Does ShotSpotter Reduce Crime?

Milwaukee is one of 150 cities that use it. But is there any hard evidence that it works?

Former Milwaukee Police Chief Edward Flynn was a big believer in data-driven policing and embraced ShotSpotter technology in 2010, years before many other cities, like Chicago (in 2012), New York (2015) and Houston (2022).

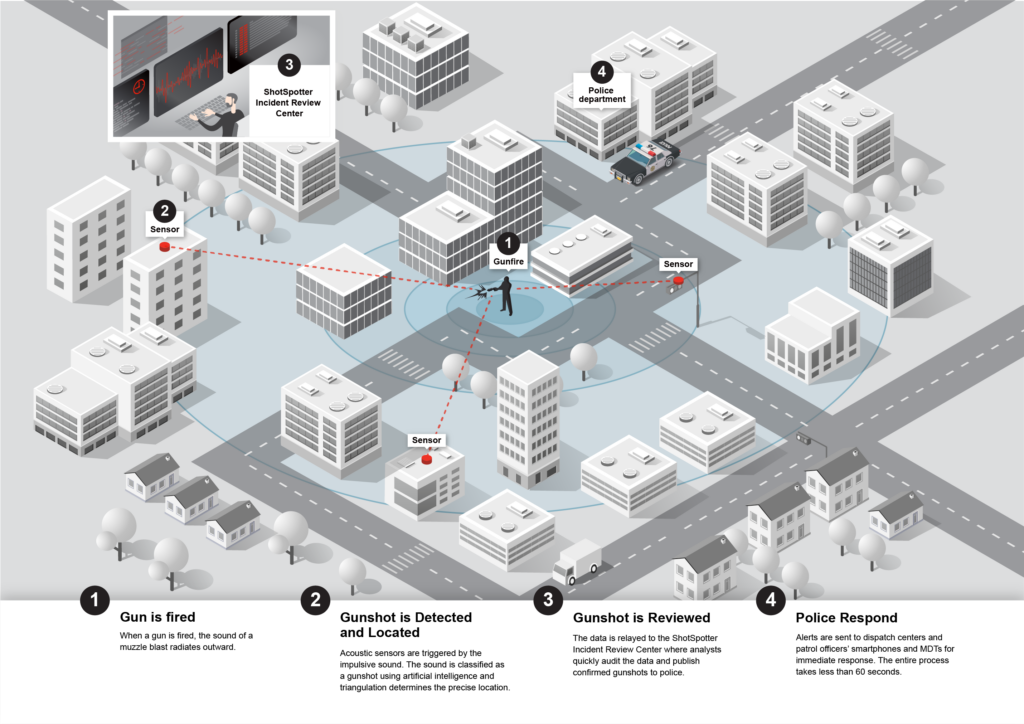

ShotSpotter was created in 1996 as a neat new way for police to track gun shots in a city. A network of acoustic sensors is installed in high-crime neighborhoods, which detects loud sounds like gunshots, fireworks, and backfiring cars. ShotSpotter’s computer system then weeds out sounds that are unlikely to be gunshots and within 60 seconds of detection, law enforcement gets a ShotSpotter alert with the time, location, and number of gun shots fired.

A 2013 story in Forbes on ShotSpotter centered on the Milwaukee Police Department (MPD) and Flynn, who was a master at getting media coverage. The story noted that ShotSpotter helped police “catch several criminals shortly after they fired shots” and “obtain convictions in several cases, including a murder conviction,” while also recovering shell casings, which were used “to provide forensic evidence in court.”

The story included some phenomenal numbers: the MPD found only 14% of the shots reported by Shot Spotter had been reported to 911. And in neighborhoods where Shot Spotter was deployed there had been a year-to-date reduction in shots fired of 18%.

You might think this would result in a decline in crimes that often involve guns, like homicide, aggravated assault and non-fatal shootings, but annual MPD reports show all three categories of crime rose after ShotSpotter was adopted, with homicides rising from 95 in 2010 to 146 in 2015, aggravated assaults rising from 3,102 to 5,202 and nonfatal shootings rising from 402 to 632 during this period.

Yet Milwaukee continued to expand ShotSpotter, as Isiah Holmes has reported for the Wisconsin Examiner. “When the system was first deployed in Milwaukee, it covered two square miles… in 2012, the system was expanded by one square mile. Then, two years after that in 2014, the system was again expanded, this time by 8.36 square miles. By the end of the second expansion, ShotSpotter was live in both the northern and southern portions of Milwaukee.”

Meanwhile many more cities had adopted ShotSpotter, which is now used by 150 cities, compared to around 20 when Milwaukee adopted it.

While MPD has never revealed which parts of the city were covered by ShotSpotter, a leak of its national data pinpointed exactly where it’s used in Milwaukee as Jeramey Jannene reported for Urban Milwaukee last week: “A southside cluster is bounded roughly by W. Greenfield Avenue, W. Lincoln Avenue, S. 6th Street and S. 27th Street. A much larger northside cluster is bounded by W. Silver Spring Drive, W. Wisconsin Avenue, Interstate 43 and N. 51st Street.”

Like Flynn, current Milwaukee Police Chief Jeffrey Norman is a fervent believer in the system. “As a department we are information-driven,” he has noted.

Yet there has never been a study in Milwaukee of the effectiveness of shot spotter, though it has now been used for 13 years. (MPD has promised a study of its “Summer Guardian” ShotSpotter program, but has yet to release any results.) Some cities have begun to raise questions about it. Chicago, Atlanta and Portland, Oregon have decided against using the system, “with city officials and others describing it as expensive, racially biased and ineffective,” CNN reported. Seattle, New Orleans; Dayton, OH; Charlotte, NC; and Trenton, NJ have also ended their ShotSpotter contracts.

A May 2021 report by the MacArthur Justice Center (MJC) reviewed ShotSpotter deployments for roughly 21 months using data obtained from the City of Chicago and found that 89% of ShotSpotter’s reports led police to find no gun-related crime and 86% turned up no crime at all, amounting to about 40,000 dead-end ShotSpotter deployments.

“I remember running the numbers and thinking, surely I’ve got something wrong here,” said MJC attorney Jonathan Manes, who worked on the research.

“The sheer number of dead-end police deployments was jaw dropping.”

An August 2021 report from the Chicago Office of Inspector General found that ShotSpotter alerts “rarely produced evidence of a gun-related crime, rarely gave rise to investigatory stops, and even less frequently lead to the recovery of gun crime-related evidence during a stop.”

In 2021, the Journal of Urban Health published a ShotSpotter study conducted by several researchers, looking at homicides and arrests for murder and weapons across 68 large metropolitan counties between 1999 and 2016, and found that implementing ShotSpotter technology had no significant impact on firearm-related homicides or arrest outcomes.

A 2022 study of a pilot program in Durham, North Carolina found ShotSpotter resulted in no reduction in gun violence, but “did notify police about more shootings compared to just 911 calls.”

And that information is exact, providing the precise longitude and latitude of where the shot was fired. That’s a great attraction for the MPD, says Ald. Scott Spiker, chair of the Milwaukee Common Council’s Public Safety Commission. “The police department greatly values it as a tool because you can locate quickly where the incident occurs,” Spiker told Urban Milwaukee.

But it also comes with no other information and can lead to countless dead-end deployments of police, the Chicago study suggested. I asked the MPD public information officer Sgt. Efrain Cornejo if police respond to every ShotSpotter report of a shot fired. “Yes, there is police response to ShotSpotter activations,” he said.

Critics have also charged that shot spotter is concentrated in Black and Hispanic neighborhoods. “You’re over-surveilling the most heavily marginalized communities in the country,” as Jon McCray Jones, policy analyst at the American Civil Liberties Union of Wisconsin, told Holmes. “It’s kind of dystopian that there are over 25,000 microphones in communities nationwide.”

But Cornejo told Urban Milwaukee that the MPD “does not use ShotSpotter to establish reasonable suspicion to stop or frisk random residents.” The technology is strongly supported by Chief Norman and Mayor Cavalier Johnson, who are both Black, and has never been opposed by Black or Hispanic members of the Common Council. “When formal resolutions for ShotSpotter grants have been before the Common Council over the past ten years, they have consistently received unanimous support,” said Jeff Fleming, spokesperson for Mayor Johnson.

Indeed, Spiker says he’s had calls from constituents asking if ShotSpotter could be installed in his far South Side district.

Holmes’ research for the Wisconsin Examiner found that Milwaukee has spent $3.7 million to date on ShotSpotter and in 2023 signed a contract to spend another $5.25 million through March 2026.

But a bigger cost concern is how this affects personnel: by far the biggest budget item for Milwaukee is for the police department, and is driven by personnel — wages and benefits and overtime for police. It’s critical that the MPD deploy its manpower as efficiently as possible

Of all the studies on ShotSpotter perhaps the most curious and disturbing finding was in St. Louis, where research found that once it was installed the number of citizen calls reporting gun shots declined. Apparently they felt they needn’t bother because ShotSpotter would report it. Once ShotSpotter was taken down, the number of citizen calls about gun shots bounced back up, increasing by 33%.

What this suggests is that ShotSpotter may disconnect police from citizens and the human dynamics of a high-crime neighborhood, while devoting all their manpower to computer reports on gun shots that lead to no crime reduction. Sometimes the fanciest technology isn’t necessarily better than old-fashioned policing.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

Political Contributions Tracker

Displaying political contributions between people mentioned in this story. Learn more.

Murphy's Law

-

National Media Discovers Mayor Johnson

Jul 16th, 2024 by Bruce Murphy

Jul 16th, 2024 by Bruce Murphy

-

Milwaukee Arts Groups in Big Trouble

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Murphy

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Murphy

-

The Plague of Rising Health Care Costs

Jul 8th, 2024 by Bruce Murphy

Jul 8th, 2024 by Bruce Murphy

What do we KNOW about the people who are pulling the trigger on the guns. Focusing on them and the trauma that they have suffered will not only decrease the number of shots fired but also the crimes associated with those crimes.