Activists, Menominee Tribe Fight Back Forty Mine

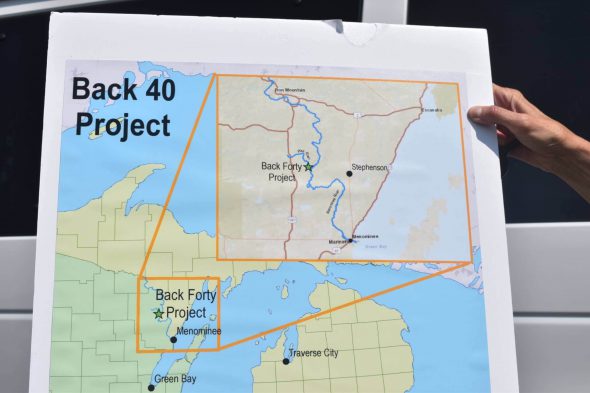

Mine to be located 50 yards from Menominee River, second largest tributary to the Great Lakes.

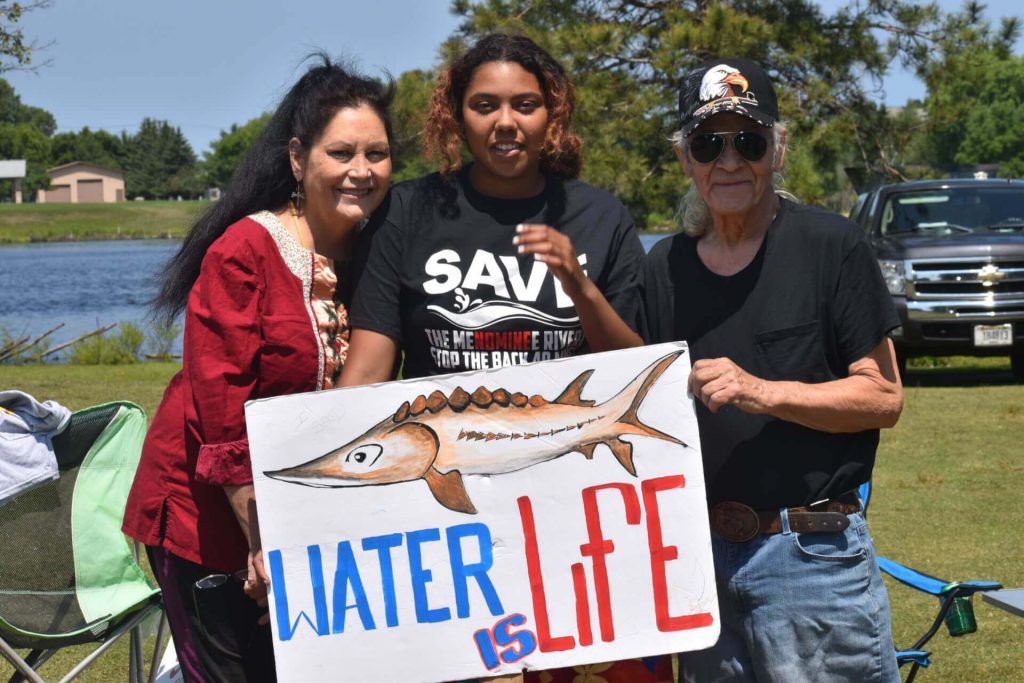

Rebecca Alegria, Aquria Sisk and Frank Alegria at water celebration on Stephenson Island, Wisc. July 16. Photo by Laina G. Stebbins/Wsiconsin Examiner.

For years, Indigenous and environmental groups have been standing up against Calgary-based Enbridge’s Line 5 oil pipeline under the Straits of Mackinac, arguing a rupture could harm the area’s freshwater and ecosystem. And about 200 miles west across Lake Michigan, in the far reaches of the Upper Peninsula, a similar story is unfolding.

On Friday, nearly 300 activists and tribal citizens gathered on small Stephenson Island in Wisconsin — a stone’s throw from the bridge separating it from Michigan — in a joint effort to protect the river that encircles it.

Dale Burie, president of Coalition to SAVE the Menominee River, speaks at water celebration on Stephenson Island, Wisc. July 16 | Laina G. Stebbins

Dale Burie established the nonprofit Coalition to SAVE the Menominee River to counter ongoing attempts by Aquila Resources to build an open-pit metallic sulfide mine near the water.

According to the Toronto-based mining and metals company, constructing the mine in Menominee County would produce significant amounts of gold, zinc, copper, silver and lead before eventually closing.

But Aquila has struggled to secure the four state permits necessary to begin the project. It also faces fierce grassroots opposition from Burie’s coalition, other environmental organizations, the Indigenous Caucus of the Western Mining Action Network and the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin itself.

“We’ve got a team of lawyers on retainer and we are prepared to fight it every step of the way,” Burie said on Friday, while hundreds gathered for the cause in Marinette.

The day featured numerous speakers, punctuated by musical interludes performed by volunteers, area musicians and tribal citizens. All speakers cited issues like water pollution, ecological disruption and air pollution that they worry could take place if the mine is built.

The permitting process for the Back Forty Mine project is currently at a standstill. After attempting several times over several years to secure all permits — and at one point securing three out of the four — an administrative judge ruled in January to revoke Aquila’s wetlands permit application for the project.

Aquila responded by withdrawing all permit applications before the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy (EGLE) in May, but vowing to come back with all new applications at the end of the year.

Diagram showing location of proposed Back Forty Mine. Photo by Laina G. Stebbins/Wisconsin Examiner.

“Aquila withdrew its permit applications in May and informed EGLE that they would resubmit new applications later in the year,” said EGLE spokesperson Scott Dean. “To date, EGLE has not seen a new mine permit application and would not expect to see an application any sooner than towards the end of this year.”

The company did not return a request for comment.

Friday’s event on Stephenson Island aimed to raise awareness and gather support for the coalition and raise money for attorney fees so the nonprofit can continue to challenge Aquila in court.

Jeff Budish, a board member of the coalition, said the group is trying to take advantage of the pause in proceedings to act and build upon its efforts.

“They’re starting, actually, from drawing [number] one again,” Budish said. “We did this to them. And the more we can keep them at bay, the longer they keep spending their money, [the better].”

The latest known iteration of the project would place the mine 50 yards from the Menominee River. In the space between, tribal burial sites and other cultural artifacts have been flagged by archaeologists and Native people.

“We have village sites, burial sites, sacred sites, traditional cultural properties, a number of things [along the river] that could be destroyed if the mine were permitted to start,” said David Grignon, a tribal historic preservation officer for the Menominee Tribe.

David Grignon speaks at water celebration on Stephenson Island, Wisc. July 16. Photo by Laina G. Stebbins/Wisconsin Examiner.

Grignon said Friday’s event was important to both rally public support and send a strong message of community opposition to Aquila.

“It shows that people of Wisconsin and Upper Michigan are very much against the Back Forty Mine,” Grignon said.

The Menominee Tribe cannot formally comment on the permit applications because it is based in Wisconsin, and the process is a state undertaking rather than a federal one.

But to the Menominee Tribe, the river is not only its cultural namesake but also their sacred place of origin thousands of years ago.

Rebecca Alegria is a tribal researcher/cultural planner for the Menominee Historic Preservation Office and a former member of the Menominee Tribal Legislature. She said the Menominee creation story is the most important story passed down to each generation of the tribe.

“When the ancestral bear emerged from the mouth of the Menominee River, it was such a force that it moved rocks and boulders and created all these new little streams and reservoirs,” Alegria said. “He was the first Menominee.”

Alegria said that the ancestral bear called down an eagle to come down from the sky and be his brother. They formed the two main clans of the Menominee: the Bear Clan and Eagle Clan. The ancestral Wolf, Moose and Crane also changed into human form and those became three more Menominee clans.

Gesturing to her 15-year-old granddaughter, Aquria Sisk, Alegria said: “We’re trying to teach the younger generation about things like this and get them interested in their identity and heritage, and so they’re able to continue this fight, because it’s probably never over.

“[Aquila] didn’t get what they wanted this time. [But] it’s not over. It’s a victory right now, but it’s never over,” Alegria said. “… This stuff never ends.”

“It’s really important to us, and for future generations that they have clean water. It’s always been an important thing to us,” Sisk added.

Natalie Lashmet, a volunteer with the coalition and a resident of Menominee Township, said mining operations are much more environmentally detrimental than they were in the gold rush era because of the small amount of ore left.

“In the olden days, mining was like mining the chocolate chips out of the cookie,” Lashmet said. “Twenty-first century mining, because the ore bodies are so poor, it’s like mining the sugar out of the cookie.”

Because the percentage of ore able to be mined is “miniscule” compared to what it used to be, “they have to not only dig up massive, massive amounts to make it cost effective for them, but they have to crush it to the consistency of talcum powder,” Lashmet said. “And all that dust with sulfide in it, when you expose sulfide to air or water, it’s going to become sulfuric acid.”

The 116-mile Menominee River is the second largest tributary to the Great Lakes and flows into Wisconsin’s Green Bay. There, the river acts as the dividing line between Menominee, Mich., and Marinette, Wisc.

The coalition has support from the Michigan Environmental Council (MEC), the Sierra Club, Canadian environmental groups and more.

Michigan Advance is part of States Newsroom, a network of news outlets that includes the Wisconsin Examiner, supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Michigan Advance maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Susan Demas for questions: info@michiganadvance.com.

Enviros and Menominee tribe fight to keep Back Forty Mine at bay was originally published by the Wisconsin Examiner.