Report Gives Mixed Outlook on State’s Workers

Workers at the bottom 'did better than those at the top, reducing wage inequality.'

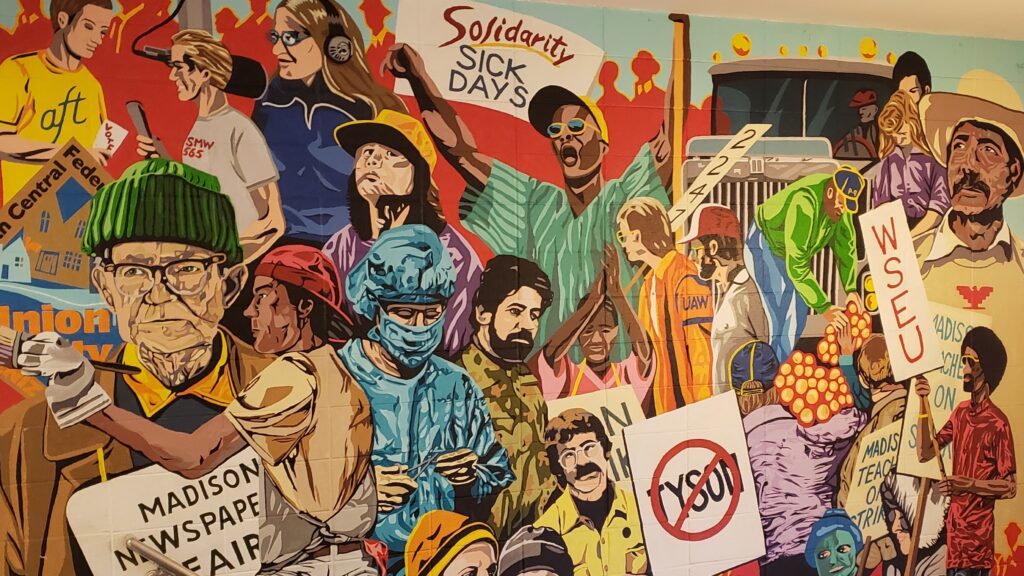

Detail of a mural inside the Madison Labor Temple building celebrating unions and worker rights. (Wisconsin Examiner photo)

Jobs are increasing and unemployment is low. Wages in 2022 didn’t quite keep up with inflation. But workers at the bottom of Wisconsin’s economy “did better than those at the top, reducing wage inequality in the state,” according to a new report published just in time for Labor Day.

The State of Working Wisconsin 2023, published by COWS, a Wisconsin research and policy analysis center, paints a mixed picture of conditions for people who work for a living in the Badger State — hopeful and challenging at the same time.

Those are the people that COWS (which was founded as the Center on Wisconsin Strategy but now just uses the acronym as its name) puts at the forefront of its analysis and research as it maps trends in wages, jobs and union membership “to build a stronger understanding of the workers’ experience of the state’s economy.”

The report is written by Laura Dresser, Joel Rogers and Pablo Aquiles-Sanchez. Rogers is COWS’ director and founder, Dresser the think tank’s associate director, and Aquiles-Sanchez its research analyst.

“Workers are seizing the opportunity provided by tight labor markets to find better jobs or improve the ones they are staying in,” Dresser said in announcing the report. “It’s especially evident that workers with lower wages have made the strongest gains. Their progress is helping reduce some of Wisconsin’s most troubling inequities.”

Highlights the report identifies in this year’s data include a record-setting Wisconsin labor market; slippage in the typically high rate of women working; increased wages that fall short of inflation, but rose the most for low-wage workers; and a surge in union interest that has been hampered by Wisconsin policies in the last decade.

More jobs, lower joblessness

The state’s monthly jobs reports hit a new record of more than 3 million in July, continuing to surpass Wisconsin’s peak number of jobs before the COVID-19 pandemic crushed employment through the summer of 2020.

In the months that followed that initial pandemic crash, Wisconsin’s job growth shot ahead of the rest of the U.S., according to the report. Since February 2022, however, it has fallen behind the country as a whole while still on a trajectory toward record job numbers this year.

“Given the different rates of recovery, the national economy recovered to the pre-pandemic jobs threshold a year before Wisconsin did,” the report states.

Leisure and hospitality workers were hardest hit by job losses early in the pandemic, with their number of jobs cut in half. They have rebounded dramatically, but still hold fewer jobs than before the pandemic.

The nature of those jobs, with “low wages, insufficient and volatile hours and few benefits” remains a challenge, the report adds, but nationally those conditions appear to be improving.

At the same time, however, the report finds “troubling trends in Wisconsin” for other job sectors. Information jobs have fallen by 8.3% since February 2020, just before the pandemic, while nationally the sector has grown 5.7%. Professional and business services jobs have grown 1.6% in that period, just a fraction of the 7.4% growth they have had nationally. Government job growth is also behind national trends.

“Taken together, weakness in these sectors — which tend to have high job quality and jobs for college graduates — presents an economic development challenge for the state,” the report warns.

More workers, but fewer of them women

A larger share of Wisconsin adults — 65.5% in July — work than in the rest of the U.S., state and federal employment data show. Unemployment rates dipped below 3%, hitting record lows of 2.4% in April and May.

“These record setting levels are consistent evidence of a strong economy and good news for workers,” the report states. Low unemployment strengthens workers’ ability to bargain for a better deal, it explains. “Workers can leverage abundant opportunities by leaving their jobs for better opportunities or using the credible threat of leaving to secure improvements in the jobs they hold.”

The COWS report zeroes in on an exception: Women, who have also worked more in Wisconsin than the nation, have been dropping out of the labor force since 2019, and last year, the share of women who are working or seeking work “dipped below 60% for the first time since the late 1980s,” the report finds.

While the report doesn’t directly explore the reason for that decline, it observes that women “carry a disproportionate burden of care for children,” making “the state legislature’s lack of investment in child care infrastructure in the state especially troubling.”

Disparities decline, but don’t disappear

On wages, the report paints a mixed picture as well.

The numbers after the dollar sign on people’s paychecks grew, but the prices on what they buy grew faster in 2022, the report observes. After accounting for inflation, the median wage was $22.02 — dipping for the first time after “a decade of wage growth.”

An exception has been for the lowest-paid workers in the state. Employers are scrambling to fill openings, and those low-wage workers “are taking advantage of the tight labor market to lift wages,” according to the report.

That has helped Black and Hispanic Wisconsin workers, whose wages have continued to rise ahead of inflation in the last four years while white workers’ wages have stagnated. “Wage inequality has declined as a result,” the report states.

With continued growth in the economy, other racial and ethnic disparities have narrowed as well, while not disappearing. The report finds that white unemployment has been a consistent 2.4% in the last year; the Black jobless rate is almost twice that, 4.7% — but it’s dropped in the same period from 5.8%.

Union approval, activism soar — but not membership

Union organizing and public support for unions are both on the increase, the report finds. A 2022 Gallup poll found that 71% of Americans approve of labor unions — a level “not seen since 1965.”

That hasn’t yet translated into more union members in Wisconsin, however.

Union membership has been declining for decades. Nevertheless throughout most of that period a larger share of Wisconsin workers have been represented by unions than in the nation as a whole.

The report says that has changed since 2012 — the year after the passage of Act 10, the Wisconsin law that stripped almost all collective bargaining rights for most public employees in the state. Since then the share of Wisconsin workers with union representation has plummeted to 8% — more than 3 percentage points below the national rate of 11.3%, and more precipitously than in any other Midwestern state.

That has hurt Wisconsin workers, the report argues.

Because Act 10 limited wage negotiations to the inflation rate, it made them virtually irrelevant, the report suggests. But it also outlawed negotiations on “some of the most important issues to workers — benefits, safety, and scheduling.” Subsequent “right-to-work” legislation weakening unions in the private sector diminished those workers’ power as well, the report states.

“When unions represent a significant share of workers in an industry, they raise job quality in that industry and even worksites outside union representation,” the report states. It credits unions for advocating policies that expand health care access, raise minimum wages and improve safety on the job, among other things.

“Inside worksites, industries, and society, unions improve pay, working conditions and policy for working people,” the report concludes “They help counteract the organized power of business interests in our society.”

Report has a mixed Labor Day outlook for Wisconsin workers was originally published by the Wisconsin Examiner.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.