How the Amani Neighborhood Cut Crime

And improved life in 53206 ZIP code. Dominican Center and non-profits empowered residents.

A new approach to community revitalization in the Amani neighborhood is letting residents lead the way, helping cut crime and creating a successful model for working on problems at the neighborhood level.

It all started with the Building Neighborhood Capacity Program, a federal program aimed at creating the community infrastructure necessary for residents to access the resources necessary for better outcomes in safety, housing, employment and education. in 2012 Amani was one of eight neighborhoods in the nation selected by the federal government to participate in the program, and receive funding.

And like many communities that relied on industrial jobs, Amani was devastated when large employers downsized or left during the end of the 20th century. In the intervening years, Amani and the infamous 53206 zip code it sits in, became what a pair of researchers from UW-Milwaukee called a “bellwether for poverty changes in Milwaukee and nationally.”

It’s also a bellwether for the city’s racial disparities, as more than 90 percent of Amani’s residents are Black.

A 2017 Case Study of the Amani Neighborhood by COA Youth and Family Centers, stated that between 2000 and 2012 there was a significant increase in poverty, unemployment and vacant homes. Along with this, crime was a persistent problem for the neighborhood.

When the Building Neighborhood Capacity Program began in the area 2012, the Dominican Center for Women at 2470 W. Locust St. was chosen as the anchor organization. And according to Sister Patricia Rogers, its executive director, the fundamental difference between this new initiative and past efforts was this one trusted residents to know what needed fixing in their own neighborhood, and also how to fix it.

The Dominican Center acts as an intermediary between outside organizations and non-profits and funding sources and the community residents and stakeholders. “But [the residents] have to name what it is and what they want solved,” she said. “We get the other partners.”

And when you let the residents of a neighborhood lead the way, the organizations working in the community have to break down their silos and communicate better to get anything done, Rogers said. The Dominican Center has partnered with a number of organizations, like COA, LISC, Hunger Task Force, Data You Can Use, Safe and Sound, Hepatha Lutheran Church, Teens Grow Greens, and PEARLS for Teen Girls. All these organizations fit their specific services and expertise into a larger response to issues of importance to the community.

At the same time that the Dominican Center started their work through the neighborhood capacity program, COA (Children’s Outing Association) started similar work through a grant from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. The two organizations have worked as twin-pillars of “place-based change” initiatives in Amani, which involve getting all the previously mentioned organizations to work together.

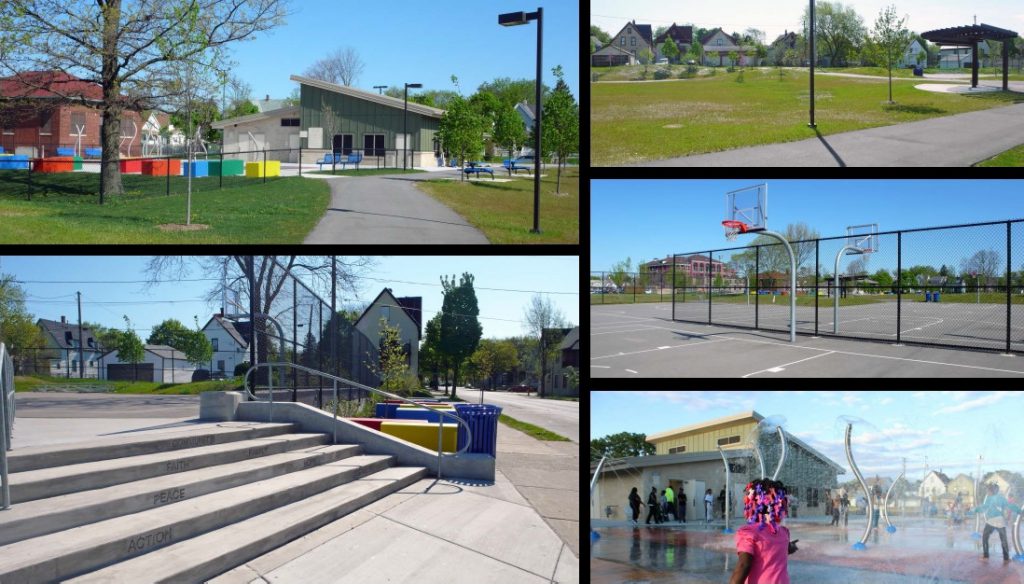

Earning the trust of the residents, who have seen social organizations and non-profits roll into the neighborhood with a certainty as to what needed to be done, took time. Rogers said it took them a whole year just to get residents to believe the project wanted them to decide what the neighborhood needed. Tackling the issue of Moody Park helped get the attention and earn the trust of neighborhood residents, she said.

The residents identified the park as an area for revitalization and the Dominican Center and other local organizations worked with stakeholders like Milwaukee County to get it done. This was proof that the organizations working in the community wanted the residents to take the lead on improving their community.

Something Rogers is very proud of is the neighborhood Block Ambassadors. These are people volunteering to work with organizations like the Dominican Center and Amani United to keep their neighbors informed of resources and where to access them, and also to provide feedback from the community to the Dominican Center and others. It’s another example of what Rogers calls helping the residents “find their own power.”

In the past, “there wasn’t a lot of love for police in this area,” Rogers said.

District Five, where Amani is located, was the center of the rash of illegal cavity searches that ultimately led to a lawsuit against the Milwaukee Police Department.

But working within this new program and new approach, the local police managed to give the residents of Amani “a different look at policing,” Rogers said. Specifically, beat cops and bike cops started interacting with residents outside of the times they were arresting one of their neighbors.

Many of Amani’s residents had mistrust for police and were afraid to call them about crime in the neighborhood, because the police had in the past been “careless in their response,” Rogers said. Nor had they interacted or engaged with residents.

That changed. Police officers started holding office hours at the Dominican Center. The bike cops, who were “so visible all the time all over the neighborhood,” started carrying flyers explaining where residents could access resources. It’s a small gesture, Rogers said, but can have a big impact.

When the police wanted to survey the neighborhood about crime and police relations, they asked the neighborhood organization if they would have their ambassadors do it. “The challenge was ‘why don’t you all do it.’ And they did,” Rogers says.” And the police came back and said ‘It’s the best thing we ever did.’”

The two back-to-back federal programs, which provided the resources for the new resident-focused efforts, have led to eight years where the crime rate in Amani has dropped faster than the rest of the city. Data You Can Use was one of the partners on the project. The organization has worked with the police department to track crime and worked with Amani United to relay that information back to residents. And the data shows that improving relations and engagement between police and residents can contribute to reductions in crime.

And in true resident-led fashion, when Data You Can Use worked with Amani United to inform the residents of the positive drops in crime occurring throughout their neighborhood, it was residents who went door to door talking about it to their neighbors, or leaving a door hanger highlighting the positive trends.

Unfortunately, one thing that hasn’t gone down is reckless driving. So the residents are tackling that next. Rogers said they recently made a batch of new signs encouraging safe driving, and next week a group of residents, young and old, are going to go out in the neighborhood and put them up.

“We’re just gonna keep going at it,” she said.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.