Hmong Leaders Keeping Community Informed About COVID-19

Leaders are translating medical jargon and using existing community infrastructure.

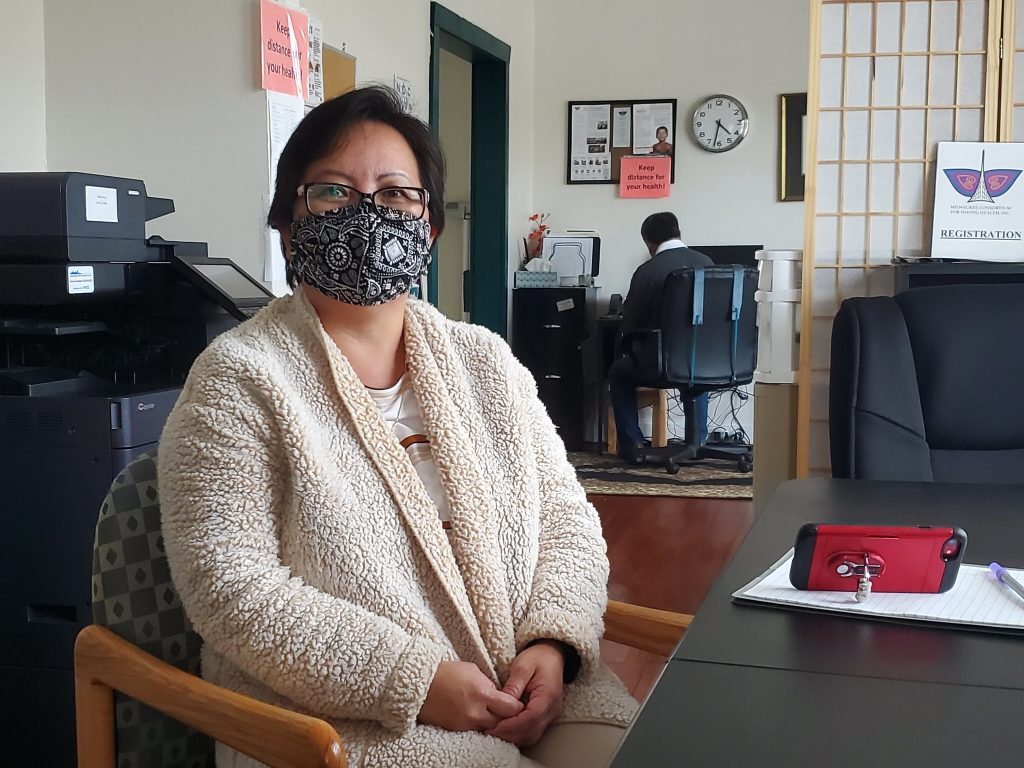

Mayhoua Moua, executive director of the Milwaukee Consortium for Hmong Health, has been trying to get the word about COVID-19 out to the community. Photo by Matt Martinez/NNS.

When Mayhoua Moua explains the coronavirus to members of her community, she often uses her own life to make her point.

A Laotian refugee who came to the United States in the mid-1970s, Moua has spent most of her life translating for her neighbors. As a young girl, she grasped English quickly. Now, she’s continuing that work by trying to inform her neighbors about the COVID-19 pandemic.

Wisconsin has the third-largest Hmong population in the United States, behind California and Minnesota. The Hmong population makes up roughly 38% of the state’s Asian population, making it the largest Asian ethnic group in Wisconsin.

There have been roughly 5,200 cases among the Asian population in Milwaukee County and 290 hospitalizations since the beginning of the pandemic. About 58% of the Asian population is fully vaccinated. Rates of cases, hospitalizations and deaths are lower in this population than compared to other racial groups.

COVID-19 vaccination data does not take specific ethnicities into account but details data on the general Asian population in Milwaukee.

Old habits, new worries

The vaccine provided temporary peace of mind, but now breakthrough cases – cases in which a fully vaccinated person gets the coronavirus — have Moua worried again.

“They think they’re OK, so now they can start gathering again,” Moua said. “Now we’re telling them, ‘No, no, no, it’s not safe.’ Even though you’re vaccinated, you need caution. And they say, ‘We thought we were supposed to be protected.’”

Lang Xiong, health advocate, job placement specialist and housing counselor with the Hmong American Friendship Association, an organization that provides resources for the Hmong community and operates a food pantry, manages a COVID-19 hotline. He said that when people call, he can offer them specific guidance on information they’re looking for, including locating vaccines and getting appointments scheduled for them.

“We’ve gotten questions like: ‘Is it something new? Is it not COVID-19 anymore? How serious is it?’” Xiong said.

In many ways, the consortium has gone back to basics. Trying to explain, for instance, that the virus can be spread by touching or talking closely to someone. Moua’s team has tried to illustrate this with videos and demonstrations through on-site workshops.

“We know how to anticipate our enemies,” Moua said. “Then with COVID, we can’t see it coming. We don’t know who may be carrying the virus. With that, our people just don’t quite understand how dangerous it can be.”

One of the biggest challenges is testing, she said. Getting all the members of a household tested for COVID after a positive exposure can be difficult, especially if they’re not feeling symptoms.

It goes hand-in-hand with her organization’s contact tracing effort, which has been trying to track the spread in the community.

“The education and the precaution and getting them to go get tested is a challenge for us right now,” Moua said. “Somebody might say, ‘Why get tested? I don’t feel the symptoms. It’s just my child.’ You interact with them, the whole family interacts with them.”

Moua was concerned about the testing rates in the community, especially as the Delta variant caused cases to increase. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC, says the variant is more than two times as contagious as other variants. Unvaccinated people are more likely to get infected and transmit the virus, the CDC says.

Chay said her work focuses on translating for a group that’s new to the country. Beyond the language barrier, transportation can be difficult. Often only one member of a family in the Karenni community can drive. As they relied heavily on carpooling and public transit, the pandemic reduced their options as bus services temporarily stopped and people were less willing to give them rides over concerns of the disease.

Trying to explain things over the phone has also made things harder, Chay said. Using a modern solution, Chay has made and shared videos on Facebook in the Karenni language. She’ll also send English versions to clients and call to confirm they understand the information.

“We don’t see each other, and we don’t interact with each other,” Chay said. “If we’re in-person, they can just come here, I translate and then do my workshop. But with COVID, I had to send them (the English version), call them and then call them again.”

Xiong said his organization employs a number of methods to get the message out. Informational flyers are passed out at its food pantry, which serves about 150 families, as people come to get meals for the week. The organization also partners with Nyob Zoo TV Milwaukee, a television news program presented in Hmong on the last Sunday of every month.

“The community is very happy to have a group that knows the culture and knows the language,” Xiong said.

Moua’s work will continue even after the pandemic ends, as she tries to raise awareness for cancer screenings and other chronic diseases in the community as well. For now, she hopes that people in the Hmong community will take the proper protection needed to combat COVID-19.

“Anything that is preventable, we need to prevent it,” Moua said. “If you know, you’re supposed to take precautions, take precautions and prevent it from happening. That’s something that our people don’t understand until they can see it–and that’s when it’s too late.”

For more information

The Milwaukee Consortium for Hmong Health is located at 1802 W. Walnut St. It can be reached at 414-212-8087.

The Hmong American Friendship Association is located at 3824 W. Vliet St. It can be reached at 414-344-6575.

More about the Coronavirus Pandemic

- Governors Tony Evers, JB Pritzker, Tim Walz, and Gretchen Whitmer Issue a Joint Statement Concerning Reports that Donald Trump Gave Russian Dictator Putin American COVID-19 Supplies - Gov. Tony Evers - Oct 11th, 2024

- MHD Release: Milwaukee Health Department Launches COVID-19 Wastewater Testing Dashboard - City of Milwaukee Health Department - Jan 23rd, 2024

- Milwaukee County Announces New Policies Related to COVID-19 Pandemic - David Crowley - May 9th, 2023

- DHS Details End of Emergency COVID-19 Response - Wisconsin Department of Health Services - Apr 26th, 2023

- Milwaukee Health Department Announces Upcoming Changes to COVID-19 Services - City of Milwaukee Health Department - Mar 17th, 2023

- Fitzgerald Applauds Passage of COVID-19 Origin Act - U.S. Rep. Scott Fitzgerald - Mar 10th, 2023

- DHS Expands Free COVID-19 Testing Program - Wisconsin Department of Health Services - Feb 10th, 2023

- MKE County: COVID-19 Hospitalizations Rising - Graham Kilmer - Jan 16th, 2023

- Not Enough Getting Bivalent Booster Shots, State Health Officials Warn - Gaby Vinick - Dec 26th, 2022

- Nearly All Wisconsinites Age 6 Months and Older Now Eligible for Updated COVID-19 Vaccine - Wisconsin Department of Health Services - Dec 15th, 2022

Read more about Coronavirus Pandemic here