Waukesha Officials Tour Milwaukee Water Plant

Elected officials get up close tour of how their water will get from Lake Michigan to their taps.

The interior of the Linnwood Water Treatment Plant, filter beds are in rooms on each side of the hallway. Photo by Jeramey Jannene.

Officials from the City of Waukesha were given a tour of Milwaukee Water Works‘ (MWW) Linnwood Water Treatment Plant in advance of their city taps being hooked up to Milwaukee’s water.

A $286 million project is due to be completed in September that will connect Waukesha’s water system with Milwaukee, ending the suburb’s two-decade quest to find a replacement for its radium-laden well water.

A step-by-step tour of the secured facility, 3000 N. Lincoln Memorial Dr., gave Waukesha officials a chance to learn how Lake Michigan water is purified and what type of questions and concerns residents might have. The July 18 tour, which included Waukesha Mayor Shawn Reilly and several members of the city’s Common Council, was led by MWW Superintendent Patrick Pauly, plants manager Dan Welk and water quality operations manager Jason Otto.

The tour gave Milwaukee officials the opportunity to show off the seldom-seen plant, first built in the 1930s, and the substantial amount of behind-the-scenes infrastructure, much of it installed post-1993 cryptosporidium outbreak, that provides 100 million gallons of clean drinking water daily to the city of Milwaukee and 15 other cities.

The city-owned utility does deal with phone calls with concerns about water quality. “Usually, it’s my water smells funny,” said Otto. “You can often trace those down to really simple causes.” He noted it often ends with: “sorry, you have a really dirty sink.” But to ensure there isn’t an issue, MWW will dispatch a representative to confirm the issue if it can’t be solved over the phone. Waukesha, which will be a wholesale customer of MWW, will be responsible for providing its own customer support and billing.

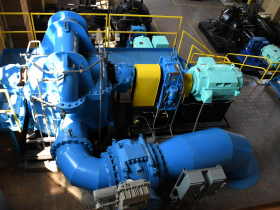

Milwaukee operates two treatment plants, the Linnwood plant in the northeastern corner of the city and the Howard Avenue Water Treatment Plant on the far south side. The 12-foot-wide intake pipe for the Linnwood plant is located 1.25 miles from shore at a depth of 65 feet, but even at that depth the water temperature can fluctuate greatly depending on the wind above. Welk, showing a graph to the audience, said temperature swings of 20 degrees in 24 hours do happen and some customers do notice it at their tap. “We have no control of that,” said Welk.

Water is treated through a dizzying 22-hour process that includes ozone disinfection, coagulation, flocculation, sedimentation, filtration, chlorine disinfection, fluoridation, the addition of a corrosion control mixture and chloramine protection before being sent into the 1,960-mile water main distribution system.

Each of the processes takes place in its own area within the sprawling plant, with the ozone facility added in response to the 1994 cryptosporidium outbreak. One of the more notable aspects of touring the plant is the lack of hands-on workers that are visible. While the utility is constantly monitoring a variety of water quality components and tweaking various parts of the process, including how much chlorine is necessary, almost all of it is run from a control room laden with large displays. “We can monitor everything,” said Arthur Fink, water plant and systems manager, noting that the Linnwood plant has visibility to the Howard Avenue plant as well as the entire distribution system. “It’s always moving. It never stops.”

Despite the challenges, Fink, Welk and several other MWW employees said the city benefits greatly from the high quality of Lake Michigan water. A host of features within the plant, including different viewing spots, are designed to show off how clear the water is.

The eight massive pumps and 32 filter beds drive home the point on just how the large the processing operation is. But MWW, citing security concerns, prohibits photos of the entirety of either component. A 3D model of the plant also demonstrates just how vast the operation is, and how much of it is underground, but photos of it are also restricted. A picture is worth 1,000 words, but you’ll have to settle for five from this reporter: It’s big and it’s impressive.

A series of pumping stations push the treated water up the lake bluff and into the distribution system. Waukesha’s water will leave the city system at S. 76th Street and W. Oklahoma Avenue, entering a 36-mile-long, 30-inch-wide pipe that a team of contractors has spent almost three years building.

The southside exit point means much of Waukesha’s water will actually be treated at the Howard Avenue plant, but each plant operates the same treatment process. The intake pipe for the inland Howard Avenue plant is located 2.5 miles from shore, a greater distance given its closer proximity to the harbor.

The Linnwood plant, besides being a more attractive Art Deco structure than the 1960s southside plant, also includes the MWW’s laboratories. It’s there that the most employees can be found, performing tasks that range from testing water quality from more than 50 monitoring points across the city to performing lead-in-water tests for customers.

The deal is expected to save Waukesha water customers $40 million over other alternatives just in up-front capital costs, and an estimated $200 per customer annually. The move will net a major new customer MWW and funding which Milwaukee intends to use to replace lead laterals. The city-owned utility currently sells water to 14 communities plus the city and the Milwaukee County Grounds. Franklin, a portion of which is already served by the utility, could join Waukesha as a new customer by 2024.

Waukesha will begin paying Milwaukee at least $3.2 million annually once the project is complete. The payments will rise to $4.5 million if Waukesha uses the full 8.2 million gallons the deal allows. Those funds will go to the city-owned water works. As part of the deal, Waukesha is also required to make a one-time payment of $2.5 million, proceeds of which will go to the city’s general fund and is intended to be used to replace lead laterals that connect private properties to city water mains. If Waukesha increases its consumption to 8.5 million daily gallons, the city will owe Milwaukee an additional $250,000 plus the increased cost of the water.

The deal, because it involves sending water out of the Great Lakes watershed, had to be approved by governors of the eight states bordering the Great Lakes as part of the 2008 Great Lakes Compact. The Waukesha deal is the first such diversion approved under the compact. Water is being returned to the Great Lakes via the Root River.

Photos

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

More about the Waukesha Water Deal

- Rate Case Likely To Result In Milwaukee Water Prices Increasing - Jeramey Jannene - Jul 24th, 2025

- After Waukesha, Will Other Communities Seek Great Lakes Water? - Danielle Kaeding - Sep 14th, 2023

- Waukesha Celebrates Completing Milwaukee Water Pipeline - Jeramey Jannene - Sep 7th, 2023

- City Of Waukesha To Begin Diverting And Returning Lake Michigan Water Under DNR Diversion Approval - Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources - Sep 5th, 2023

- Waukesha Officials Tour Milwaukee Water Plant - Jeramey Jannene - Aug 3rd, 2023

- MKE County: Board Approves Waukesha Water Deal After Revisions - Graham Kilmer - Dec 16th, 2022

- MKE County: Supervisors Stall Waukesha Drinking Water Project - Graham Kilmer - Dec 8th, 2022

- Suit Opposes Waukesha-Milwaukee Water Plan - Danielle Kaeding - Feb 8th, 2021

- Eyes on Milwaukee: Waukesha, Milwaukee Celebrate Huge Water Project - Jeramey Jannene - Nov 30th, 2020

- Metro Groundwater Has Rising Radium Levels - Danielle Kaeding - Mar 3rd, 2020

Read more about Waukesha Water Deal here