Made in Milwaukee

How three Milwaukee water-tech businesses are innovating global sustainability solutions.

Rapid Radicals principals Will Schanen, Paige Peters, and Dylan Waldhuetter speak at an August 2023 press conference with their Torrent3 modular treatment unit at MMSD’s State Street property for testing. Photo by Michael Timm.

Three little-known Milwaukee companies that received business accelerator support from The Water Council are playing a role innovating solutions to global water sustainability problems.

The stories of Rapid Radicals Technology, Wellntel, and P4 Infrastructure illustrate ways that Milwaukee water-tech startups survived to make their first ripples in the marketplace.

Problem 1: sewer overflows during heavy rains violate regulatory requirements and contribute contaminants to surface water.

Rapid Radicals’ solution: a scalable catalyst to speed up ozone-based wastewater treatment at overflow locations.

Rapid Radicals’ Torrent3 system fits within a 45-foot-long shipping container. Inside, wastewater is routed through a solids filter and then three tanks where ozone is injected with a proprietary catalyst to treat the effluent to meet permit criteria. Deploying multiple systems at overflow locations is intended to alleviate pressure on wastewater treatment facilities during heavy rains.

But company principals say their technology can also be adapted to augment existing treatment facility capacity, used for military or disaster-response situations as a mobile water treatment unit, or serve industrial clients with specific regulatory needs — for instance to manage PFAS or other contaminants.

Led by Dr. Paige Peters, founder and chief technology officer, CEO Dylan Waldhuetter, and chief operating officer Will Schanen, the young company has matured through a decade of research and development to the brink of commercialization.

Peters traces the company’s origin story to the torrential July 2010 storm that triggered overflows and flooded basements across Milwaukee — including the basement of Dr. Daniel Zitomer, Marquette University’s Water Quality Center director and then her academic mentor. It led the pair to explore how to speed up ozone treatment to help manage overflows.

A series of ozonation tanks inside Rapid Radicals’ Torrent3 containerized system. Photo by Michael Timm.

Less commonly used for wastewater treatment, ozone is more commonly used to treat drinking water. After Milwaukee’s 1993 Cryptosporidium episode caused the largest waterborne disease outbreak in U.S. history, for instance, Milwaukee Water Works added ozone treatment — a major reason Milwaukee’s drinking water is now considered among the cleanest in the world.

But ozone treatment needs time and space. During a sewage overflow both are at a premium.

Starting in 2014 with support from the National Science Foundation (NSF), Peters and Zitomer developed a catalyst that worked in the lab. Over the years as a graduate student, Peters persisted in scaling up the technology.

The result reduces treatment times that would take half a day using conventional biological methods to just half an hour.

“Rapid Radicals’ patent-pending catalytically enhanced advanced oxidation process can treat wastewater to the same quality or greater than conventional treatment 20 times faster in 95% less space,” according to its successful 2024 grant application to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), one of multiple federal grants supporting the business.

NSF provided two phases of “America’s Seed Fund” Small Business Innovation Research grants, totaling over a million dollars. The NOAA grant is supporting AI-assisted work to further reduce treatment times.

The Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District (MMSD) has also been a key partner. From 2020 to 2022, MMSD South Shore hosted Rapid Radicals’ containerized pilot system. In 2023 MMSD hosted a second scaled-up containerized system at its State Street property near the Menomonee River. In 2024, both systems were at MMSD South Shore, being used for further testing and process improvement.

Founded in 2016 as an LLC, the company converted to a Delaware-based corporation in 2023, when it also celebrated a technology transfer agreement with Marquette University. Rapid Radicals has an office at 247 Freshwater — the Walker’s Point building formerly called the Global Water Center.

Rapid Radicals’ system is also participating in an NSF-funded Great Lakes ReNEW “Waste to Wealth” regional resiliency engine based from Chicago. That work is intended to improve energy efficiency using automation and custom sensors responsive to wastewater composition.

Rapid Radicals is collaborating with Aqua-Aerobic Systems, Inc. (AASI), an advanced water treatment technology company based near Rockford, Ill., itself part of Metawater, based in Japan.

The Torrent3 system combines the two companies’ technologies, Peters said, combining AASI’s AquaStorm cloth media filtration technology for solids removal with Rapid Radicals’ chemical oxidation process to achieve high-rate, wet-weather treatment.

“As we move the technology into the commercialization phase, we’re excited by the advancement of Rapid Radicals and AASI’s technologies to solve big problems with bold solutions,” Peters said.

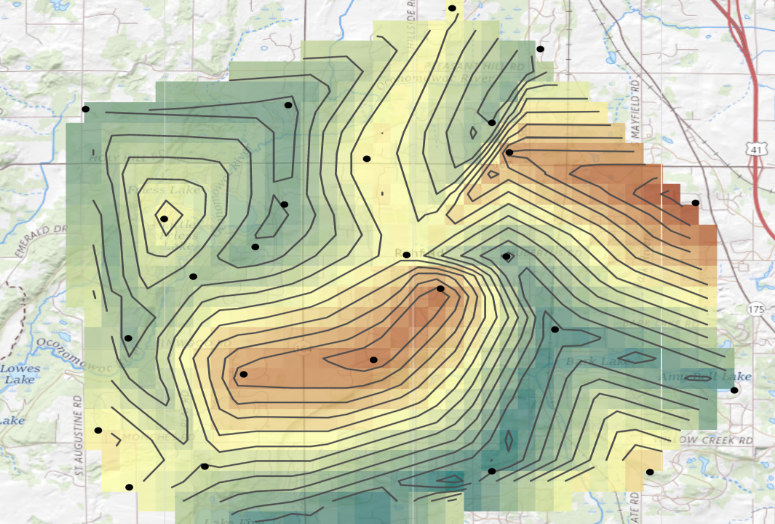

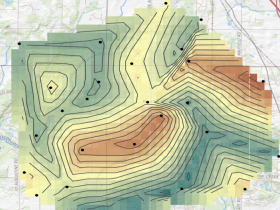

One-year groundwater level change contour map: green/blue higher groundwater, brown/orange lower groundwater. Image courtesy Wellntel.

Problem 2: as an invisible resource, groundwater is challenging to manage, especially as climate change stresses water-use patterns.

Wellntel’s solution: subscription-based groundwater monitoring and cloud-based analytics to guide resource managers.

The company’s acoustic sensors can be deployed into networks of existing wells without relying on drilling expensive dedicated monitoring wells, said Marian Singer, Wellntel CEO and co-founder with Nicholas Hayes.

Wellntel began operations in 2013, and spent three years developing the acoustic sensors which are deployed at the top of existing wells, measure water levels using sound, and transmit data via radio to an internet node connected to the cloud.

Based out of a Hamilton Street office on Milwaukee’s East Side, Wellntel’s eight-person team serves clients ranging from Napa Valley vineyards and Wisconsin dairies to groundwater conservation districts throughout the state of Texas.

Closer to home, the Village of Richfield deploys a Wellntel groundwater monitoring system that guides its growth plan, helping to inform lot sizes and coordinate with nearby Germantown, said Singer.

Milwaukee sources its drinking water from Lake Michigan but most of Wisconsin draws drinking water from groundwater wells — and Singer points to the fact that there are over 16 million existing wells throughout the United States as Wellntel’s “aha moment.”

“The bulk of our business is in the places where groundwater is really critical and also either managed or becoming a managed resource,” Singer said. “So: California, Texas, New Mexico, Oregon, Indiana, Florida, South Carolina — places that are thinking about their water supply and how it’s changing, and how they continue to ensure that down the road there is water.”

In November 2024 Wellntel added as a client a water utility in Thessaloniki, Greece serving about 320,000 people. Talks were ongoing with potential clients in Mexico.

One of two porous alleys in Cudahy, Wis. using PaveDrain pavers and P4 Infrastructure’s instruments. Photo by Michael Timm.

Problem 3: water-quality benefits of green stormwater infrastructure are estimated from design specifications rather than measured from how it works in the field.

P4 Infrastructure’s solution: monitoring systems that measure function to inform water-quality parameters and maintenance considerations for green stormwater management practices.

Chris Foley, a civil engineer with years of experience including at Marquette University, in 2017 teamed with two other engineers, Joe Diekfuss and Nick Hornyak, to form P4 – shorthand for “products for public-private partnerships.”

Headquartered in a Brown Deer facility off 51st Street, the company builds monitoring systems for green stormwater infrastructure that integrate sensors measuring soil moisture, water levels, precipitation, velocity and flow. Clients access their data via digital dashboards.

One client is the City of Cudahy, where a pair of unassuming alleys – off Squire and Van Norman avenues – have been at the frontier of green stormwater infrastructure instrumentation since 2019.

That’s because each contains a P4 instrument block that records and sends data about how water is managed below the alleys’ porous paver blocks designed by another company, PaveDrain.

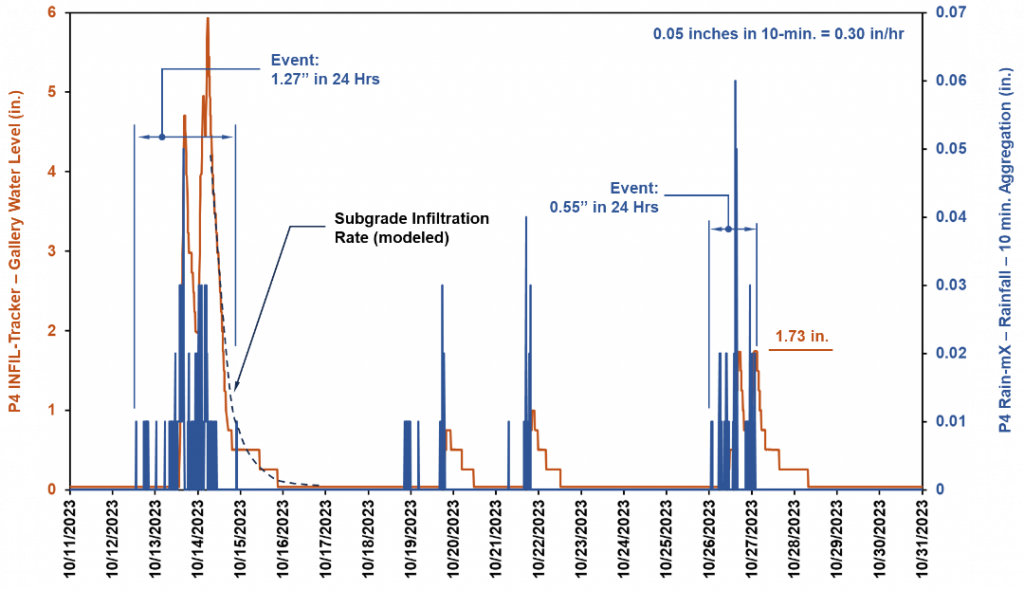

Data visualized from a porous alley in Cudahy showing four rain events (blue lines) and measuring the subterranean stone gallery water level in October 2023 (orange lines). Water moved rapidly through the gallery beneath the alley’s porous pavers, infiltrating into the ground below. All the stormwater runoff was returned to the ground, managing 100% of solids and phosphorus. Courtesy P4 Infrastructure.

A skeptical glance at the organic debris pressed into cracks between the alley’s pavers — where water is meant to infiltrate — raises concerns about clogging.

But three years of monitoring data tell a different story. When it rains, the water finds a way down.

“[When] you start to look at the performance of these systems with time, we find they perform better than you thought,” Foley said.

P4 has deployed over 60 systems throughout the United States including a network of sensors in Peoria, Ill.

“Every time we instrument one of these pavements, that is data that can stitch together the behavior of a watershed,” Foley said.

This has implications for municipal governments and property owners seeking state credits for using green infrastructure to reduce pollution contributed to their watersheds.

Wisconsin’s current guidance for porous pavement as a stormwater management practice provides a filtering credit of 65% removal for total suspended solids and 35% removal for total phosphorus, but 100% removal credit for the volume of water infiltrated.

On paper, Cudahy’s porous alleys would only qualify for the partial credits. But measurement revealed that all the water managed by the alleys actually infiltrates into the ground below due to an incorrect assumption about the subgrade porosity. That means the alleys should qualify for full credit for removing all the pollutants.

“So, let’s start designing according to the way [green infrastructure systems] behave,” Foley said. “But you never get there until you start measuring. So, we hope to provide people better design tools.”

Locally, a P4 system monitors a bioretention basin at MSOE’s Viets Plaza. P4 also installed a solar-powered rain gauge and sensor that monitors the water level of an underground cistern draining four bioswales at Green Tech Station, a green infrastructure research and demonstration site near 31st and Capitol on Milwaukee’s northwest side. Monitoring the cistern water level helped project partners to troubleshoot a leak in 2023.

Reflo leads a student tour at Green Tech Station. Porous media types are installed in the test bed plaza, which overlies an underground cistern. P4 provided a solar-powered rain gauge. Photo courtesy of Reflo.

Photos from Wellntel

Photos from Michael Timm

Writer Michael Timm is a Milwaukee Water Storyteller for the nonprofit Reflo.

This project is funded by the Wisconsin Department of Administration, Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration under the terms and conditions of Wisconsin Coastal Management Program Grant Agreement No. AD239125-024.21. Funded by the Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office for Coastal Management under the Coastal Zone Management Act, Grant # NA22NOS4190085

Excellent! Great implementation of a great idea!

Regarding the mobile units – Do they have/use

apparatus that siphons from sewers in overrun-prone areas?

Or do they treat only water that has already overflowed?

A good question re: how sewer water is routed to the mobile units. So far, these have been tested drawing water up from the sewer (during dry weather, actually diluting this to simulate wet weather flows), treating, then discharging back into the sewer due to permitting requirements that currently do not allow for their end-of-pipe to be its own discharge into receiving waters. So, the water they have treated with their mobile units has not overflowed and was not part of an actual overflow event, but their premise/proposition is to deploy at overflow outfall locations that may be prone to overflows. The State Street location in 2023 was located near an overflow outfall location but followed the procedure above where the tested effluent was discharged back into the MMSD system, where it made its way to Jones Island for treatment. That field experience was likely to help inform what kind of systemization/integration makes sense per your question — if say, down the road, a municipal wastewater system wanted to use this technology and deploy multiple decentralized units. We have a companion comic book that diagrams some of this to clarify what’s been done thus far versus what their aspirations are that may help illustrate this a bit more (https://refloh2o.com/water-stories). Rapid Radicals only has the two mobile units right now, both now at MMSD South Shore where testing and optimization for the tech and process integration continues. My understanding is that a lot of learning was/is happening re: the solids filtration step that is involved with drawing on actual sewer flows. As far as the particulars of siphoning, I do not know that answer; I believe there was a pump used to draw water through an intake hose. Thanks for your interest.