Did Schimel Get Too Partisan in Election?

The conservative in race for state superintendent was less strident and did better.

Looking back at the April election, did Brad Schimel sabotage his candidacy?

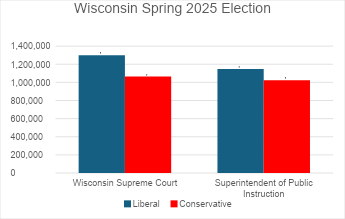

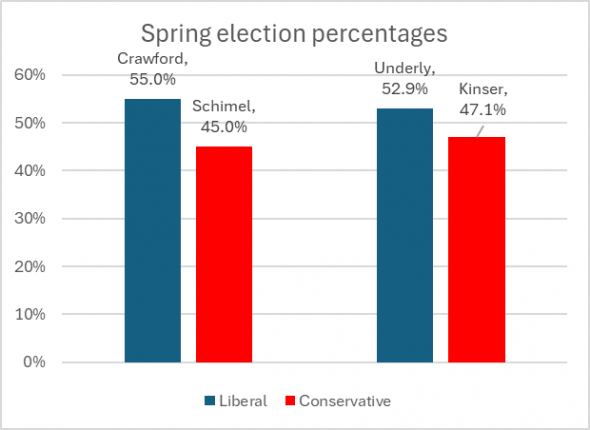

The next graph shows the (unofficial) results of April 1 election. In the election for Supreme Court justice, Susan Crawford easily defeated Brad Schimel by ten percentage points. The race for Superintendent of Public Instruction was much closer. The incumbent, Jill Underly managed to retain her office. Almost 200,000 of the 2.4 million people who voted for one of the Supreme Court candidates skipped the superintendent election.

In the next graph, the votes have been converted into percentages. Put this way it’s clear that the race for the head of DPI looks much more competitive than that for the Supreme Court, with a gap of 5.8 percentage points between Underly and Brittany Kinser. That compares to a gap of ten percentage points between the two candidates for Supreme Court.

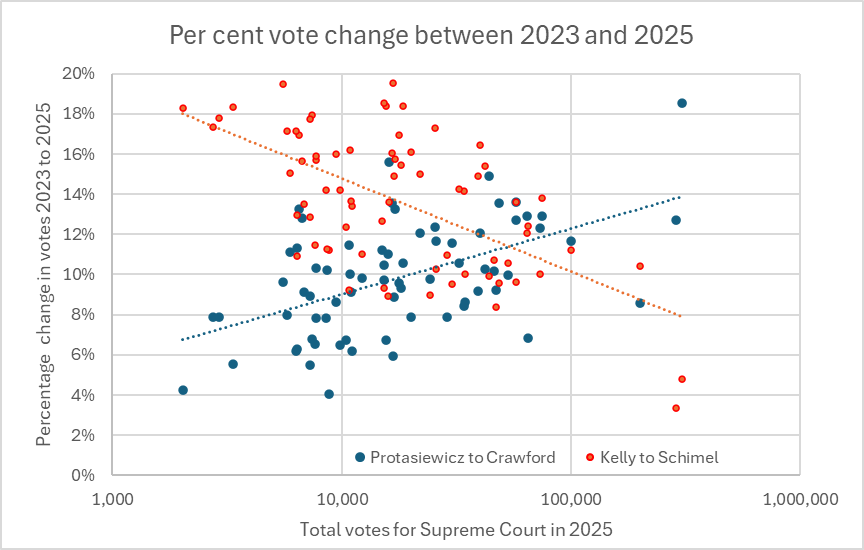

The next graph plots the changes by county between the Supreme Court elections in 2023 and 2025. Each dot represents the percent change in the vote for the liberal candidate in blue and for the conservative candidate in red.

In every county, no matter how small or large, both the liberal and the conservative vote grew between 2023 and 2025. Thus, in every county Crawford had more votes than Janet Protasiewicz, the liberal candidate in 2023. Likewise, Schimel had more votes than Daniel Kelly, the conservative candidate in 2023. The increase in voting was widely spread, varying from about 4% to 20%.

Yet the size of the counties does have an effect on voting. This is shown by the two trend lines in the graph. The blue (liberal) dashed trend line slopes upward. This indicates that as the county voting population increases (think Dane County), the magnitude of the percentage increase in the liberal vote gets larger.

With conservative voting, there is also a size effect, but it works in the opposite direction. The percentage margin for the conservative candidate decreases as overall population increases. The more rural and sparsely populated a county, the higher the percentage vote for the conservative candidate. As population increases in conservative-leaning counties, the conservative margin goes down.

The graph shows that not only are small counties more conservative and larger counties more liberal on average, but that between 2023 and 2025 in Wisconsin they have become even more so.

In the days since the election, a number of explanations for Schimel’s loss have been advanced. One is to point to changes in the demographics of the two parties. In recent years, the Democratic Party has come to be the party for people with college degrees. Perhaps people with college degrees are more likely to regard the Supreme Court as important.

Related to this is the suggestion that the Republican Party has gained more casual voters who are more likely to turn out for presidential elections, particularly if Trump is a candidate, than for down-ballot elections.

Another possible explanation is that Schimel suffered from the election cycle effect. In this scenario, the losers in one election—in this case last November’s presidential election—are more likely to be motivated by a desire for revenge in the next election and turn out and vote.

In addition to these possible explanations for Schimel’s poor showing, he may have sabotaged himself with his ongoing closeness to Donald Trump and Elon Musk. In response to Crawford’s comment that Schimel aimed to be part of Trump’s support network, PolitiFact rated her comment “Mostly true.” It concluded that “although Schimel does not come straight out and say he wanted to be part of a Trump support network, his public pronouncements and campaign literature clearly indicate his affinity for a Trump support network.”

One of the two most common themes that opponents of a Supreme Court candidate level against the opposing candidate is that he or she has already made up his or her mind about an issue, before hearing the arguments and reading the briefs. Often a candidate’s past statements about issues are used to make this point. But Schimel’s very public expressions of affinity towards Trump during the campaign took the argument about judicial prejudice even further. If Schimel had been elected to the Supreme Court, parties to a case involving Trump or Trump’s government would have to be concerned about the independence of him. That may have helped Crawford in this election.

The outcome of the election of the Superintendent of Public Instruction can be taken as further evidence that Schimel sabotaged his candidacy by his public embrace of Trump. Compared to the race for Supreme Court, the race for SPI was a very quiet one, but much more competitive. Nominally, Kinser had the support of the Republican Party, but that support was not very evident. And she came closer to winning. Perhaps being quiet can be an advantage.

Correction: The story has been updated to correct the winning percentages for the race for DPI, making the gap 5.8% instead of 2%. Additionally, the number of voters who voted in the Supreme Court race but didn’t vote in the DPI race was update from about 360,000 to almost 200,000.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

Data Wonk

-

Life Expectancy in Wisconsin vs. Other States

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Republicans Opened the Door To Redistricting

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Connection Between Life Expectancy, Poverty and Partisanship

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

It appears like you’re missing around 100,000 votes in the DPI race, it was nearly a 6 point race, not 2.

Schimel’s reliance on his affinity to Trump insured his loss. We have one too many lunatics in office since the presidential election.

Interesting article and approach, but Thompson may be missing the elephant in the room: Abortion.. This is an issue that Republicans have been unable to formulate a reasonable position.: Women want the have the right to make their own health care decisions, at least in the first two trimester as originally delineated in Roe V Wade.

Nate Monty is right. A corrected version is on its way.