Did a Janitors Union Create a Model for Rebuilding the Middle Class?

Union contract creates opportunity to expand union representation in Milwaukee County.

James Rudd speaks in favor of a bill to increase Wisconsin’s minimum wage at a Capitol press conference June 17 with Sen. Melissa Agard, right, the bill’s author. Photo by Erik Gunn/Wisconsin Examiner.

As a janitor in a downtown Milwaukee office building, James Rudd has often felt invisible.

“People think we’re just mimes — we walk through silently,” says Rudd. “No — we have skills we can use.” Skills, he says, that make the building cleaner and safer. “As a janitor, we see everything.”

And a new labor agreement for downtown Milwaukee janitors has contributed to that potential with a raise and a new venue to address working conditions with building management. It also has an opening for union janitors like Rudd to expand their ranks.

The contract between 10 building services companies and the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) spells out more clearly than before the geographic reach of the agreement. It hasn’t been tested yet, but it could grow union membership in metro Milwaukee among janitorial employees in an era when union strength has been declining for decades.

“We’re going to be backing that up with a long-term, sustained effort to win a union contract for every janitor, custodian, housekeeper, cleaner and the like in the Milwaukee regional area,” says Peter Rickman of SEIU.

Like many urban areas, union representation for janitors in Milwaukee has been largely concentrated in the legacy downtown as suburban development expands. “So being able to find a way to organize beyond the hub, beyond the old buildings that they had, is pretty crucial,” says Frank Emspak, a professor emeritus at the University of Wisconsin School for Workers.

Expanding union coverage makes it possible to “get wages out of competition,” says César Rosado Marzán, who teaches employment and contracts law at the University of Iowa College of Law. “You don’t try to compete by basically undermining your workers’ wages.”

The three-year contract took effect in August between the 10 maintenance companies and SEIU Local 1. It covers about 320 employees, which could increase to 400 as the buildings where they work return to full occupancy.

Rickman is president of another SEIU affiliate, the Milwaukee Area Service and Hospitality (MASH) Workers. MASH and Local 1, which spans six states in the upper Midwest including Wisconsin, have been collaborating in Milwaukee, with Rickman as spokesman.

Three key demands

When negotiations started in the summer, the union put down a public marker for its demands: getting janitors’ wages to $15 an hour, establishing a means for workers to voice their concerns to building managers and extending the union’s representation.

The previous agreement started workers at $11 an hour and raised that to $13.60 an hour after 12 months on the job. The new contract raised base pay to $14.15 an hour when it took effect and $15 in a year. Rickman says even that figure isn’t yet “a real living wage.” He calls it a down payment on that goal.

But federal attempts to wrest an increase foundered earlier this year, while a Democratic proposal to raise the state minimum has remained in limbo since being introduced, like most bills brought by the Legislature’s minority party. And a Wisconsin law (which the Democrats’ proposal would repeal) preempts counties or municipalities from setting local minimum wages that are higher than the state’s.

“The reality is, here in Milwaukee in 2021, we’re not going to win $15 an hour from the federal government,” says Rickman. “We’re not going to win $15 an hour from state government for sure. We’re not going to win at the city or county level given the preemption laws. The way that service sector workers in this town are raising the floor and winning $15 an hour is through union contracts.”

Early in 2020, MASH negotiated a $15 base wage for its members who work at the Fiserv Forum arena in Milwaukee, and Rickman says subsequent agreements for nursing home workers and in food service kept pace, with the janitors’ agreement the latest example.

Who is across the table

The janitors’ agreement also produced “a real long-term voice” with the union and management agreeing to an industry-wide labor-management committee to address issues such as safety and workload, Rickman says.

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, janitors were uncertain about what they were facing, says Rudd, who serves as a union steward in the building where he works. At times, “we were left in the dark, told to go clean certain areas without being told” that it had been occupied by someone infected with the coronavirus, Rudd says. “We were treated like we were kind of disposable at certain times.”

The new agreement aims to address that. “We should be in that chain of communication,” Rudd says. “We should know the seriousness of what’s going on.”

The new agreement was settled fairly quickly. “We have a pretty good working relationship with SEIU,” says Mayhall. “All of us have a common goal downtown — and that’s to provide good-paying jobs and keep buildings clean.”

In cities with an established, union-represented custodial workforce, typically concentrated in downtown office buildings, the employer side of the relationship usually has one of two forms: an association of building owners and managers, or an association of the outside companies that provide the custodial services.

Milwaukee contract negotiations follow the second approach. “We, as employers, would prefer that the SEIU negotiate with the building owners and managers, because we’re strictly the middle man,” Mayhall acknowledges. But, he adds, “That is not going to change.”

(Asked for the building owners’ perspective on the new janitors’ contract, Gabriel Fernandez, president of the Building Owners and Managers Association-Wisconsin, provided a written statement: “We recognize that it’s imperative for individuals to earn a living wage. As an association that represents owners and managers of commercial real estate, we’re currently working with our members to understand how the labor agreement will affect them and their business. There are a variety of perspectives to consider from owners, property managers, tenants and vendors, but we’re confident that we’ll find solutions that address potential challenges while satisfying workers’ needs for higher wages.”)

Expanding to the suburbs

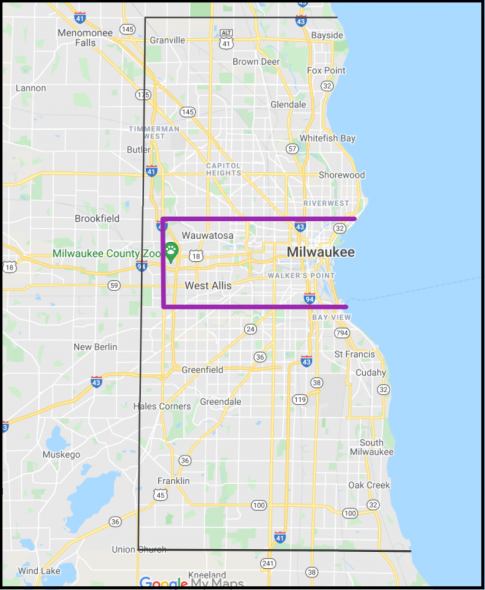

The SEIU Milwaukee janitors’ contract covers buildings inside the purple rectangle. (Wisconsin Examiner map made using My Maps from Google)

The third major provision in the new agreement added new language clearly defining the territory that the contract covers. It also creates a pathway for the union to grow in suburban Milwaukee.

The contract covers a rectangular slice of the city roughly 30 square miles, running from Lake Michigan to Interstate 41 on the city’s west side and from North Avenue south to Lincoln Avenue. If any of the 10 participating companies cleans a commercial building inside those boundaries, those custodial workers are covered by the agreement.

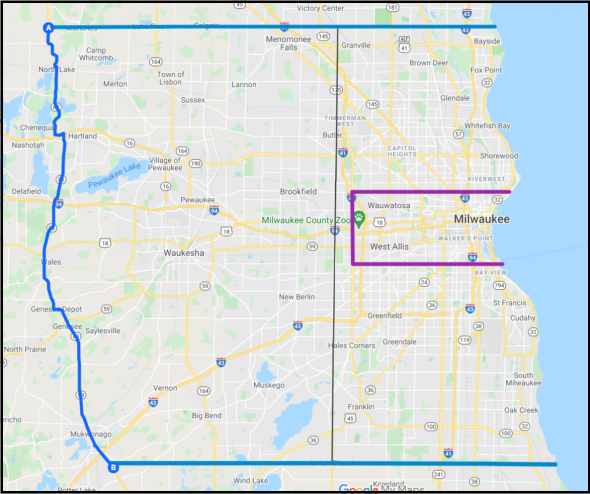

The contract also defines a broader, suburban territory that is bounded on the north and south by the Milwaukee County line and extends west to Wisconsin Highway 83, about 7 miles west of downtown Waukesha. Any local market within that region would fall under the terms of the agreement once more than half of the commercial office space in that market is cleaned by companies with a union agreement.

“This could mean additional janitorial firms signing the master contract,” says Rickman. “Or it could mean non-signatory firms agreeing to a separate union contract or neutrality agreement with the union.” Or a building owner might sign an agreement to use union contractors, he adds.

From the perspective of cleaning company employers, Mayhall says, “the decision whether the building is a union or non-union building all falls upon the building owners.”

If an owner or manager opts for a union contractor, a handful of them would bid on the work. When owners “say it’s non-union, all of us signatories don’t get the opportunity” to bid on the work, he says. For unionized employers, “within the geography you would hope that the majority of the buildings end up within the contract.”

If a building’s owner or manager plans to use a non-union cleaning service, it would then be up to SEIU to either organize those employees or persuade the building owner to choose a union contractor instead.

The new contract also provides a pathway for janitors to get union representation in the Milwaukee suburbs (bordered in blue). (Wisconsin Examiner map made using My Maps from Google)

“Building owners have a choice to make,” Rickman says. “Use responsible union contractors that ensure cleaners are paid living wages, guaranteed their rights and treated with dignity, or sweat the labor of essential frontline workers through non-union, non-responsible contractors.”

Reviving unions?

SEIU has a history of public campaigns that tie union representation to a broader social-justice agenda and of forming community alliances. Before contract talks opened, the union garnered political support from state lawmakers, Milwaukee Common Council members and most of the Milwaukee County Board.

The union has signaled that it is ready to up the ante. “Building owners across metro Milwaukee can opt for tenant disruptions and labor unrest while worsening our city’s crisis of economic and racial inequality and injustice when they go with low-road, non-union firms,” Rickman says.

In the 21st century, he maintains, Milwaukee custodial workers and other essential workers can channel the sort of strength that labor unions had a generation ago, in industries from trucking and construction to steel and autos.

“We built the world’s first middle class in this country by transforming dirty and dangerous jobs in factories and foundries into decent, family-supporting employment,” Rickman says. “When a movement of workers and politicians transformed industrial production work in the ’30s and ’40s into the bedrock of the world’s first middle class, it was public policy and union organizing that won. And you can’t tell me that the service sector can’t produce the same thing.”

The prospect of workers winning better wages and working conditions not just at a particular company but across a region also has the faint outlines of something that has seemed a distant dream for some union advocates.

In France, Germany and elsewhere in Europe, “sectoral bargaining” brings together labor unions with centrally organized employer groups, not just individual employers, says Jonah Birch, a sociologist at Marquette University. Those negotiations help set terms and conditions for entire sectors of the economy rather than isolated businesses.

Birch has researched the enactment of a 35-hour work week in France two decades ago and the subsequent bargaining to implement the new law. In Germany, sectoral bargaining between unions and industry groups starting in the metal-working industry would set wage patterns that negotiations in other sectors would subsequently follow.

“It became part of a strategy of coordinating economic activity throughout the economy,” Birch says. “It meant that unions were able to enforce wage floors — not just in one industry, but for all workers. It effectively eliminated wage differentials.”

‘People deserve a career…’

The Milwaukee agreement is a long way from those European models, to be sure. Still, Rickman would like to see something similar evolve — “an industry-wide table,” he suggests, convened by the city, with not just all the cleaning contractors but all building owners and managers taking part. “Building owners need to sit at the table and be part of the discussion about what their role and responsibility is in ensuring that these are good and decent jobs that don’t break people’s backs or spirits and provide for the health and safety protections,” Rickman says.

“It does teach you,” he says of being a union rep. “It seems fun to start with, but it is kind of a heavy thing as far as taking someone else’s problems, making them your own and representing them.”

The pending $15 hourly wage, the labor management committee and the prospect of seeing more people get the union’s coverage in the future were all important to him. But there is something else as well. The new contract has a 401(k) retirement plan. “That’s very important for my peers,” he says — some of whom have been working for 15 or even 20 years.

“There’s people out there that love this job, and they want to do this for a lifetime,” says Rudd. “People deserve a career for janitorial work. [It] isn’t just some servant cleaning up after you — they do this job professionally.”

Can a Milwaukee janitors’ contract plant the seeds of a new middle class? was originally published by the Wisconsin Examiner.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.