Vaccine Fatigue Causing People to Skip Shots, Wisconsin Experts Say

Only 34% of Wisconsinites got a flu shot this season.

A health care worker places a bandage on a child after giving a vaccination shot. (Scott Housley | CDC)

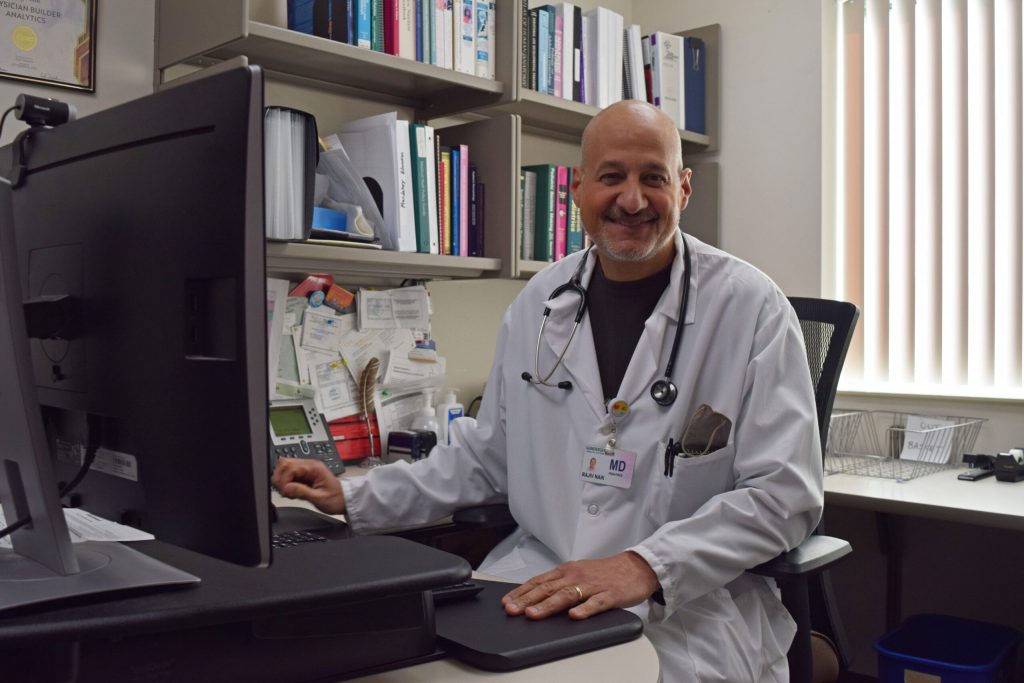

Dr. Raj Naik has been a pediatrician in the La Crosse area for more than 25 years. This year’s flu season is one of the worst he’s seen.

Influenza has hospitalized more than 6,500 Wisconsinites since Sept. 1, according to state Department of Health Services data, and the virus is still spreading at a high rate in the northcentral part of the state. There were a total of 3,901 flu hospitalizations in the state during last year’s flu season, which typically runs from October to May.

Primary care providers are worried not only about how the decline affects immunity to the seasonal disease, but also what it says about changing attitudes towards vaccines in general. Naik, who works at Emplify Health by Gundersen, said it’s becoming more and more common for a family to arrive at his office unwilling or uninterested in talking about vaccines.

“It’s not usually hard to pick up on the fact that there is some fatigue or even resistance to the discussion, both from verbal and nonverbal communication,” he said.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, mistrust of vaccines has risen to national attention in new ways. President Donald Trump’s administration appears to be continuing the trend. Longtime vaccine critic Robert F. Kennedy Jr. now leads the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. In February, the Food and Drug Administration canceled without explanation an annual meeting focused on preparing next year’s flu shot.

But Naik and other Wisconsin health experts say anti-vaccine sentiment is not the only reason fewer people are getting the shots. They say patients’ apathy, both toward vaccines and the seriousness of diseases like flu, is just as serious a threat to public health.

Dr. Raj Naik, pediatrician at Emplify Health by Gundersen, said talking to patients and their families about vaccines has become more complicated since the COVID-19 pandemic. Hope Kirwan/WPR

Pandemic aftermath changed trajectory of flu shot uptake

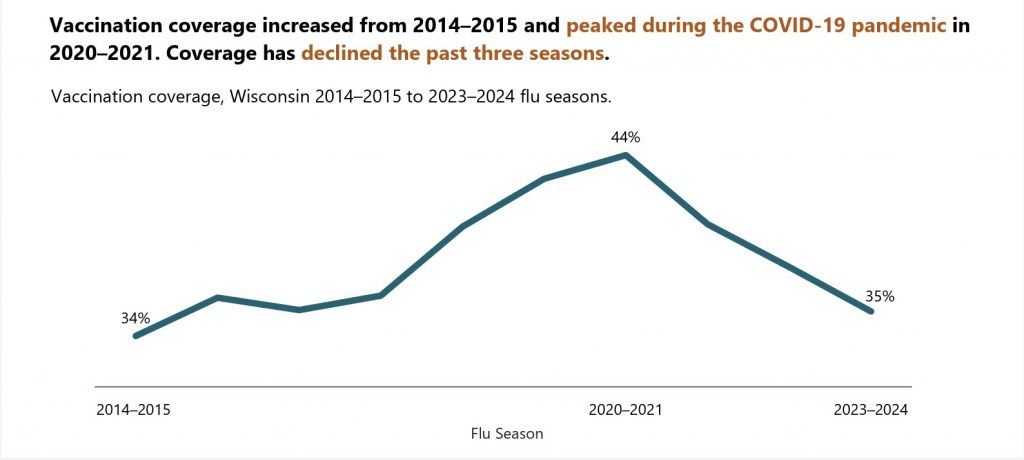

Data shows the COVID-19 pandemic was a clear turning point for uptake of the seasonal flu shot in Wisconsin. After years of growth in flu shot rates, they have rapidly fallen each year since 2020.

For years, vaccination rates had been on the rise, going from 34 percent during the 2014-15 respiratory illness season to 42 percent for the season starting in 2019.

Heading into flu season in late 2020, state and federal health officials focused on very specific messaging around the influenza vaccine, according to Ajay Sethi, director of the Masters of Public Health program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. They wanted to prevent a “twindemic” that would involve both COVID-19 and flu infections spreading unchecked.

“It was about protecting our health care system,” Sethi said. “They were expecting, potentially, an overload of patients with COVID, so (the message was): Let’s at least spare hospitals patients with flu.”

Pharmacy student Joe Crahan gives a COVID-19 vaccine to a newly eligible child Wednesday, June 22, 2022, at Fitchburg Family Pharmacy in Fitchburg, Wis. Angela Major/WPR

Sethi said public fears about the new disease and hospital capacity meant that message worked. Nearly 44 percent of Wisconsinites got a flu shot that season, the highest percentage in recent record. Only 28 residents in the entire state were hospitalized with influenza that winter.

But the united effort behind vaccination started to deteriorate as the pandemic went on. Sethi said the country went through several mild seasons of influenza, with hospitalizations and deaths remaining relatively low despite declining vaccination rates. Instead of inspiring continued vaccination, it fed the perennial idea that influenza is not a real public health threat.

“There just wasn’t enough flu to reinforce why the flu vaccine is important,” he said.

A DHS report from August 2024 shows the previously growing influenza vaccination rate started steeply declining after the 2020-2021 flu season. Chart courtesy of DHS

The pandemic also amplified the message of people who mistrust vaccines and the public health officials promoting them. Naik said over the last decade, questions about the safety of many vaccines have become more common online. The rapid and public development of the COVID-19 vaccine created an opportunity for those theories to move from the fringe to mainstream discussion.

“Anybody can get information, but not all of it is good information,” Naik said. “It’s made the entire conversation about not only vaccines, but science in general, more complex.”

While treating hospitalized children for influenza this winter, Conway said most of the families he encountered weren’t opposed to the flu shot. They just hadn’t made getting one a priority this winter.

“I kept hearing the same thing over and over again,” he said. “‘We usually get the flu shot every year, we just happened to miss it this year.’ Or, ‘We were catching up on our other vaccines and figured we could wait and get that one later.’”

A national survey by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention last June asked adults why they chose not to get the flu shot during the 2023-2024 season. One in five people said their main reason was because they weren’t concerned about getting sick.

The second most popular response, at 15.5 percent, was they had chosen not to get any vaccines last year. Nearly 11 percent of respondents said they didn’t have time or just didn’t get around to getting the shot.

Both patients, providers are tired of fighting about vaccines

Even before the pandemic, Conway said, patients and providers have treated the seasonal flu shot differently from other vaccinations.

It’s effective at preventing severe disease, but it doesn’t stop all infections. Influenza can also be mild, or mixed up with other seasonal respiratory illnesses, which leads people to perceive the flu as a seasonal annoyance rather than a vaccine-preventable disease.

Like many diseases, flu is most dangerous for older adults, young children and people with health conditions like asthma or heart disease. While the disease is more severe than a common cold, including fever and body aches, most people are able to recover at home without medical treatment. But serious complications related to flu can happen at any age, including inflammation of the heart, brain and muscle tissue.

“Patients have it because they feel like we’re constantly telling them, ‘You need more vaccines,’” Conway said. “And the providers are like, ‘I’m really tired of fighting with people.’”

Many providers are focused on making a strong recommendation for routine immunizations for diseases like measles and whooping cough, Conway said. And that means they’re more likely to give patients a pass on seasonal boosters for flu and COVID-19.

Encouraging seasonal vaccinations each winter has also become a more complicated message because of the addition of the COVID-19 shot and the vaccine against respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV. Last winter was the first time all three vaccines were offered simultaneously.

Sethi said the recommendations end up competing when flu season starts, prompting questions about how many shots a person can get at one time and whether a booster is needed if you’ve recently had a disease like COVID-19.

“All of that is good conversation, but it does have this unintended effect of not getting the vaccine now,” he said. “Any delay might end up causing people to never get it, especially as the months roll around and you see people around you with flu and you feel just fine.”

Providers, public health officials face challenges in correct course on vaccines

Sethi said this year’s severe flu season may prompt more people to take action next year, especially for those who had a loved one hospitalized with influenza.

The cost of low vaccination rates has also been on display in Texas and surrounding states, where an outbreak of measles has spread to more than 300 people and killed two individuals since the start of the year. The outbreak has mainly affected unvaccinated children in rural counties.

But achieving a broader change in public attitude toward vaccination may be more difficult because of declining support at the federal level.

During the first month of the Trump administration, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention abruptly pulled the webpage for its “Wild to Mild” campaign which encouraged the flu shot. During his U.S. Senate confirmation hearing, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. said he supports vaccinations. But Kennedy still refused to acknowledge scientific evidence that childhood immunizations like the one for measles are safe and are not linked to autism.

“I’m hopeful that we can still use that channel of communication to help individuals make good decisions, even if there’s lots of noise coming at the top,” he said. “It’s devastating, frankly. But at the same time, it’s about the work. And we have to just think about: How can we help people make good health decisions in an environment where not everybody’s on board?”

Conway believes this change needs to start in providers’ own attitudes. He said the medical community needs to treat seasonal flu and COVID-19 shots as routine practices, what’s called the presumptive approach in medicine.

“It works in all sorts of different health behavior things, whether it’s you needing to get your colonoscopy or getting screened for your mammogram,” he said. “If the norm is a provider is expecting their patients to get these, and if the norm is we’re all proud of the fact that we got these, that very loud minority of people not getting them becomes just a voice in the forest, rather than the loudest voice in the room.”

He said electronic medical records can help make sure patients are getting these prompts, and could even be used to identify those with higher risks and who could most benefit from getting the shots.

The presumptive approach is one of the ways Naik tries to encourage vaccinations among the families he treats in western Wisconsin. But since the pandemic, Naik said he has also become more focused on his relationship with his patients. That might mean respecting their decision to decline a shot, with the hope that one day they’ll be more receptive to his recommendation.

“Part of building that trust is not only expecting people to trust you, but you actually have to give trust,” he said. “You’re going to have to trust that families want to do the right thing and want to make the best decision for their child or for themselves.”

Vaccine fatigue is causing people to skip recommended shots, Wisconsin experts say was originally published by Wisconsin Public Radio.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.