

Added Wozniak, “It’s essential for life to have water. It should fall in the same category and be tested along with everything else.”

The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Article Continues - Pages: 1 2

Tainted Water

-

Fecal Microbes In 60% of Sampled Wells

Jun 12th, 2017 by Coburn Dukehart

Jun 12th, 2017 by Coburn Dukehart

-

State’s Failures On Lead Pipes

Jan 15th, 2017 by Cara Lombardo and Dee J. Hall

Jan 15th, 2017 by Cara Lombardo and Dee J. Hall

-

Lax Rules Expose Kids To Lead-Tainted Water

Dec 19th, 2016 by Cara Lombardo and Dee J. Hall

Dec 19th, 2016 by Cara Lombardo and Dee J. Hall

This article does not address the variable in question, which is lead laterals. For the most part, lead in the drinking water supply is discussed, but that does not include the laterals. From a scientific method perspective, this article does almost nothing to convince me that laterals that are chemically treated have higher lead concentrations than non-lead laterals.

The article does acknowledge this information is not widely available. Is it not then reasonable that the water supply, while a scary scenario, is not really the likely source of lead? Especially in communities that treat their water like we do?

The DC study shows how lead in water IS dangerous. What no available information shows is that lead laterals are the problem. Per the Milwaukee Water Works in their article in the JS, lead levels in lead lateral homes was within acceptable limits within a week or two of disturbing the lateral.

I’m not dismissing this issue, but there is some scaring of the public going on here with lead laterals.

Lead and other heavy metals like tin, mercury, and aluminum have no use in the human body and cause damage in many ways. There are thousands of lead laterals in Milwaukee’s distribution system in older parts of the city. Lake Michigan pH levels are neutral and above and less chemically reactive at leaching lead from the lateral tubing. As a precaution, always run water for a minute or more, until cold, before using for drinking, making coffee. This removes the overnight standing water in the laterals and plumbing and fittings.

Children, babies, and pregnant women, are the most susceptible to lead risks since they have smaller bodies. They are closer to the ground as well. Living in a pre-1978 home with decaying dusty lead paint is the highest risk. Windows, doorways, and porches are the risky areas. Children play around these areas and can pick up the dust on hands, and put hands in their mouths, leading to higher doses. Use of a HEPA vacuum and wet wiping areas lowers the risk in an older home.

The Sistine Chapel is painted with lead coating. No one is calling for removal of this painting.

Nutrition plays a role in lead poisoning. A child that has a good diet with calcium helps prevent higher lead doses. Lead readily substitutes for calcium where it is needed in the body. Adults can be poisoned as well. Always wash hands before handling food and eating.

The natural lead in soil levels is around 50 ppm. The base of older pre-1978 housing and garages can be much higher levels of lead in soil, due to flaking lead paint over the decades. Along road ways and freeways, the levels in soil are likely higher due to the prevalence of lead in gasoline years ago. Children playing in soil can lead to poisoning, and adults growing vegetable gardens in high level lead soils can lead to accumulations in humans.

While concerns over lead poisoning are valid, the author’s alarmist discussion about lead laterals leaves out some important points… Those lead pipes have been in use for many years and are coated with rust and deposits that prevent the water from coming into contact with the lead. What happened in Flint was that the switch to corrosive river water removed these deposits, allowing lead to leach into the water. Unless the laterals have been disturbed, as was happening in Milwaukee with new mains being installed, lead should remain at negligible levels. The article did not mention that the water in a home that has lead laterals is most likely very safe.

30 years ago I noticed the lateral to my first home in Sheboygan was of lead pipe, and had it tested. It was fine, and I was given this explanation. If you have an older home with dark-colored pipe leading to the meter, do the magnet test, and if it’s lead don’t panic, just get it tested.