How A Milwaukee Mom Met The Man Who Killed Her Son

Debra Gillispie has spent two decades advocating to end gun violence, uplifting survivors’ stories.

Debra Gillispie, founder of Mothers Against Gun Violence, stands Monday, Aug. 18, 2025, in the location where her son, Kirk Patrick Bickham Jr., was shot and killed in 2003 in Milwaukee, Wis. Angela Major/WPR

Debra Gillispie tossed and turned through the night before she drove from her home in Milwaukee to a prison in Fox Lake to meet the man who shot and killed her son.

“I could not sleep,” she said.

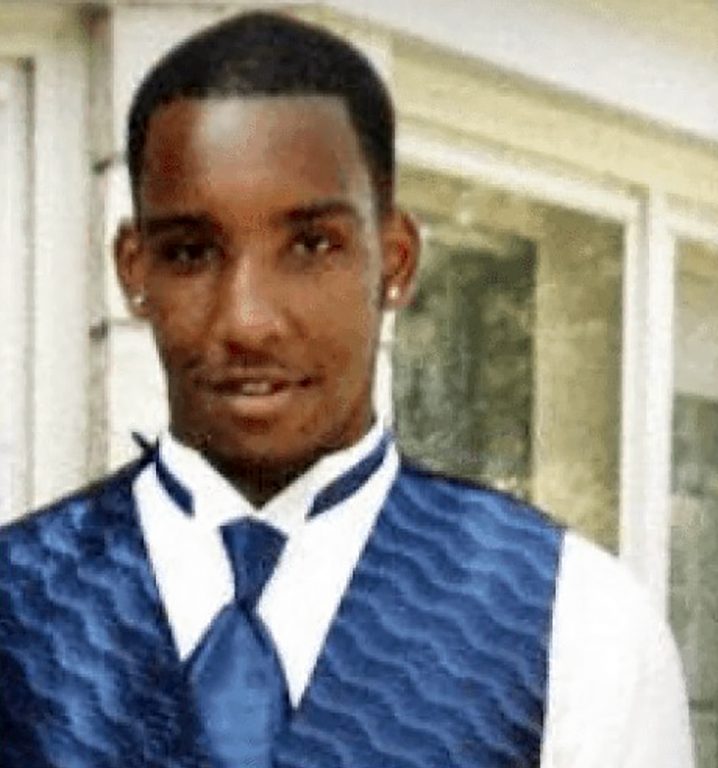

Gillispie’s son, Kirk Patrick Bickham Jr., was out celebrating with friends one night in 2003. He had just graduated from college and found a new job.

Two decades later, Gillispie made the trip to Fox Lake Correctional Institution to meet Marion. She did it with help from the Restorative Justice Project at the University of Wisconsin Law School.

“I went to see him in hopes to get answers as to what happened and why,” Gillispie said. “I also wanted to have totally forgiven him, too, because I think that’s important. Whenever you hold any animosity against someone, to be able to let it go is so much more freeing for you.”

“Whatever little bit of anything that I had was freed,” she added.

Gillispie’s journey of grief — messy, nonlinear, challenging — took her from outrage and a mission to shut down a bar, to driving across the country and back, to 20 years of leading local advocacy and reform efforts, and ultimately, to the prison that’s holding the man who killed her son.

Debra Gillispie’s son, Kirk Patrick Bickham, Jr., was shot and killed near this location in 2003 in Milwaukee, Wis. Angela Major/WPR

When anger took over

Another night Gillispie remembers not being able to sleep? The night of the shooting. When she was in bed tossing and turning, her sister called: Come quick. Something had happened to Kirk Jr.

Gillispie left in her pajamas and house shoes. She ended up outside the bar where the shooting happened. People in the crowd told her Marion was the shooter, she said. She heard he lived nearby.

So, Gillispie went looking for Marion.

“I wasn’t meant to find him,” she added.

The next day, she felt like she’d woken up from a bad dream. Gillispie wonders if, mentally, that’s what she needed to survive that moment. She felt calm, grabbed some coffee and was ready to tell her then-husband about this dream. When he hugged her and said how sorry he was, that’s when it hit her.

Gillispie’s grieving anger also went toward correcting the narrative around the shooting. She said an early news report suggested the shooting must have been gang or drug related.

“To learn that your son was murdered, and the first report you hear is that he must have been up to illegal activity. Why was that assumed?” she said. “Not only to have to experience the loss, but now having to clear his name. That was a horrifying experience for me.”

In her ire and pain, Gillispie found another target to blame: the bar. She heard the metal detectors were off that night. Had they been on, could her son be alive today? She put her energy into closing the bar. She told people what happened. She complained to the city and asked for the bar to be shut down. She was determined.

She succeeded. The bar eventually closed. But years later, she ran into its owner working at another bar near her mom’s house — and Gillispie apologized. Why?

“I do realize that I closed a Black business,” she said. “I blamed him. I was very angry and hurt. If he ever hears this, I’m sorry.”

Kirk Patrick Bickham Jr. was shot and killed in Milwaukee in 2003. Before he died, he had recently graduated from college and found a job. Photo courtesy Debra Gillispie

Channel grief into action

Gillispie realized her efforts to close the bar were misguided while she was a commercial truck driver going across the U.S. That time helped strengthen her faith. She met incredible people.

“I saw the world and how beautiful it was,” she said. “You see these reality shows and people not getting along. I assure you: The people I met, they were beautiful, regardless of their ethnicity. People were warm and welcoming.”

“After four and a half years, I did a ‘Forrest Gump.’ I stopped running,” she said. “I stopped driving, and I came home.”

After four and a half years, I did a ‘Forrest Gump.’ I stopped running,” she said. “I stopped driving, and I came home.

During a typical Friday date night with her now-husband, Gillispie saw the group Moms Demand Action was holding a meeting. She told her husband she just wanted to stop by and introduce herself.

Through that group, Gillispie met a UW-Milwaukee professor who gave her an opportunity to share the stories she collected. And so, the Voices of Gun Violence story archive was born.

Gillispie’s advocacy work also includes founding the group, Mothers Against Gun Violence. She said she pushed for responsible gun ownership legislation that called for criminal background checks for private citizen gun sales. Urban Milwaukee reported that Marion bought the gun used to kill her son at a gun show without a background check.

Gillispie also later connected with the Milwaukee County Transit System, where they started putting up interactive displays from Mothers Against Gun Violence on bus shelters around the city. Each display shows eight to 10 stories that end with messages to the community and elected officials about ways to stop gun violence, she said.

An interactive bus shelter display in Milwaukee, Wis. includes messages of remorse from perpetrators of gun violence, along with the stories of survivors. Photo courtesy of Debra Gillispie

Since 2022, Gillispie said they have put up four displays and are hoping to raise $3,200 to add a fifth. She has also shared stories in New York in 2023 through a 28-piece art exhibit, which included photo art of gun violence victim’s clothing.

In the stories she hears, she also finds healing.

“I find that their stories of resiliency are another example for me to keep going,” she said.

But with grief, there are bad days and less bad days. New moments test resiliency built up over time. In 2022, Gillispie lost her last child, her daughter Daylesha L. Bickham, to fentanyl poisoning.

After losing her son, Kirk Jr. — whom she remembered as caring, bilingual and a gentleman — she then had to carry on without her daughter, Daylesha — who was outgoing, loved animals and did voiceovers.

“That blew me away. I experienced it once. I just never thought I’d ever experience that again. To lose her, it was really hard,” she said, wiping away a tear. “I didn’t see that one coming.”

Now, she said she knows better what it’s like to not have answers, which has helped her empathize with families who have unsolved cases for their loved ones.

In August 2025, she helped put on events for National Fentanyl Prevention & Awareness Day and the second annual Survivorsfest, which was billed as “a day of hope, healing, and inspiration.”

Debra Gillispie, founder of Mothers Against Gun Violence, stands Monday, Aug. 18, 2025, in the location where her son, Kirk Patrick Bickham Jr., was shot and killed in 2003 in Milwaukee, Wis. Angela Major/WPR

‘I’ve had a full-circle moment’

In December 2024, Gillispie drove after a restless night to the Fox Lake Correctional Institution to meet the man who killed her son. When Marion walked into the room, she said he was crying.

“He was crying so bad, I got up and hugged him because I felt bad for him,” she said.

They met for about four hours. She heard his story. She found closure.

“I’ve buried my son, in my case put him to rest. The person who murdered him was captured. I’ve met him. I’ve talked to him,” she said. “I feel like I’ve had a full-circle moment.”

Gillispie was glad to have the help of the restorative justice program, but she said she wished she accepted their offer to drive her, or have someone else do it. The day drained her energy. Making the drive herself was difficult. She said as soon as she got home, she crashed.

Her advocacy work continues, though. With two decades of experience, she said she’s learned that “your goals are what has been placed on your heart.” That could involve showing up to meetings, talking to elected officials or trying to reach others with similar experiences.

“I believe that if you’re meant to do it, it will fall into place. Now it’s going to take some work,” she said. “But if you really have a calling to do it, do it.”

When Gillispie sees others feel empowered in sharing their voices, she feels grateful that her own loss has found a purpose.

She offered advice to those who have lost loved ones.

“Acknowledge the pain. Acknowledge the loss. Find someone to talk to,” she said. “Don’t be afraid to talk about the loved one that you lost. Do it as often as you need to.”

“Wisconsin Life” is a co-production of Wisconsin Public Radio and PBS Wisconsin. The project celebrates what makes the state unique through the diverse stories of its people, places, history and culture. Broadcast audio for “Freezing but warm,” “Blind,” and “L’etoile danse (Pt.1),” by Meydän and courtesy the Free Music Archive (CC BY)

Milwaukee mom’s grief leads her to meeting the man who killed her son was originally published by Wisconsin Public Radio.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.