Percent of Older Inmates Rising in State, National Prisons

Number of prisoners in state older than 55 tripled in 20 years, increasing medical costs.

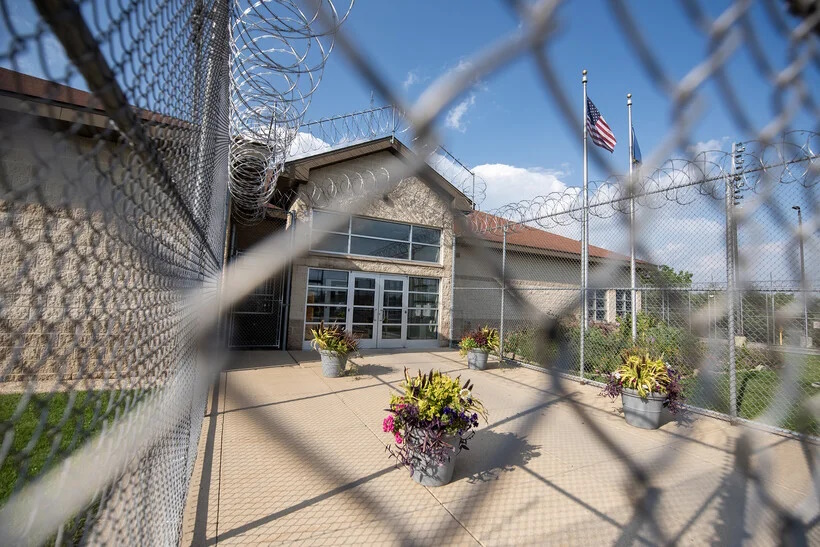

Flags, potted plants and barbed wire fencing can be seen outside Oakhill Correctional Institution on Thursday, Aug. 24, 2023, in Oregon, Wis. Angela Major/WPR

Oakhill Correctional, a minimum security facility, is surrounded by cornfields just outside Madison.

Most of the inmates there sleep in bunk beds. But, at a new unit within Oakhill, all the beds are low to the ground.

That’s so men who use wheelchairs or walkers can still access them.

“As our incarcerated population ages, we will see a greater need,” she said.

There’s more than 20,000 people locked up in Wisconsin prisons, and more than 3,000 of those people are over age 55. Over the last 20 years, that number of older prisoners has more than tripled.

On a recent summer day, Oakhill’s assisted living unit was busy with more than 20 inmates.

One man did an exercise with a nursing assistant, intended to improve range of motion in his arm. Many of the inmates there need help with showering, dressing or eating. Others have chronic conditions that require extra medical addition.

“We have many guys down there with respiratory issues, end stage COPD, emphysema, cardiac issues,” Snow said.

The graying of Wisconsin’s prison population mirrors national trends. Experts says that’s partly because the country’s population is getting older on average.

But Mike Wessler, who advocates for reducing the incarcerated population through the Prison Policy Initiative, also points to longer prison sentences.

“In the ’80s and ’90s and early 2000s, there was a real focus on kind of tough-on-crime policies that ushered in an era of mass incarceration,” he said.

In 1991, just 3 percent of men and women behind bars in state and federal prisons were 55 or older. Over the course of three decades, that percentage of older prisoners has quintupled to 15 percent.

Prison life is different for older inmates, says Harlan Richards.

Richards was 30 when he was convicted of murder after stabbing someone in a fight. He spent decades behind bars in Wisconsin before being paroled at age 67.

Increasingly, prison systems are responding to the needs of older inmates with specialized facilities. A federal prison in Massachusetts has a memory disorder unit to treat dementia. At a special needs prison in Nashville, inmates can be admitted to units with assisted living or nursing care.

In south central Wisconsin, the DOC is working to hire staff so it can increase capacity at Oakhill’s assisted needs unit to 50 prisoners. That’s in addition to a planned 15-bed facility at Oakhill for men who need rehabilitative care after surgeries or illness.

Eventually, state officials hope to open a second assisted needs unit at another Wisconsin prison. The DOC is in the early stages of exploring plans for that facility, which would be located at the medium security men’s prison in Racine.

Studies show medical costs are higher for older prisoners

Many people enter prison in worse health than the general public in part because of poverty, said Bryce Peterson, who researches policing and corrections at the CNA Center for Justice Research and Innovation.

He says medical problems can get even worse because of the conditions within prison — including violence and poor health care.

“Their physiological age is actually 10 to 15 years older than, you know, what their age actually is,” Peterson said of many people who’ve been incarcerated.

“The best estimates are that it’s anywhere from two to five times more to take care of someone who is older than it is to take care of someone who’s younger in prison,” Peterson said.

A 2015 report from the US Inspector General found federal prisons with the highest percentage of older inmates spent more than $10,000 annually per inmate on medical care. That compares to less than $2,000 per inmate at prisons with younger populations.

Those prisons with aging populations also spent much more on medications. The institutions with the most older inmates spent an average of $684 per person on meds compared to $49 at younger prisons, the report found.

At the same time, studies from Peterson and other researchers show the chance of people reoffending decreases with age.

“It’s a pretty well established phenomenon in the literature — it’s called the aging out of crime phenomenon,” Peterson said. “People tend to be less violent, less aggressive as they get older.”

Advocate says compassionate release is rarely used

Every state except for Iowa has what’s known as compassionate release policies. Those allow inmates to get out early because of advanced age or serious health problems.

But Wessler, the Prison Policy Initiative spokesperson, says compassionate release is rarely used.

“Compassionate release was never really designed for wide-scale releases,” he said. “It’s a cumbersome policy process (that) requires lots of approvals, lots of documentation.”

Of those petitions, 52 were rejected outright. An additional 13 petitions were listed as “not processed” because of circumstances including death, a petition being withdrawn or an incomplete petition packet having been submitted.

In Wisconsin, many state inmates don’t qualify for Sentence Modification Due to Extraordinary Health Condition or Age. That includes people convicted of serious felonies known as Class A or Class B offenses or anyone who committed a crime before the year 2000.

Wessler and other advocates hope for a more far-reaching solution.

“My hope is that before prisons consider opening a nursing home behind bars, states will look at revisiting some of these harsh sentencing laws,” he said.

Listen to the WPR report here.

The number of older people behind bars is skyrocketing in Wisconsin and across the country was originally published by Wisconsin Public Radio.