Anti-Panhandler Law Raises Controversy

Wauwatosa imposes fines of $25 to $500. Mayor, police department express misgivings.

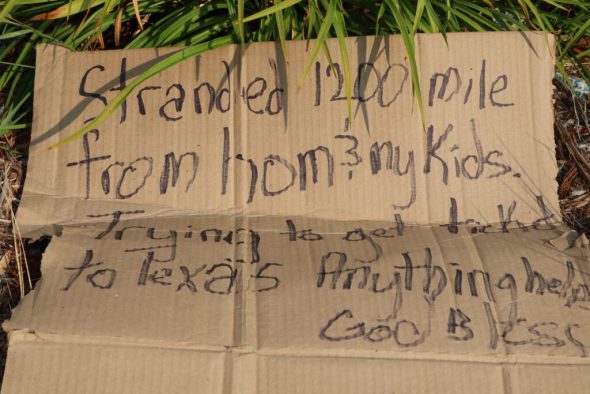

A sign lays discarded in the grass along a Mayfair Road in Wauwatosa, WI (Photo by Isiah Holmes/Wisconsin Examiner)

It’s a common experience to pass by someone standing at the median of a busy intersection holding a sign with some variation on the message “anything helps,” a handful of personal belongings lying on the ground nearby.

“We working for ourselves out here,” one man, going by the nickname Tone Tone, told Wisconsin Examiner. “That’s why people are so bothered by us.” Tone Tone was one of three men standing on Wauwatosa’s Mayfair Road intersection at North Avenue on Aug. 10. Signs in hand, enduring a humid, 90 degree day, Tone Tone and the others patiently greeted passing drivers. Wearing a bright green shirt with a smile on his face, Tone Tone noted that he tries to incorporate humor and satire into his signs. “We’re all one humanity, one people,” he said.

After an 11-3 vote on Aug. 3, the Wauwatosa Common Council passed a new ordinance to discourage that activity. The ordinance imposes fines of $25 to $500, and is framed as an effort to protect safety in the city. Some council members, like Ald. Matt Stippich, suggested that a vote be postponed until more discussion could be had with the Wauwatosa Police Department (WPD) about issues raised by the ordinance.

“This is one of those issues where we don’t like what we see on the intersection, and we’re asking the police to take care of it,” Stippich reportedly said during the council meeting, right before the vote. “As opposed to us finding a way to handle what may be a mental health issue, a poverty issue, whatever the case may be.” Since 2018, according to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, WPD has received 393 complaints from residents about panhandling, with the department receiving five to 10 calls a day.

Although Mayor Dennis McBride didn’t reply to Wisconsin Examiner’s questions about the panhandler vote, he expressed concerns around the ordinance in past weeks. “If it’s not a narrowly written ordinance, we could get accused of all kinds of things,” said McBride.

Although there has been a lot of discussion about how to deal with panhandlers, none of it has involved the people whom the new policy will directly affect.

“I’m actually mentally ill,” said Clarence, a 50-year-old Black man who posted up at the intersection of Mayfair Road and Burleigh, not far from Tone Tone and the others. Clarence, who didn’t want his last name published, told Wisconsin Examiner, “I’m bipolar, schizophrenic, [I have] depression and bad anxiety. So pretty much, I can’t take care of myself as far as paying bills right now. I used to work, but I can’t even work now.”

Clarence is all too familiar with how hard life can be on the street, having lost his big toe on one foot to the elements. “I can only stand up maybe 30 minutes at a time,” he said. Before his mental illness became too crippling and when he was more physically able, Clarence said he used to be a warehouse worker. “Pretty much, the mental illness got me where I’m at right now.” To get out of the heat, Clarence maintains a tent where he rests near the intersection.

The 50-year-old describes himself as friendly, with a propensity to stand up for other people being bullied or pushed around. While Clarence had never had any issues with law enforcement, Tone Tone said he gets mixed reactions, occasionally getting hassled by police. “Sometimes they do,” he told Wisconsin Examiner when asked how police have been enforcing the panhandler law. “It just depend on what type of mood they in that day.”

The Common Council’s decision to institute the ordinance puts the police department in a bind. Under Chief James MacGillis, WPD has expressed an interest in pursuing non-punitive strategies to address panhandling complaints from residents. “Panhandling is legal and is constitutionally protected by the courts due to the free speech right to ask for money,” said WPD spokesperson Sgt. Abby Pavlik. She added that the department “typically receives complaints regarding panhandling when the caller perceives a safety issue, such as a person stepping out into traffic lanes or if a vehicle is impeding traffic when they are handing money, food, etc, to a person in the median.”

Pavlik said that WPD “initially plans on taking an educational approach to violations of the new ordinance, advising individuals of the new restrictions. We will also use these interactions to establish a dialogue and work with the individuals to identify short and long-term needs and connect them with community-based resources.”

In a way, Wauwatosa is having a case of deja vu. Back in 2018, the American Civil Liberties Union of Wisconsin (ACLU) blasted Wauwatosa and other suburban Milwaukee communities including Shorewood and Glendale for anti-panhandler laws. “Wauwatosa changed its laws in 2018 in response to our point out that its ordinance was unconstitutional,” ACLU staff attorney Tim Muth told Wisconsin Examiner. “Asking your fellow human being for assistance in a time of need is still fundamentally protected speech. Communities should do more to address those needs and spend less time on looking for ways to punish those who have fallen on hard times.”

Although homelessness has been on the rise nationally, statistics in Milwaukee show some improvement since 2020. The annual Point In Time (PIT) count put out by the Milwaukee Continuum of Care (CoC) which covers Milwaukee County, including Wauwatosa, documented 817 people without homes in January 2021. That’s a decrease from the 970 recorded the previous year, translating to a 16% decline. Part of the reason for the sudden drop in homelessness in Milwaukee County is the response to a controversial Tent City community, which sprang up underneath a downtown freeway overpass during 2019. Following months of intense local coverage the tent community was removed and many of the camp’s residents were housed.

When the pandemic began, the Milwaukee County CoC started searching for creative solutions. The Milwaukee CoC website highlights ways it coped with a decrease in emergency shelter capacity due to COVID by creating socially distanced alternatives in local hotels and motels. Other strategies include connecting people to mental health resources — the same approach Ald. Stippich called for during Wauwatosa’s panhandler vote. The question Stippich and other local officials raise is: What is the most constructive way to deal with people who are down and out?

According to Milwaukee County’s Housing Division, historically, 99% of panhandling tickets go unpaid for obvious reasons. Eric Collins-Dyke, Milwaukee County assistant administrator of Supportive Housing and Homeless Services, expressed concern about the suburban city’s new fines.

“I’m hoping the council can show some grace and expand their lens when looking at this issue,” he said. “Housing, at its core, is a fundamental human right,” he said. “Instead of approaching this from an enforcement standpoint, I think it’s time to work together on increasing affordable housing, supporting employment opportunities, and expanding community case management services.”

Milwaukee County Supv. Shawn Rolland, who’s pressed the WPD to explore new goals and strategies under Chief MacGillis, echoed the sentiment.

“Instead of working to end homelessness, the root causes of panhandling and our neighbors’ hardship, this ordinance could create yet another system that’s rigged against people in need,” Rolland said.

“I have great respect for my colleagues on the Wauwatosa Common Council, and I agree that panhandling should be addressed, but I fear that they are about to make a mistake that converts a bad situation into an absolute nightmare. Let’s pause to think: do we want to intentionally create another flash-point between our police officers and someone down on their luck? Or should we do things differently and provide people with the resources they need to secure affordable housing, find a good-paying job and escape poverty?”

Are anti-panhandler laws worth it? was originally published by Wisconsin Examiner.