10 Examples of The Classical Style

Where to find the best examples of classical style in town.

In the western architectural tradition there is arguably no school more important than classical architecture, which is derived from ancient Greek and Roman models. Dozens of individual styles ranging from Second Empire, to Colonial, to Stalinist all draw from the constellation of motifs and logics encompassed by this architectural cannon. At various points it has stood for American republicanism, bourgeois excess, Protestant asceticism, absolute monarchy and fascism. For anti-modernists like architect Leon Krier it is our salvation from the crushing orthodoxy of contemporary architecture, while noted British anarchist and writer Herbert Read offers this complaint: “In the back of every dying civilization sticks a bloody Doric column.”

The classical tradition’s most immediately identifiable characteristic is its columns. Vitruvius identified three orders of Greek columns: Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian, as well as one native Italian variation, Tuscan. A later Roman innovation, the Composite column, which fuses Ionic and Corinthian together, is also a part of the classical canon, however for the sake of brevity we will stick with the original Vitruvian four.

The classical orders are usually presented as a hierarchy arranged from most basic to most elaborate beginning with the Tuscan order, which can be seen locally on the Headquarters Building at the Old Soldiers’ Home Historic District (1896). This restrained cream brick building, which was originally administrative offices, has six white Tuscan columns across its front portico, the covered space between the columns and the entrance.

Headquarters Building

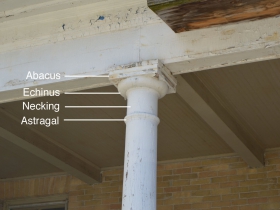

Vitruvius carefully described the proportions of “Tuscanicae” temple columns, however he did not describe any of the details nor provide any examples. It is likely he was attempting to add a native Italian order to what was otherwise a very Grecian architectural tradition, most likely by drawing on some sort of older Etruscan model. The Tuscan order, as we understand it today (a simplified Doric column, the next column in the hierarchy), was invented by architects like Andrea Palladio (1508-1580) after the rediscovery of Vitruvius’ writings in 1414. Because it is the simplest order it is also a good place to begin identifying the different parts of a column. Generally speaking classical columns are broken down into three parts: the base (the portion closest to the ground), the shaft (the vertical, elongated portion in the middle) and most importantly the capital (the top of the column at the end of the shaft). As we move our way up the orders these sections will add more internal components unique to that order.

The distinction between Tuscan and Doric is the hardest to make, but a good general rule of thumb is that the capital of a Tuscan column only has three parts (the abacus, echinus, and astrugal) while the capitals of Doric columns, like those found at the Edward Diederich House (1241 N. Franklin Pl., built 1855), have a number of extra fillets or bands adorning these same parts. Of particular note on this building is the entablature, the ornamented, horizontal band supported by the columns. As with columns the entablature can also be broken down into three basic portions: the architrave (lowest portion), the frieze (the middle section) and the cornice (the protruding top portion). The entablatures for each order of column have distinct elements and unique to Doric entablatures are triglyphs, the three-part vertical elements arranged at regular intervals in the frieze of this house. Triglyphs are thought to be vestigial reminders of beam-ends from older wood and stone post and lintel buildings.

Edward Diederich House

This capital, shaft and base formula is found in all Vitruvian orders, save for one exception that slips its way into the canon and that is the Greek Doric column like those seen on the Mechanics National Bank building (2683-87 S. Kinnickinnic Ave., built 1925). These columns are based on older Greek models like those at the Parthenon, and distinguished by simpler capitals and shafts that go all the way to the ground with no base or, like here, into a simple plinth, an architectural element that is sometimes added between the base of a column and the ground.

Mechanics National Bank

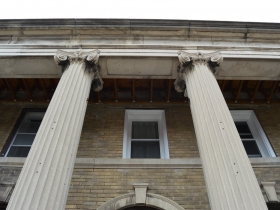

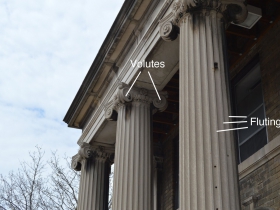

The Otto Steverwald Commercial Building (2506 W. Vliet St., built 1904) is an example of the Ionic order. There are many variations of Ionic columns, but the consistent features are the two symmetrical volutes — scroll-like ornaments that define the order’s capital. Like the Greek Doric columns on the Merchant’s Bank Building, the shafts of the Commercial Building’s six Ionic columns have been elaborated with shallow, vertical grooves called fluting, another common classical feature.

Otto Steverwald Commercial Building

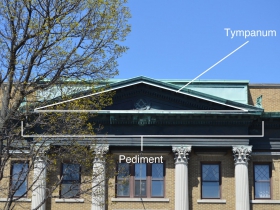

An example of fluted Corinthian columns can be seen on the Excelsior Masonic Temple (2422 W. National Ave., built 1922). Corinthian is the most elaborate Vitruvian order, and the capitals of Corinthian columns are distinguished by their use of acanthus floral motifs. Acanthus is genus of flowering plants with deeply cut leaves that are common around the Mediterranean where the classical orders originated. Also of note on the Masonic Temple is the triangular element above the portico, called a pediment. In Greek and Roman temples the pediment was the roof’s gable outlined by a sort of double cornice. The tympanum, the triangular space between the cornices, was often adorned with some sort of carved relief, in this case with the Masonic Square and Compass.

Excelsior Masonic Temple

Ancient Greek and Roman temples formed the basis not only for the orders of columns, but also the architectural framework where they would be placed. Vitruvius identified many temple layouts, all with their own names, however they are mostly variations on the three basic models I’ll discuss here.

Sherman Park State Bank (3536 W. Fond du Lac Ave., built 1927) is an example of the most basic layouts, called in antis. In an in antis temple the cella, the unarticulated solid walls that surround the main volume, are exposed on three sides and pulled forward in the front to create a portico that is enclosed on either side. In contrast the Buemming House (1012 E. Pleasant St., built 1901) is an example of prostyle, where there is still only one front portico, however it is completely open and protrudes from the cella. It’s a rarity in this city; Milwaukee has very few pure examples of these layouts. In the Sherman Park State Bank, for example, the cella wall behind the front portico has obviously been pulled forward so that it touches the columns, meaning it’s not a “true” portico like on the Buemming house. This is all part of the remixing I described earlier; architects working in the classical tradition shrunk, stretched and recombined these ancient layouts to fit the needs of their client while still being identifiably “classic.”

Sherman Park State Bank

Buemming House

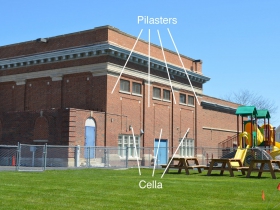

Another example of this is the North Side Natatorium (243 E. Center St., built 1908). Like the Sherman Park Bank, the architect here has pulled the cella walls up against what would be a continuous portico around the entire building, or peripteral. The architect has also mixed orders, utilizing more fully fleshed-out Ionic columns up front that then transition to Doric pilasters, flattened columns, which continue around the rest of the building all while sharing an unbroken entablature.

North Side Natatorium

Another way architects played with classical models was by adjusting the proportions and symmetries of the building’s component parts. Vitruvius gave very specific instructions for the relationship between the diameter and height for each order of columns. Tuscan, for example, was supposed to follow a ratio of 1:7 while Ionic columns were expected to be at least 1:8. Vitruvius’ proscriptions were influential; however they were not absolute. The Natatorium’s Ionic columns are around the 1:8 ratio, however the Tuscan columns of the Soldier’s Home Headquarters are closer to 1:11 or 1:12, which reflects the considerable variation also found in ancient buildings.

Proportions were also important for the intercolumniation or distance between columns. Vitruvius describes five intercolumniations all based on modules, which are one radius of the column’s shaft at the base. His ideal proportion, eustyle, can be seen in the Fred Pabst Jr. House (3112 W. Highland Blvd., built 1897) where the columns are two-and-a-quarter diameters apart. As with the proportions of columns Vitruvius’s proscriptions for the distance between them here were influential, but not absolute. St. Luke’s Emmanuel Baptist Church (2722 W. Highland Blvd., built 1913) has an intercolumniation of three-and-a-half to one, which does not correspond to any of the Vitruvian proportions. This may have something to do with advances in construction techniques and the more decorative, less practical application of columns in neoclassical buildings. While Vitruvius was concerned with aesthetics, he was also concerned with engineering and the limits of stone-on-stone masonry, which could only be spread so far.

Fred Pabst Jr. House

St. Luke’s Emmanuel Baptist Church

Those well-versed in this subject may consider my descriptions of these ten buildings as too perfunctory, but my hope is that by providing this surface-level examination of classical architecture it will be possible to begin understanding the nods and nuances of such buildings. For example, because of their simple, stout and robust nature, Tuscan columns have been closely associated with fortifications and military architecture since the renaissance, which may be why they were chosen for the Headquarters at the Old Soldiers Home, to tie the new facility into a longstanding tradition. Similarly, the eustyle columns of the Fred Pabst Jr. suggest the owner might have wanted to be seen as a cultured individual who is aware of Vitruvian proportions. When you begin to understand these architectural styles, you have the tools to better hear the fading voices of the past, and the urban experience becomes that much more rewarding.

A few of recommendations: If you want a more in-depth/academic take on classical architecture I drew heavily from Alexander Tzonis and Liane Lefaivre’s Classical Architecture: The Poetics of Order. If you want to pick up a copy of Vitruvius yourself there are many cheap additions, however, if you want one with really good commentary and illustrations I suggest a 2001 addition edited by Ingrid D. Rowland and Thomas Nobel. I also recommend Leon Krier’s The Architecture of Community. Krier is very opinionated and does not pull any punches when it comes to his distaste for modern architecture, but his theories and illustrations on the applications of classical architecture combined with his New Urbanist sensibilities is utterly engrossing, even if you come away disagreeing with him. That’s the beauty of architecture, it allows for so many opinions and so many ways to view the varied styles to be found in Milwaukee.

Milwaukee Architecture

-

A City of Theaters

Apr 19th, 2015 by Christopher Hillard

Apr 19th, 2015 by Christopher Hillard

-

The Rise of Suburban Style Homes

Mar 12th, 2015 by Christopher Hillard

Mar 12th, 2015 by Christopher Hillard

-

The First 100 Years of City Homes

Feb 25th, 2015 by Christopher Hillard

Feb 25th, 2015 by Christopher Hillard

One of the most notable examples of classical architecture is at 720 E. Wisconsin Ave. in Milwaukee.

@Barbara: True! I’ve never seen the house on Franklin Place in person, but it was amazing to learn that it’s in Milwaukee. It almost seems to have a neo-Baroque air.

@TF I’d say that is a reasonable label. The house is packed with little elaborations. I could even see it falling into Rococo, which is incredibly elaborate and, for lack of a better word, fussy.