What’s Driving Milwaukee’s Homicide Rate

Pro-gun laws, red-lining and lead poisoning have a strong correlation with shootings.

“It makes me sad and upset as I talk about it,” says Camille Mays.

Mays is a violence prevention advocate and founder of the Peace Garden Project MKE. The last eight years have been a bittersweet tapestry of triumph and loss in Milwaukee’s struggle against gun violence. Until 2020, Mays saw first-hand how a growing violence prevention movement in Milwaukee helped curb homicides in the city. Then she lost her own 21-year-old son to gun violence, just before the numbers started to climb yet again.

Camille Mays speaks at the Red Letter Christians Revival in the Garden in Milwaukee on Saturday, Aug. 15, 2020. Photo by Erik Gunn/Wisconsin Examiner.

“I just wrapped up court for one of the murders for my son,” Mays told Wisconsin Examiner last week.

Her son, Darnell Woodard II, was shot while sitting in his car in November 2019. During the recent court proceedings, Mays says the judge commented on the mushrooming cases of violence, many of them gun-related. “It was just disheartening and heartbreaking to hear it from the judge in my case for my son,” she says.

She had been active for years working to prevent just that. “I never would have thought that — with everything that I did to fight so hard for the city to keep the gun violence down and getting so many changes done to make our city better — that it would happen,” Mays says. “I tried to do it before it hit my door, before something happened to us. I always had my son in mind.”

After years of work by Mays and other activists to reduce homicides in Milwaukee, the trend is going the wrong way.

In 2020, the Milwaukee County Medical Examiner’s office recorded 215 homicide deaths. In 2021, there were 222 homicide deaths. So far this year, according to data from the Milwaukee Police Department (MPD), 45 city residents have been victims of homicide. In mid-February, the Medical Examiner’s Office announced that homicides were already “tracking 29% higher than 2021, and 32% higher than 2020.” It’s a climb which some experts have called “the other pandemic.”

Key: Black– January | Pink– February | March- Red/Purple | April– Yellow | May – Green | June– Brown | July– Red | August– Purple | September– Light green | October– Orange | November– Violet | December– Blue *Click the square icon on the top left corner of the map to toggle between the years, and turn a year on or off.

Reggie Moore, former director of Milwaukee’s Office of Violence Prevention, underscores the need for a public health approach to homicides and other crime. While the jump in homicides since 2020 has alarmed many, he has seen other spikes in his career.

What is driving the rise? The answer involves a complex web of factors: Systemic inequity, targeted community divestment, legislative neglect, mental health needs, and environmental contamination are among them.

The last spike occurred in 2015, when the number of homicide victims jumped 69% over 2014, according to the Milwaukee Homicide Review Commission. The number of people shot in non-fatal incidents increased by 9%. Drug-related homicides rose 92% in the commission’s 2015 annual report. The number of shootings rose 13%. More than 80% of shootings in 2015 were with a handgun; just 2% involved a long gun.

Milwaukee police data classify the majority of 2015 shootings, both fatal and non-fatal, as involving arguments, robbery, or retaliation. Many others were logged as “unknown.” “Arguments” is a commonly documented cause for homicide every year, says Milwaukee County District Attorney John Chisholm. But those statistics aren’t complete. “Keep in mind we are solving homicides at a below 50% rate, and the non-fatals probably don’t break 15-20% clearance,” Chisholm cautions, “so giving a clear answer to cause is difficult.”

The 2015 surge in violence drove demand for new strategies, and it was a time of growth for the violence prevention movement. One outcome was Milwaukee’s Blueprint for Peace. The blueprint was developed with input from activists such as Mays, community stakeholders, public health experts and law enforcement. Moore credits it with producing results.

“That movement coincided with a steady four-year decline in homicides, from 2016-2019,” Moore says. But since 2020, “we’ve hit an unprecedented new reality, unfortunately, and Milwaukee’s not alone in that, in terms of these historic levels of violence.”

From January through July 2020, Milwaukee experienced a 90% increase in homicides, and a more than 65% increase in nonfatal shootings, compared with the same seven-month period in 2019.

Most often, the near-daily pattern of tragedy afflicts the most economically vulnerable and politically neglected communities in the city.

Violence, death and public health

Dr. Stephen Hargarten, a professor at the Medical College of Wisconsin and founding director of the Comprehensive Injury Center, says there may not be one clear explanation for the homicide jump in 2020.

“I think it’s a constellation of things that are bubbling up with people’s economic situation, relationship situations, interpersonal relationships,” Hargarten told Wisconsin Examiner. In 2020 the pandemic produced anxiety, workforce shutdowns and the related economic strain. Then came protests and unrest in response to the shootings of Black people by police. All of those helped set the stage for a spike in homicides, Hargarten says. And understanding homicide as a public health problem, he adds, is “critically important.”

Dr. Stephen Hargarten, a professor at the Medical College of Wisconsin and founding director of the Comprehensive Injury Center. Photo courtesy of the Medical College of Wisconsin

Once again, violence prevention strategies are getting attention. In early March, Gov. Tony Evers announced an $8.4 million grant from the state’s American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funds to Milwaukee’s Office of Violence Prevention, part of the $45 million for violence prevention and crime victim services announced in October.

Evers called the Office of Violence Prevention “a leader in taking a public health approach” to making communities, schools and streets safer. The governor also recently announced another $56 million in federal funds to address public safety, including $19 million for local police departments and $20 million for Milwaukee County criminal justice and community safety projects, with $14 million designated to expand the county’s courthouse to reduce case backlog.

In the state Legislature, however, Republicans have opted for a more punitive approach, introducing legislation to increase criminal penalties and create stricter cash bail policies. At the same time, GOP lawmakers are pushing legislation to protect gun manufacturers and distributors from lawsuits over how their guns are used.

“The state Legislature has probably been the most absent and, quite frankly, negligent in supporting communities and pursuing policies that literally could save lives,” says Moore. “Whether we’re talking about gun violence in terms of interpersonal violence, whether we’re talking about reducing domestic violence, whether we’re talking about suicides, there are policies and investments that the state can pursue that could really make a difference” — proposals to reduce the risk of accidental shootings by children, limit access to firearms and require owners to safely store their firearms.

The ARPA funds are helpful, but not permanent, he stresses. “I want people to understand that that’s a downpayment,” Moore says. “Communities across the country who are making bold investments in violence prevention are going to have to reckon with their level of commitment in sustaining that investment.”

From Walker to 2020

In 2011, then-Gov. Scott Walker signed legislation allowing Wisconsin residents to carry concealed firearms. Then in 2015, Walker signed legislation eliminating the state’s 48-hour waiting period for handgun purchases. If you’re not knowingly selling to a felon or someone else who is prohibited from owning a gun, Wisconsin presents few barriers to selling and distributing firearms.

Over Walker’s eight years in office, concealed-carry licenses in Wisconsin and homicides in Milwaukee followed a remarkably similar pattern, rising and falling almost uniformly. By itself, the pattern doesn’t show that one trend caused the other, however.

In the first year that concealed carry became legal in Wisconsin, the state Department of Justice (DOJ) approved 39,664 applications for the required license. In 2012, more than 109,000 concealed-carry licenses were approved. Nationally, gun sales set an all time record that same year.

Red line shows conceal carry licenses granted and approved by the Wisconsin Department of Justice. The blue line shows the number of new applications for conceal carry permits the DOJ received.

Homicide numbers in Milwaukee, according to data from the Milwaukee Police Department.

In 2008, the number of homicides in the city of Milwaukee fell more than 30% from the previous year to 71. In the years that followed, the number increased, but remained below 100. Then, in 2013, homicides jumped to 105, topping 100 for the first time in six years. According to the homicide commission’s 2015 report, 77% of those were due to firearms. Over the next three years, as Wisconsin’s concealed-carry license numbers dropped, so did the number of Milwaukee’s homicides.

From 2017 through 2019, state concealed-carry licenses and Milwaukee County homicides both declined. In 2019, Milwaukee’s homicides dropped to their lowest number since 2014, as did concealed carry licenses. Walker lost his re-election bid in 2018, leaving office at the start of 2019. Over the same period of time, violence prevention efforts appeared to have had an impact in the community.

The pattern has continued. As Milwaukee’s homicides jumped to 190 in 2020 and 193 in 2021, the DOJ’s concealed-carry permits increased as well.

Nationally, federal law enforcement data suggested that many guns sold during 2020 quickly made their way to crime scenes.

More data is needed to be certain

The parallel ups and downs of concealed-carry licenses and Milwaukee County homicide numbers are striking, but do they reveal anything?

“It’s interesting to look at how much that correlates,” says Hargarten. “In epidemiology, we need to have much more definitive evidence that the perpetrator has a concealed weapon carrying [permit].”

For example, there is missing data showing who sought concealed-carry licenses during peak years and where they lived. Hargarten points out that it’s unclear how many perpetrators of homicides also had a concealed weapon carrying permit. Rises could also be explained by more people wanting to protect their homes. “We don’t know that. And I think that’s where it gets to this: correlation is not necessarily related to causation,” says Hargarten.

Hargarten says researchers need data on homicide victims as well as people involved in other gun-related incidents.

“So a 21-year-old perpetrator of a gun-related homicide, did he have, or she have, a permit?” he asks. “Did a 25-year-old that died by suicide have a concealed-weapon carrying permit? Having that information routinely collected would be huge. Why isn’t that collected? Why don’t we know more about that, while we would know more about that about other pandemics that are adversely affecting our community?”

Data from the MPD is also somewhat limited. When asked how many shootings involve illegal firearms compared to those involving lawfully owned weapons, a department spokesperson said, “We do not track these categories of fatal and non-fatal shootings. They would require a manual review, which would be overly burdensome.”

Wisconsin laws reflect that, Mays says. While a person must be 21 to apply for a concealed- carry permit, an 18-year-old can legally own a handgun. “I do support gun ownership to responsible gun owners,” Mays stresses. “ I think that it’s not the guns, it’s the people who get them.”

Moore also feels that “a discourse of fear and the politics of fear and even the messaging as it related to the pandemic,” took its toll. “I think people felt that it was going to be sort of an apocalyptic reality. At the end of the day, people began to feel like they would need to defend and protect their homes and their property. And maybe people would be breaking into their houses for food and toilet paper, at the beginning of the pandemic.”

Early in the pandemic Moore observed “the drumbeat of gun violence, and that it never slowed.” He was still the director of the city’s Office of Violence Prevention at the time, and recalled having to respond to the scene of a shooting to provide support and resources. “Then literally three weeks after that was the mass shooting on 12th and Locust,” said Moore. Five people were killed ranging from 14 to 41 years old. So many people were killed, and the number of family members, friends and loved ones who showed up was so large, Moore recalled that the city passed out personal protective equipment to people on the scene to guard against the spread of COVID-19. It was Milwaukee’s second mass shooting that year; the first was at Molson Coors.

Milwaukee’s Blueprint for Peace connects the absence of gun control legislation to increased violence: “While there are no gun dealers within the city of Milwaukee, gun show loopholes and other policies related to gun ownership contribute to illegal availability and use of firearms for violence,” the document’s website states.

Over the last two years, said Moore, “you have a hell of a lot of firearms that are now present in the community that were not necessarily as present prior to 2020.” And the weapons can circulate, largely untracked. “Folks may sell these firearms, or give them away to people that may be prohibited, or sell them to people who may be prohibited from having firearms,” he added. “Which is why the gun show loophole and universal background checks are extremely important policy priorities that, again, have gone unaddressed by our state.”

Chisholm called the pandemic “a hurricane that ripped through all levels of the prevention, intervention and suppression infrastructure and exacerbated already high levels of unregulated behavior.” In addition, “no question the ubiquitous presence of firearms has contributed to the problem,” Chisholm said. “The nation, already awash with guns, bought huge quantities of guns in 2020 and ’21. Many were first-time buyers. People were afraid, and are scared.”

Nevertheless, he also cautioned against assuming that correlation equals causation. The ease with which people in Wisconsin can get a concealed weapon permit “ is just another factor to be included,” said Chisholm. “I am a firm believer that solving violent crime prevents violent crime, but when your court system has 200 homicide cases pending and 11,000 cases open, there are a lot of challenges to getting back to ‘equilibrium’ — even when equilibrium was far from perfect.”

Red-lining, lead poisoning, and signs of suffering

Data gaps aside, other things may have influenced homicide rates over the last decade. Homicides, overdoses and child deaths are all signs of suffering in a community, and Chisholm noted they typically have risen and fallen together since 2002.

Recent years have seen Milwaukee County set and break records for overdose deaths annually. During 2020, some addiction treatment centers filled to capacity with what they also described as an apocalypse effect. According the Milwaukee’s Health Department, the city’s number of infant deaths also rose from 2013-2018. For Black women, for every 1,000 live childbirths, the 15.9 babies died between 2016 and 2018, compared to 5.7 per 1,000 live births for white residents.

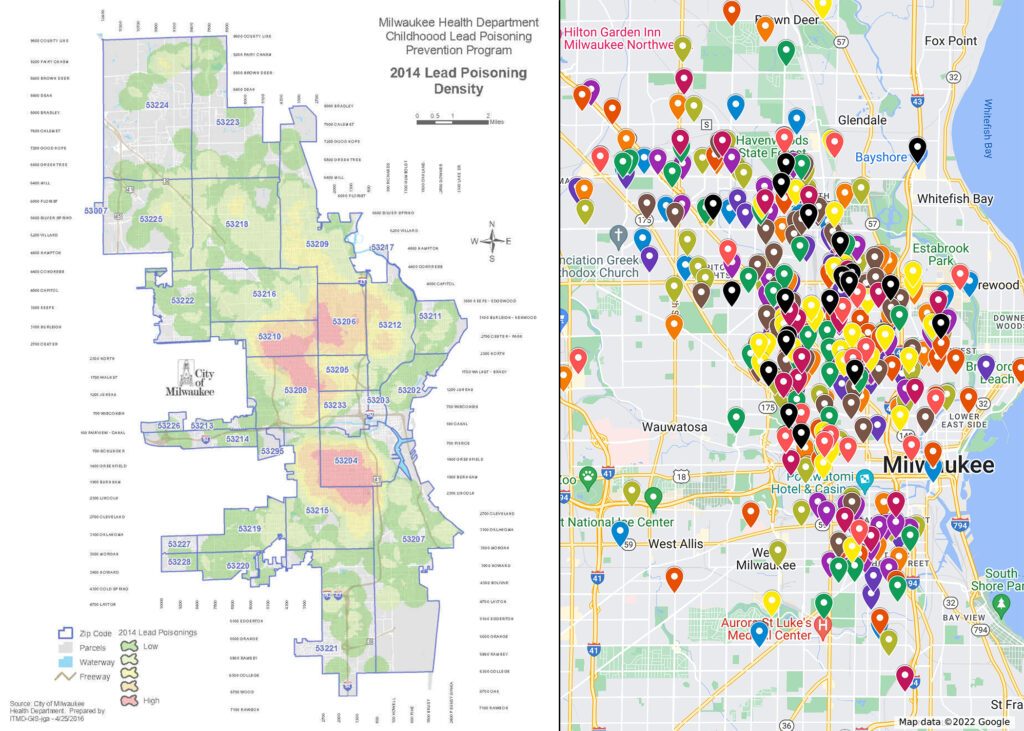

Milwaukee’s homicides also track two historic trends: Targeted community divestment over the decades due to segregation, and high rates of lead poisoning among children. On a map of homicide locations in Milwaukee County, particularly during 2020, homicides seemed to not cross an invisible line running from the northwestern part of the county, across to the southeastern corner. On the western side of that line are suburbs like Wauwatosa and West Allis.

Under red-lined segregation, investments in communities depended on whether they were considered desirable. Ideal neighborhoods were exclusively white areas, where Jim Crow-style policies could be enforced. Areas disfavored for investment were predominantly Black or Jewish. On a nearly century-old map of the red-lined districts, it’s clear that some areas marked as “definitely declining” or “hazardous” by investors decades ago are regions with high rates of homicide today. Those include Milwaukee’s Sherman Park neighborhood, as well as the South Side around the Historic Mitchell Street district.

Similarly, a 2014 map of childhood lead poisoning density in Milwaukee overlays both with the red-lining districts, and homicide density both on the north and south ends of the city. Lead poisoning is known to predispose young children to violent future behavior and lower IQ, impulsivity and antisocial behavior. Environmental hazards like lead contamination are especially prevalent in old and scarcely updated housing. Gun violence has also been linked to housing instability nationally.

The map on the left shows childhood lead poisoning density in Milwaukee during 2014. The map on the right is a the Wisconsin Examiner’s interactive map of homicides in Milwaukee County from 2020 to 2021. (Wisconsin Examiner)

In 2019, Republican leaders of the state Legislature rejected a budget proposal by Evers to provide $40 million to begin replacing more than 200,000 lead lateral service lines statewide. Milwaukee had 77,000 of those lines, and the highest rates of childhood lead poisoning. The Legislature’s Joint Finance Committee blocked the proposal; Assembly Speaker Robin Vos (R- Rochester) said of the amount of funding going to Milwaukee, “I’m not sure that that’s necessarily fair from a taxpayer standpoint.”

The same year, Vos and Assembly Republicans pushed legislation enabling landlords to speed up evictions and allowing landlords to toss out the possessions of tenants rather than paying for storage. Vos, himself a landlord with properties worth around $3.8 million, joined other legislators who voted for the bills, 1 out of 5 of whom were also landlords. Milwaukee, since 2020, has struggled with waves of evictions that clogged courts and put people out on the street.

People need hope, investment, and healing

Milwaukee’s Blueprint for Peace covers all of these issues. “Unaffordable housing and poor housing conditions negatively affect levels of violence, and the ability to establish school or community cohesion and foster stable neighborhoods,” the Blueprint states. “Poor housing conditions have historically contributed to childhood lead exposure through lead paint as well as well-researched connections between lead levels in youth and violence.” The lead connection is something that Mays and others have tried raising awareness of for some time. “A lot of us out in the community have been trying to get people to look at the homicide rates, and the lead, and some of the issues with students in schools,” said Mays.

Targeted investment in neighborhoods that desperately need it are also a cornerstone of the Blueprint. “Offering incentives to private developers and local residents to purchase residential and commercial real-estate could be catalytic to advancing neighborhood safety and resilience,” the report states. “Anchor institutions like schools, hospitals, and faith-based institutions play critical stabilizing roles for local communities.” Such investments could counteract discriminatory divestment fostered by historic red-lining.

Camille Mays also recognizes the role of economic healing — particularly in neighborhoods like the 30th street corridor, a now dead industrial sector which once offered family-supporting jobs. “With the 30th street corridor being vacated pretty much, that left the city with a tremendous loss of jobs,” said Mays. “A lot of people, you know, in the city they were employed by A.O. Smith. But a lot of those factories, it kind of left, and left the city in a rut. Kind of similar to Detroit.”

Moore finds it completely unsurprising that all of these factors seem to line up. He also stressed the importance of reducing the narrative of fear around young people in Milwaukee, a narrative that led to some being labeled “super predators” in the 1990s and is gaining new life with the recent increase in car thefts.

“People still look at young people with fear and disdain,” Moore said. And a lack of resources for teenagers and young people worsens the effect.

Grassroots organizers working within their own communities also lack support. “I feel like a lot of people don’t step into action because it doesn’t affect them directly,” said Mays. “But I know there’s people out there fighting every day. People that people don’t know about out here in the city.”

For her own place in the struggle, Mays fought for her son. “It’s very challenging staying here,” said Mays. Even after her son’s murder, Mays and others in the community continued organizing. “And then their sons have been murdered, too. Just seeing it happen over and over again is really sad.”

It’s a crisis that is misunderstood by some. Moore rejects the assumption that gang violence represents the majority of gun violence in the city. “Gun violence that we have seen, particularly over the last decade — not just in Milwaukee but around the country — is very situational, interpersonal. Whether it’s arguments, fights, road rage, disrespect,” he said — not the product of organized gang warfare.

Moore sees groups of youth in Milwaukee, and in other cities as well, organized around pain: “Some may be organized around vehicles, some may be organized around friends that they’ve lost. And they’re shooting and warring with each other not over territory, not over money, not over power, but simply just over clout and over just rage — and unmitigated pain.”

For those youth, it might be difficult to imagine a future.

“They may feel that all of their friends are dying, everybody has a gun, and the fear of, ‘I need to have this firearm,’ because they’re afraid of being shot,” Moore said. “Or they’re afraid of being caught without one. And so, those are all the dynamics that are contributing to the reality that we’re seeing, and how gun violence has evolved.”

How inequitable policies shape Milwaukee’s homicide rate was originally published by the Wisconsin Examiner.

Im not sure why leaders of milwaukee continue to pretend that they do not know how to reduce violent crime in the city. Lock up repeat violent criminals when you catch them so that they can’t harm the people of Milwaukee anymore. Stop letting career violent criminals out of jail on very low bail. I do agree that there are other root causes that need to be addressed like the underperfoming schools and break down of families as well.

Like a usual conservative this clown had completely missed the point. The problem is poverty and the white supremacist Republicans in power that use milwaukee as a scapegoat for red meat for their racist base.

Camille Mays is a wise woman and people should pay attention. I’m all for accountability – along with James Causey. But I also agree with our new police chief that “ we can’t arrest our way out o this.,.” We need both better and quicker consequences but until these young people think they have something to live and behave for the cycle continues. It’s not an either/ or – it’s a both/and…