Program Aims To Help Inmates Avoid Opioid Addiction After Release

Behind The Walls operates from within Milwaukee's Community Reintegration Center.

David Stockton stands outside of the sober living home Wednesday, May 31, 2023, in Milwaukee, Wis. Angela Major/WPR

Five years ago, David Stockton was strung out on heroin, homeless and sleeping in a tent underneath a bridge in downtown Milwaukee.

Now, he’s one year clean and working for the homeless outreach program that helped him when he was still living on the streets.

But now, he’s on the path to recovery.

“I’m at the point in my life where I’m doing this for me, and that’s really the only way it works,” Stockton said. “You can’t do it for your loved ones. You can’t do it for probation. All of that stuff really is fleeting — you really gotta want it for yourself.”

David Stockton shows off one of the refrigerators at the sober living home Wednesday, May 31, 2023, in Milwaukee, Wis. Angela Major/WPR

At the same time, he acknowledges he’s had a lot of help. Stockton believes part of his recovery is due to a medication-assisted treatment program he started when he was still behind bars. That program, Behind the Walls, operates at the Milwaukee County Community Reintegration Center. It pairs counseling with medications that help with withdrawal and other medications that help neutralize the effects of opioids.

The outlook for people in prison dealing with addiction is grim. Overdose rates for people leaving prison are significantly higher than they are for the general public. That’s led supporters of the program to push for its expansion, as some believe it can save lives and reduce recidivism.

Last year, Behind the Walls received $2.5 million from a historic settlement of a large, multistate lawsuit against four pharmaceutical companies. The Wisconsin Department of Health Services has called the treatment the “gold standard” and pushed for its expansion at more Wisconsin Department of Corrections facilities across the state.

Now that Stockton is out of prison, he’s also pushing for the program’s expansion. For many who are struggling with addiction, he believes it’s a matter of life and death.

“People are dying, and if there’s any way we can save somebody, we need to do that,” Stockton said. “Whether it’s programming inside the jails or prisons, these things work, it’s proven that they work and it seems silly that this wasn’t happening sooner, really.”

The Milwaukee County Community Reintegration Center on Friday, June 30, 2023, in Franklin, Wis. Angela Major/WPR

Medication-assisted treatment seen as effective approach to curb overdoses

The Behind the Walls program started in 2019 after Milwaukee County received a federal grant. Before the public-private partnership began, the county would often try to get people connected to substance abuse treatment on their day of release.

“But often, that was too late,” said Jennifer Wittwer, the director of Milwaukee County’s Community Access to Recovery Services.

A 2018 study published in the American Journal of Public Health found that in the first two weeks after being released from prison, former inmates were 40 times more likely to die of an opioid overdose compared to someone in the general population. Drug overdoses are the leading cause of death after release from prison, another study found.

That’s where medication-assisted treatment comes in. The approach is seen as an effective way to treat substance use disorders and involves prescribing medication to help with withdrawal. Evidence has shown those medications help relieve withdrawal symptoms and psychological cravings from opioids.

The three U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved medications are naltrexone, buprenorphine or methadone. Methadone, the oldest and most commonly prescribed of these drugs, blocks the symptoms of opioid withdrawal and reduces or eliminates craving for opioids. Buprenorphine also blocks opioid withdrawal and reduces opioid craving. Naltrexone is what is called an “opioid antagonist.” It blocks the euphoric and sedative effects of opioids, making it difficult to use the drugs to get high.

In the Behind the Walls program, inmates are screened for a substance abuse disorder upon entering the Milwaukee County Community Reintegration Center. To qualify, an individual has to volunteer for the program and they must have a documented substance abuse disorder. Participants then begin counseling and are offered naltrexone or buprenorphine. They also get a peer support specialist, who helps the individual transition back into the community.

Intropin, (CC BY 3.0), via Wikimedia Commons

When Stockton went to prison in August of last year, he was still addicted to heroin. He got hooked on opioids shortly after he injured his back at his factory job in 2011. He decided to do physical therapy and pain management, and at the age of 33, his doctor prescribed him pain pills.

“As soon as I started taking the medication, I knew I was in trouble,” Stockton said. “The way it (opioid) made me feel, it gave me a different kind of confidence, different kind of energy. … Within weeks, I was abusing it.”

Stockton was in a pain management program for a year, which includes drug testing to ensure he’s not using any other drugs. After his third failed drug test for smoking marijuana, he was kicked out of that program.

“Once I started using heroin, that just took it to a whole new level,” he said.

Stockton was living and working in Hartford while using heroin, but he decided to move away to the Fox Valley region to get away from the problem.

“Within a week, I knew where to find drugs up there,” he said. “So that didn’t work.”

After moving to Milwaukee with a friend in 2016, he began to live in a sober living home, but was soon kicked out after testing positive for heroin.

He bounced around from homeless shelter to homeless shelter, and soon had a warrant out for his arrest after he said he cashed bogus checks to get money to pay for drugs. After arriving in prison, he learned about the Behind the Walls program.

“I knew, if I didn’t do anything, if I just sat that time, and left, I was probably going to go right back to what I was doing before,” he said. “So I decided, I’m going to do something, so that when I get released, I’ve at least got a base.”

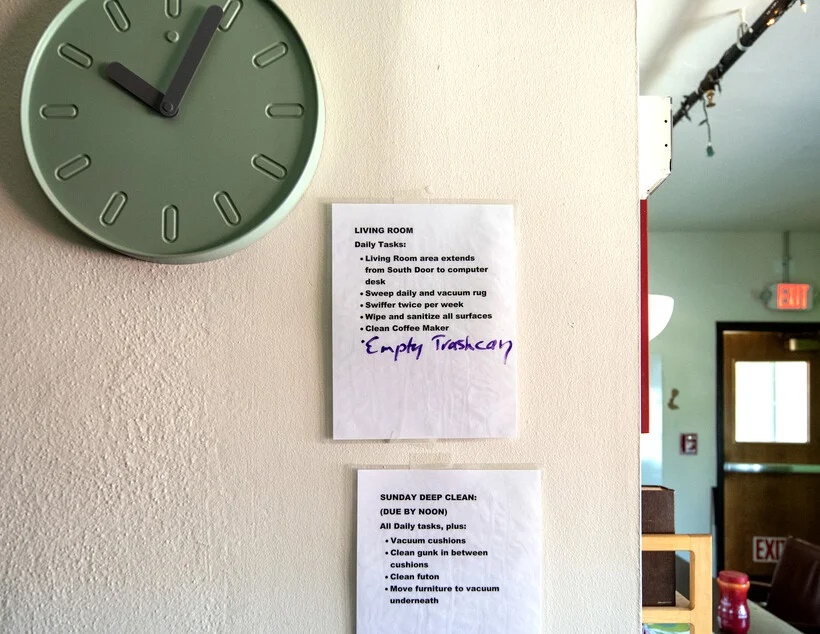

Tasks for residents to complete are listed on the wall at the sober living home Wednesday, May 31, 2023, in Milwaukee, Wis. Angela Major/WPR

Program connects individuals to treatment in community

When Stockton was released from prison, he was connected with a medication-assisted treatment facility in the community, Community Medical Services. Amy Molinski, a peer support specialist for Community Medical Services, said the goal of the program is simple.

“We want to keep our community alive. We want people to live,” Molinski said. “Being able to get somebody started in treatment while they’re already in custody, and having a plan for them … we’re relieving so much of that burden off of the individuals.”

Those in the program also get an intake appointment schedule when they leave, and often receive help with transportation and finding a place to stay when they’re released. Molinksi said she believes this reduces the burden many face when they leave prison.

“We’re offering the idea that there might be something better from what they’ve had,” she said.

Stockton said he started buprenorphine about six weeks before he was released earlier this year. He had made a plan for when he was released and had a sober living home arrangement to move into. He’s been there ever since, and is now the manager of the home.

Wittwer, the director of Milwaukee County’s Community Access to Recovery Services, said the main goal is to reduce the risk of an overdose death after individuals leave prison.

“It’s a prime opportunity when people are in what we call forced remission — they’re in a correctional facility, they can’t use — and it gives people an opportunity to really re-evaluate where they’re at in their life and what they want their life to look like post-incarceration,” Wittwer said, adding that the program will soon offer participants methadone as well.

A report from the Wisconsin Department of Health Services found that in 2020, 63 percent of people in the state’s prisons in the state had a substance use disorder. That report found that increasing services inside prisons and connecting individuals to care after release was a “best practice.”

“This layered action will reduce post-release opioid overdoses and deaths, limit illicit opioid use, and, subsequently, shrink recidivism,” the report said.

Dr. Stephanie Ruckman is the vice president of medication-assisted treatment operations at Wellpath, a private medical company that partners with the county in the Behind the Walls program. She said when people don’t have any opioids in their system for some time, they have no tolerance for them.

“We are really fighting an uphill battle with a lot of the new drugs that are continuing to be released out into society,” Ruckman said.

One of those opioids is fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine. It has spread rapidly across the nation, and the vast majority of opioid overdoses now involve the drug.

Ruckman also said if incarcerated individuals aren’t receiving substance abuse treatment while behind bars, it can create obstacles upon release.

“If they don’t have treatment or any reason to not go back to those previous behaviors, they leave the correctional facility and go right back to the behaviors they had before,” she said.

But Ruckman said she is seeing more and more states now offering the treatment for prisoners as the opioid epidemic rages on.

“This is a chronic illness that we can do something about,” Ruckman said. “This is not a failure on behalf of the person. This is something treatment exists for and we gotta offer it to people.”

Resident Chris Kelly, left, makes coffee in the kitchen of a sober living home Wednesday, May 31, 2023, in Milwaukee, Wis. Angela Major/WPR

A need to increase service

Alisha Kraus, the treatment director for the Division of Adult Institutions within the Department of Corrections, said naltrexone is offered at 15 of the 19 adult institutions across the state. Kraus said it’s not requiremed for people in treatment programs across the state to participate in mental health treatment or therapy.

“But it is encouraged,” Kraus said.

According to the DHS report, staffing for the program and funding were the main reasons it wasn’t available at more prisons. Nearly half of prison facilities in Wisconsin do not have a substance abuse counselor available to inmates.

Bonnie MacRitchie, a grants coordinator at the Wisconsin DOC, also said she believes increasing services will keep people out of custody.

“Part of our goal would be to rescue recidivism of course, so providing medications that can enable folks to continue their recovery in the community will reduce the risk of recidivism and overdose as well,” MacRitchie said.

Stockton is now a manager at Fourth Dimension, a sober living home in Milwaukee. He also works for Street Angels, a homeless outreach program in the city. On Aug. 19, he’ll celebrate his 46th birthday. One day later, he’ll celebrate one year of sobriety.

For Stockton, he believes increasing treatment options saved his life. He said counseling and the medication work “hand in hand.”

“With the proper guidance, the proper motivation, the proper medication — that brought me to a place where I found my self-worth,” he said. “And that goes a long way. That goes a long way.”

Listen to the WPR report here.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has a free, 24/7, 365-day-a-year helpline for individuals and families facing mental and/or substance use disorders. Call 800-662-HELP (4357). You can also visit their website at www.samhsa.gov.

Incarcerated people are at risk of opioid overdose after release. This Milwaukee County program aims to help. was originally published by Wisconsin Public Radio.