Why So Many Bars?

A new book captures the unique social history behind Wisconsin's tavern culture.

Bottom’s Up explores these Milwaukee establishments:

His first taste of Wisconsin’s favorite beverage came 50 years ago, when the bartender, Ray Stutz asked, “What do you want?”

“A beer,” little Jim Draeger gamely replied. This was at the Beehive Tavern in Oconto, WI, a simple neighborhood bar with a mirrored mahogany backbar and chrome bar stools, upon which Draeger and his father were perched.

The bartender glanced at Draeger’s father, and then tapped off a small shorty glass with beer. It tasted terrible and bitter, but Draeger braved it down. He hadn’t quite acquired a taste for beer yet. He was just five, after all.

Having his first beer is one of the first memories in Draeger’s long love affair with the Wisconsin tavern experience and culture. Today, at age 55, Draeger is the Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer at the Wisconsin Historical Society. When the Historical Society Press asked him about authoring a book about Wisconsin taverns, he jumped at the chance and asked his friend Mark Speltz, 38, to accompany him. The pair first partnered to co-author their book Fill ‘er Up: The Glory Days of Wisconsin Gas Stations, which was published in 2008.

After pairing up and collaborating, Draeger and Speltz would spend two and a half years traveling 6,000 miles around Wisconsin scouting out the state’s most unique and historically rich taverns. The fruit of their labor is their book, Bottoms Up: A Toast to Wisconsin’s Historic Bars & Breweries, which debuted September 2012. Wisconsin Public Television produced an hour-long companion documentary for the book, which premiered Nov.12. It can also be seen for free on the WPT website.

No one knows how many bars Wisconsin has because they’re locally licensed, but the Wisconsin Tavern League has over 5,000 members. It was no easy task, but Draeger and Speltz carefully selected just 55 taverns and 15 breweries. The bars reflect geographic diversity from a range of eras and themes: biker bars, gay bars, cocktail lounges, saloons, sports bars, dive bars, fern bars, and ornate showcase bars sponsored by breweries are among them. Tips from Wisconsin residents helped them find their gems.

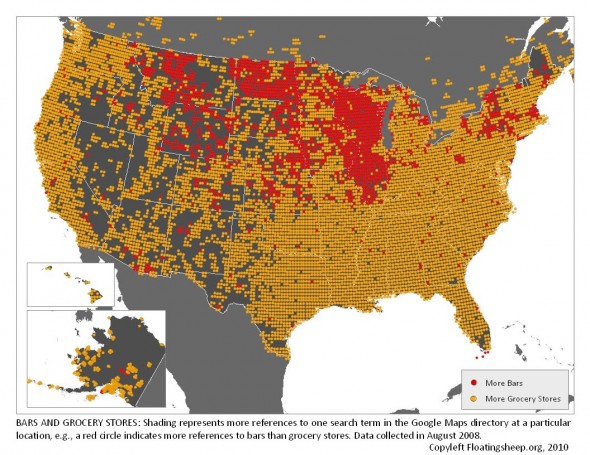

Geography blog FloatingSheep mapped the number of references to bars vs. groceries within Google Maps directory in particular locations around the U.S.

Draeger says that the focus of Bottom’s Up on the social and architectural history of taverns is unique. Most tavern books serve as guides or reviews.

“What we’re trying in the book is to explain how taverns came to be the way they are, why they look the way they do, why they work the way they do, and how that’s rooted in our historical past,” Draeger said.

Matt Filla, 43, lives in Hales Corners and does IT consulting for MillerCoors. He knows Draeger from interning at the state Historical Society during grad school. He thinks Draeger and Speltz are great at exploring “popular architecture,” as Filla puts it. In reading Fill ‘er Up, Draeger and Speltz’s first co-authored book, Filla was intrigued by the personality and stories hidden within structures as mundane as gas stations. He expects Bottoms Up will offer similar revelations about Wisconsin’s taverns.

“That’s what makes a place somewhere you want to go back to—when it’s not just a bar, but a bar with a certain personality,” Filla says. “Whether it’s a lounge or an old-school tavern, or just a place like Cheers where everybody knows your name. Because you can get a drink anywhere, you can drink at home cheaper, really.”

Draeger explains that the consumption of alcohol is not where the story ends for Wisconsin. The historical context uncovered in Bottoms Up reveals that “taverns at any given time are an expression of what people value and what they believe.”

“Here’s the interesting thing,” Draeger says. “People in Wisconsin don’t drink any more than they do in other places; they just do more of their drinking in taverns. Per capita, Wisconsin is like number six in the country for consumption of alcohol.”

Even though Wisconsin doesn’t do the most drinking in the union, the state still has the most liquor license holders. Draeger figures that because Wisconsin has historically contained a large number of breweries, it has led to an inordinate number of taverns that sell the products. He jokes that if the breweries hadn’t been in existence to compel the development of taverns in the state, Wisconsin “would be like Alabama.”

German heritage may have influenced a lively and fun-loving population, but German heritage also brought enterprising brewers to the state—Miller, Pabst, Blatz and Schlitz, to name a few—that solidified the presence of tavern culture and drinking culture. It seems that the state’s atmosphere of gemütlichkeit and the enterprising breweries, both of the past and present, enjoy a mutual benefit. Cheeseheads want to drink beer, and breweries want to brew it.

In their book, Draeger and Speltz were drawn to the theme of how breweries have thrived in Wisconsin and how they have directly influenced taverns. In the Milwaukee area, they chose to focus on Miller Brewing Co. and Pabst Brewing Co.

Draeger says that at one point, it was estimated that 85 percent of Milwaukee taverns were owned by breweries. Around 1880, the “tied-house phenomenon” began this trend of ownership. The nation’s mega-breweries were becoming fiercely competitive and it became difficult to stabilize the price of a barrel of beer. The breweries came to discover that instead of competing to sell their beer at a given tavern, they should buy and build their own taverns. Tied-houses were forced to pay their brewery’s prices and sell their brand exclusively. They were economically “tied” to the breweries. Schlitz alone owned 700 tied-houses. Many of these establishments were ornately and extravagantly designed “showcase taverns” made to establish prestige for their particular brand of beer. Breweries were so determined to eliminate competition, they were known to buy all four corner buildings on choice street intersections, according to Draeger.

Tied-houses became illegal per federal anti-trust laws after Prohibition. Ex-tied-houses are still found all over Milwaukee: Three Brothers at 2414 S Street Clair St. and Calderone Club at 842 N Old World 3rd St. are among them.

Draeger expects that years in the future, we will look back at our current era and notice the recent “renaissance of brewing,” as he describes it. He’s referring to the celebrated craft brewing trend that has spurred the development of microbreweries like Milwaukee’s Lakefront Brewery and brewpubs like the Milwaukee Ale House or Water Street Brewery. In 1978, President Jimmy Carter signed a bill that removed federal restrictions and taxation on homebrewed beer. Draeger says this act had tremendous impact on our “renaissance.” In basements and garages, creative brewers began trying old beer recipes that hadn’t been brewed in ages, and also pioneered recipes with additives like cherries or chocolate.

Randy Sprecher, founder of Milwaukee’s Sprecher Brewing Co., used to work at Pabst, but he was also a homebrewer. Craig Burge, Sprecher’s brewmaster, also started as a hobby brewer. Sprecher Brewing Co. was Milwaukee’s first microbrewery, and indeed, the first new brewery in Milwaukee since Prohibition. Homebrewing is a fast-growing hobby in the nation. President Obama is the first president to brew beer in the White House, and in September 2012, the White House released recipes for its honey ale and honey porter to the public in response to a “We the People” petition online. According the White House website, the beer is brewed with honey from the beehives on the South Lawn.

As hobby and homebrewing continue to give rise to a new era in the culture of breweries and taverns, people like Draeger and Speltz still continue their own passion of uncovering how it unfolds, connecting the historical dots.

“I don’t hunt, I don’t brew beer, and I don’t make cheese.” Speltz says. “Doing history is my hobby.”

According to Speltz, most of the cost for gas, food and lodging over the course of producing Bottoms Up was covered by him and Draeger. But both men describe their ambitious project as a labor of love. Their interest in history doesn’t stop when they come home from work every day. The duo filled nights, weekends, and early mornings with writing and research during the past few years. Speltz and his wife Kari were even committed to another labor of love during the book’s production: the birth of their daughter Marie, who is now two.

“I’m a historian because I’m a very curious person and I always want to understand why things are the way they are,” Draeger says. “It’s really about today—why things are the way they are today. And these things all have historical roots, so you tease those threads backwards in time.”

The thrill of the hunt drives and guides both historians, but they also have a thirst to share what they find, “connecting people to history, making connections that people can understand,” as Speltz puts it.

“My hope for the book is that people will understand taverns as these very special, historically rich places, as I do,” Draeger says. “Taverns are places that are full of meaning and I wanted to be able to share that meaning with other people.”

The duo continues traveling around the state for Bottoms Up events, giving talks, asking and answering questions, signing books, and sharing libations. On Dec. 6, they will be at Milwaukee’s Bryant’s Cocktail Lounge at 1579 S 9th St. Draeger and Speltz featured this quintessential cocktail lounge in both the Bottoms Up book and the documentary. In the tradition of the lounge’s founder, Bryant Sharp, the current owner invented a new cocktail of the book’s namesake, which will debut that night, accompanied by a discussion of the book.

Sharing and interacting with their fans and fellow history buffs is satisfying for Draeger and Speltz because they see their own contributions like Fill ‘er Up and Bottoms Up as a small part of the larger story.

“A book is going to last for a while, and will inspire people to do some other type of project,” Speltz says. “Doing history is just a conversation.”

-

Pressroom MKE Opening on South Side

Feb 1st, 2022 by Graham Kilmer

Feb 1st, 2022 by Graham Kilmer

-

Downtown Bar A Mixture of Jamaica and South Beach

Oct 1st, 2021 by Annie Mattea

Oct 1st, 2021 by Annie Mattea

-

WurstBar MKE Will Open On Brady Street

Sep 14th, 2021 by Annie Mattea

Sep 14th, 2021 by Annie Mattea