The Surprising Views of Justice Hagedorn

Elected as a conservative, he actually sides at least as much with liberals.

Brian Hagedorn. Photo courtesy of the Friends of Brian Hagedorn.

When he ran for, and narrowly won, a seat on the Wisconsin Supreme Court, it was widely assumed that Brian Keith Hagedorn would comfortably join the court’s dominant conservative court majority. This, after all, was someone who was for years a loyal soldier in the conservative movement.

At Northwestern University where he received his J.D. degree in 2006, Hagedorn was president of the school’s chapter of the conservative Federalist Society. Following graduation and a stint at Foley & Lardner, in 2009 he was appointed as a law clerk to conservative Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice Michael Gableman. In 2010, Hagedorn was an Assistant Attorney General in the Wisconsin Department of Justice, under Republican Attorney General J. B. Van Hollen.

In December 2010 Hagedorn was appointed chief legal counsel to Republican governor-elect Scott Walker. He remained in that office through July 2015. As chief legal counsel, Hagedorn was a drafter of Walker’s controversial Wisconsin Budget Repair Bill of 2011, which restricted the power of Wisconsin’s public employee unions. In 2015, Walker appointed Hagedorn to District II of the Wisconsin Court of Appeals, based in Waukesha.

In 2019, Hagedorn ran for a seat on the Wisconsin Supreme Court. His opponent, Lisa Neubauer, was his colleague, also serving on District II of the Court of Appeals. Neubauer was widely supported by liberals, Hagedorn by conservatives.

Despite this, a 2019 analysis by Marquette history professor Alan Ball found remarkably little difference in the two judges’ voting records: “As the election approaches,” he wrote, “political advertisements on television and other forms of commentary have described the two candidates as occupying starkly different ideological positions. Consequently, one might also expect that their time on the Court of Appeals would be marked by frequent divergence … But such has not been the case.”

Ball went on to list several examples of agreement. For example, in 274 cases in which the two judges served on the same panels, only in 5 (2%) did either judge dissent. Moreover, Ball noted, Hagedorn’s “handful of dissents are not nearly as fervent or bitter as those encountered on the Supreme Court.” Indeed, in dissenting Hagedorn often expressed sympathy for the majority’s position, Ball found.

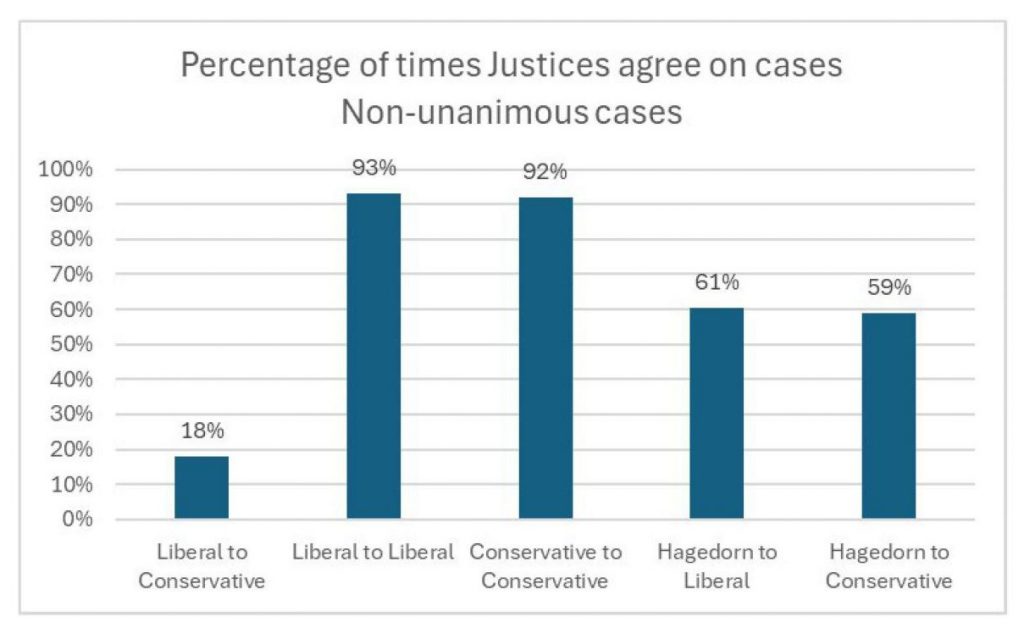

Since being elected to the Wisconsin Supreme Court, now-Justice Hagedorn seems to follow the same pattern, as later research by Professor Ball suggests. He did a chart showing the percentage of cases in which each justice agreed with each other justice during the term just ended. Using Ball’s data, I calculated the combined percentage of members of three groups: the four liberals, the two conservatives and Hagedorn, to create the next chart. For example, liberals agreed with conservatives in an average of 18% of the cases. Members of the liberal and conservative groups agreed with other members over 90% of the time. Justice Hagedorn is the exception to this pattern. On average, he agreed with members of the two groups around 60% of the time.

Percentage of times justices agree on non-unanimous cases.

A look at two cases decided in the recent term illustrate this pattern. The first, called Tony Evers v. Howard Marklein, is one of several which challenge provisions in Wisconsin laws that allow legislative committees to block actions of the executive.

The Evers v. Marklein case started two years ago when Governor Evers and several of his agencies challenged provisions in Wisconsin law that gave legislative committees the ability to block actions by several of these state agencies. Initially the Supreme Court chose to consider only one of these, the ability of the Department Natural Resources to purchase land for its conservation through the Nelson-Knowles program. Eventually the court ruled against the law giving a legislative committee a veto power over conservation purchases.

That, however, left several issues that were challenged in Marklein but not considered by the court. The first was an administrative rule from the Marriage and Family Therapy, Professional Counseling, and Social Work Examining Board. It would ban so-called conversion therapy” that attempts to change a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity. The rule would have classified it as “unprofessional conduct.”

The legislative committee blocked this rule and another rule by the Evers administration intended to update the Wisconsin Commercial Building Code.

A majority of the Court voted against the laws giving the legislature a veto over rules proposed by the executive in implementing the law. Justice Karofsky delivered the majority opinion which Justices Ann Walsh Bradley, Dallet, and Protasiewicz joined. Justices Ziegler and Rebecca Grassl Bradley filed dissenting opinions.

Justice Hagedorn filed an opinion “concurring in part and dissenting in part.” What does he mean by that? My interpretation is that he is fine with what the court majority decided, that the legislative committee had abused its power, but doesn’t like how it arrived at its decision. In his view the court should have considered and incorporated in its decision the ongoing controversy—mostly on the right—as to whether rulemaking by the executive is borrowed from legislature.

In a quite lengthy footnote, he lists some of the major players in this controversy:

- City of Arlington, Tex. v. F.C.C in which Federal Justice Scalia, writing for the court, arguing against Chief Justice Roberts’s dissent, whereby the Chief Justice called rulemaking an exercise of legislative power and Justice Scalia states that it is an exercise of executive power

- Philip Hamburger, Is Administrative Law Unlawful? stating that a “subdelegation problem . . . arises primarily where Congress authorizes others to make legally binding rules, for this binding rulemaking, by its nature and by constitutional grant, is legislative.”

- Eric A. Posner & Adrian Vermeule, Interring the Nondelegation Doctrine, arguing that “a statutory grant of authority to the executive branch or other agents can never amount to a delegation of legislative power. A statutory grant of authority to the executive isn’t a transfer of legislative power, but an exercise of legislative power. Conversely, agents acting within the terms of such a statutory grant are exercising executive power, not legislative power.”

Two very different views about the relationship between the executive and legislator are evident in the list above. One view is that rules developed by the executive reflect a delegation from the legislature. One problem with this view is that it encourages the legislature to always keep control over the rules. We see the results of this view in Wisconsin.

The other view is that the job of the legislature is to make laws. Once a bill is passed using “bicameralism and presentment,” meaning a majority vote in both houses and adoption by the executive, the legislature’ s job was done. If members of the legislature disapprove of the executive’s implementation, their solution is a new law.

The latter view is what the Wisconsin Supreme Court approved and Hagedorn appears to agree. It’s just the latest example of Hagedorn siding at least as often with the liberal justices as with the conservatives. He has proved a far more interesting and unpredictable justice than one might expect from his background.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

Just consider how much could be accomplished if the legislative branch of the state government performed like this.