How 18 Municipalities Work Together on Water Quality

Their efforts clean and reduce amount of stormwater flowing into rivers and lake.

Erin Povak, watershed program manager for the Milwaukee-based nonprofit Sweet Water, tests for bacteria and chlorides on behalf of an MS4 permittee. photo courtesy Erin Povak.

As stormwater flows over urban and suburban landscapes, it picks up many contaminants — everything from pet waste to weed killers to litter. In much of our area, stormwater drains into storm sewers that carry it untreated into our rivers — a major source of water pollution.

But behind the scenes, local municipalities are improving regional water quality through green infrastructure maintenance and public education campaigns that address stormwater.

The oft-unsung actions are part of regulatory compliance with state permits for municipal stormwater, but also represent a new way of working together across boundaries.

That approach is needed because watersheds don’t observe city limits and neither do watershed-scale challenges like stormwater management.

A watershed is the area of land that drains into a water body like a river or lake. Stormwater is water that runs off the surfaces of a watershed. In the Milwaukee area, the straight-line borders of 29 municipal entities crisscross the more natural boundaries of five major river watersheds — the Milwaukee, Menomonee, Kinnickinnic, and Root Rivers and Oak Creek. Those rivers all flow to Lake Michigan.

To manage stormwater pollution, Milwaukee-area municipalities are co-signatories in “MS4” group permits — the nickname for their municipal separate storm sewer systems. MS4 discharges are permitted through the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. These permits are for stormwater only, not wastewater flushed down the toilet, which is treated separately.

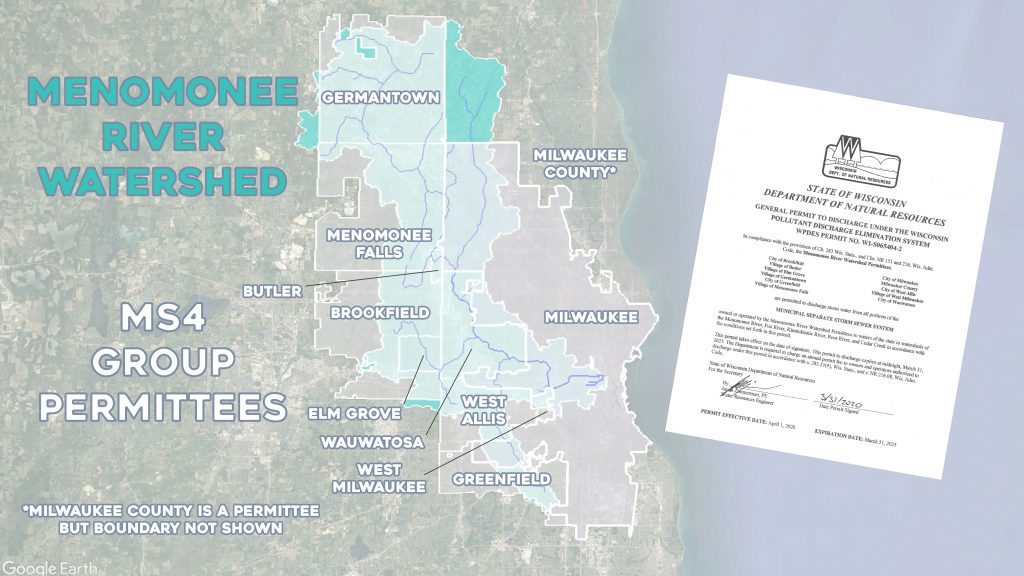

In the Milwaukee area, there are two permit groups comprising these unique intergovernmental collaborations: the Menomonee Group and the North Shore Group. The Menomonee Group has 11 co-signatories in the Menomonee River watershed. North Shore has seven in the Milwaukee River watershed.

This map overlaid on a Google Earth aerial shows the municipal boundaries of cities and villages that encompass the Menomonee River watershed. Eleven municipalities and Milwaukee County have signed a 5-year stormwater permit committing to manage water pollution together. Map illustration by Michael Timm.

The nonprofit Southeastern Wisconsin Watersheds Trust, Inc. — known as Sweet Water — works with municipal departments of public works (DPWs) to help them manage their MS4 permit compliance. Erin Povak, who joined Sweet Water in 2021, serves as the group’s watershed program director.

Povak works directly with DPWs, which are often saddled with competing tasks and limited staff time. One common thread municipalities face is maintaining green stormwater infrastructure — built features which often include vegetation to manage water where it falls, versus “gray infrastructure” which refers to pipes.

“We’re putting a lot of this green infrastructure in, but the problem is we don’t have a lot of staff to maintain it,” said Charlie Imig, director of public works for the City of Glendale, part of the North Shore Group. “Obviously, the benefits are fantastic. We want to put this stuff in. But I think it’s been a struggle.”

That’s where Sweet Water comes in, Imig said. “They have a vast volunteer group” that help with cleanup activities, for instance.

Sweet Water also helped Glendale obtain a $25,000 America in Bloom grant sponsored by CN Rail to improve landscaping at three stormwater ponds. “We’re removing invasives, removing a couple of dead trees, and then [landscaping firm] David J. Frank is going to come back through and replant some of the area,” Imig said of the 2024 project.

Under their group permits, the municipalities must also conduct targeted education and outreach on a stormwater topic of local concern. Sweet Water assists.

In West Allis, part of the Menomonee Group, water quality intersects with the local concern over pet waste.

“West Allis is pretty landlocked, so we don’t have all the tools that other areas have as far as building ponds, building large areas that can collect and treat rainwater,” said Rob Hutter, assistant city engineer for the City of West Allis. “We have to choose our methods of rainwater quality and quantity a little bit differently than other communities. So, one of the things we worked on as part of the permit — we worked on it a lot with Sweet Water — was picking up pet waste.”

This glossy postcard-sized flyer was developed by Sweet Water to help West Allis educate the public about the importance of picking up pet waste. Image courtesy Rob Hutter.

Pet waste adds bacteria to the watershed but also contributes to a rat problem. Sweet Water helped West Allis design and distribute postcards that remind the public to pick up pet waste in order to help with rat abatement. In addition, Hutter said many new apartment units in West Allis are incorporating pet waste stations to both attract tenants with pets and keep the area clean.

“We are rebranding our city,” Hutter said. “So, [our motivation is] kind of two ways. We are compelled to do it with a permit, but we also [seek a] new way we want people to look at our city.”

Hutter notes West Allis also continues to deliver subsidized $20 rain barrels to interested residents, a popular effort he said the council funds from their stormwater utility.

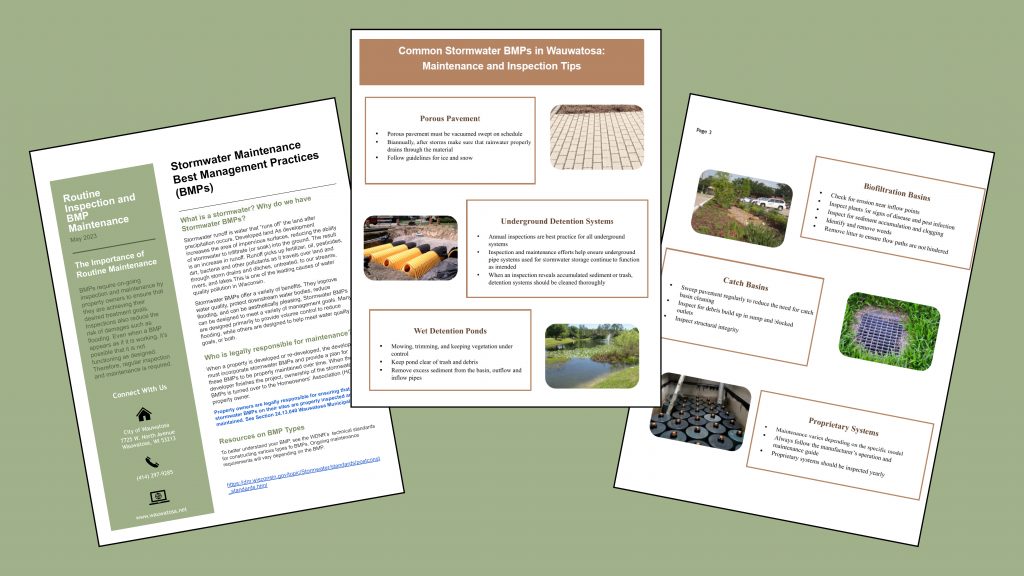

In Wauwatosa, Sweet Water helped amplify the impact of another education campaign, this one targeting owners of larger green infrastructure “best management practices” — shorthanded as BMPs. These are features like porous pavement, underground detention systems, wet detention ponds, biofiltration basins, catch basins or other proprietary systems.

Designed to minimize or manage stormwater runoff on commercial or institutional properties including schools and churches, “BMPs require ongoing inspection and maintenance by property owners to ensure that they are achieving their desired treatment goals,” according to a May 2023 letter Sweet Water helped the City of Wauwatosa send to 52 property owners listed with stormwater BMPs.

A three-page brochure Sweet Water developed to help Wauwatosa educate its property owners to inspect and maintain their stormwater BMPs. Photo courtesy Jessica Henderson.

“Inspections also reduce the risk of damages such as flooding,” the letter said. “Even when a BMP appears as if it is working, it’s possible that it is not functioning as designed. Therefore, regular inspection and maintenance is required.”

Maintenance agreements requiring annual inspection reports are binding property deed restrictions, but some may be unfamiliar with their obligations, said Jessica Henderson, civil engineer with the City of Wauwatosa. Every year Wauwatosa sends property owners a reminder letter, but the response rate was low.

“We just don’t have enough staff time generally to keep following up with property owners as it stands now,” Henderson said, so Wauwatosa worked with Sweet Water to better educate property owners sooner. After sending out an additional letter, 34 Wauwatosa properties sent their inspection records in 2023, Henderson said, up from just 15 in 2022.

Participating in the watershed-based group permits also helps municipalities learn from each other.

Sweet Water convenes quarterly meetings with the groups. “They get together and we hear presentations on various topics that are of interest,” Povak said. “The municipalities present on successes and failures.”

Hutter said West Allis is learning a lot at these meetings. “What is Greenfield doing? What is Brookfield doing? What is Wauwatosa doing? We can learn from each other, take ideas from each other or — just as importantly — ideas that didn’t work from each other are wonderful. None of this is top-secret intellectual property or anything. It’s things that we’re using public money to do, so we don’t want to repeat mistakes.”

For example, West Allis learned from Wauwatosa about porous paver best practices, he notes. West Allis initially had trouble with its porous pavers settling over the winter. Wauwatosa addressed this issue by using a fabric layer that stabilizes the pavers. West Allis changed practices to follow suit, Hutter said.

As municipalities gain more experience with maintenance, green infrastructure is growing more accepted.

Using Green Solutions dollars from the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District, West Allis installed a porous asphalt parking lot by its city hall in 2023, Hutter said. “We had a big lot and a small lot and they were separated by an alley, so we did the big lot with porous asphalt and the small lot just with regular asphalt,” he said. “It’s kind of neat to see the two on a rainy day.” The asphalt lot remains slick with rainwater while the porous surface allows water to infiltrate.

None of these activities are headline-grabbing affairs, but taken together move the needle toward cleaner Milwaukee waters we all share. Reducing pet waste reduces bacteria. Green infrastructure maintenance ratchets down other pollution metrics that communities are working together through their permits to control.

The work is also helping to change cultures within municipal government.

“I feel like one of the needles we’re pushing is with these DPW departments and the way they think about their work,” Sweet Water’s Povak said. “I’ve seen shifts happen in their perspective and thinking about stormwater from a different angle in considering the education component.”

Every five years, the MS4 group permits expire. The Menomonee Group permit was signed March 2020, so the permit will need to be revised and renewed in March 2025. The North Shore Group permit was signed June 2021 and will expire in May 2026. Renewed five-year group permits should push the needle further, Povak said.

Photo Gallery

Story by Michael Timm, a Milwaukee Water Storyteller for the nonprofit Reflo, who did our earlier series on reintroducing the sturgeon into the Milwaukee River.

This project is funded by the Wisconsin Department of Administration, Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration under the terms and conditions of Wisconsin Coastal Management Program Grant Agreement No. AD239125-024.21. Funded by the Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office for Coastal Management under the Coastal Zone Management Act, Grant # NA22NOS4190085

Great to read an article on cooperation, not confrontation.

Informative and encouraging. Thanks for this important local story.