A History of Barring Felons From Voting

It goes back to Reconstruction era. And falls heaviest on Black voters. Second story in series.

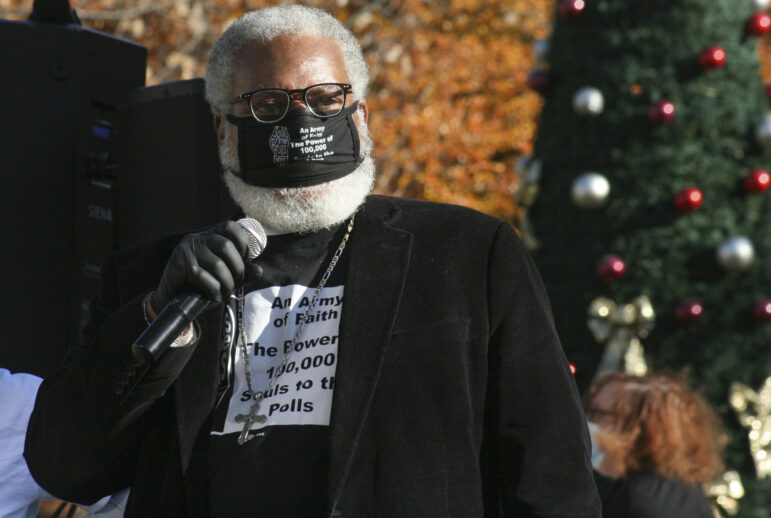

The Rev. Greg Lewis, executive director of Souls to the Polls Milwaukee, speaks during a celebration of the Joe Biden-Kamala Harris victory at Zeidler Union Square in downtown Milwaukee on Nov. 7, 2020. “When you came out and you voted and you weren’t afraid, you did what you had to do,” he said. “And now we made a difference, not only in the state, the nation, but we made a difference in the world.” Photo by Anya van Wagtendonk / Wisconsin Watch

Wisconsin’s pattern of voter disenfranchisement mirrors larger American efforts to strip voting rights from felons.

State law prohibits felons from voting while in prison and under community supervision, impacting over 68,000 Wisconsin residents. Often rooted in protecting public safety, denying voting rights to felons has been a consistent theme in the United States.

Those European countries discontinued the practice.

In fact, the European Court of Human Rights decided in 2005 that having a blanket ban on voting from prison violates the right to free and fair elections, according to Christopher Uggen, a professor of sociology and law at the University of Minnesota, and an author of a report on felony disenfranchisement.

“Indeed, almost half of European countries allow all incarcerated individuals to vote, facilitating voting within the prison or by absentee ballot,” Uggen said. “In Canada, Israel and South Africa, constitutional courts have ruled that any conviction-based restriction of voting rights is unconstitutional.”

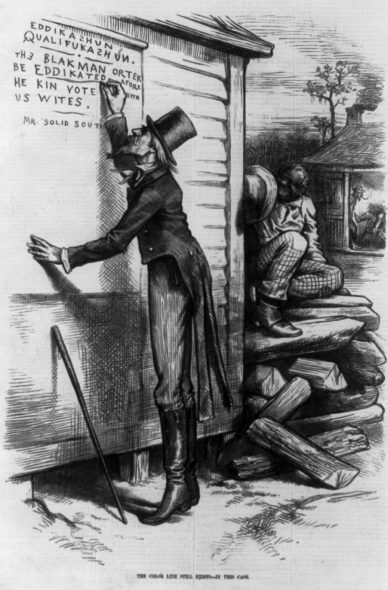

An 1879 cartoon in Harper’s Magazine satirizes the requirement that African-Americans pass a literacy test to vote. U.S. Library of Congress. (Public Domain).

How race influenced felony voter disenfranchisement

In the United States, the marriage between voter disenfranchisement and criminal history established a stronger foothold after the Civil War, when Reconstruction failed.

When Black people voted, they secured many leadership roles in the South. In response, southern states targeted Black male voters by focusing on those who committed certain crimes. In Mississippi, voters who committed burglary, theft and arson could not vote. But people convicted of robbery or murder could vote.

In his report, Uggen showed the link between crime, race and voter registration in several examples.

“The author of Alabama’s disenfranchisement provision ‘estimated the crime of wife-beating alone would disqualify 60 percent of the Negroes,’ resulting in a policy that would disenfranchise a man for beating his wife, but not for killing her. Such policies would endure for over a century,” his report stated.

A Mississippi voter registration application from 1955 outlined certain offenses that would prohibit someone from voting:

14. HAVE YOU EVER BEEN COVICTED OF ANY OF THE FOLLLOWING CRIMES: BRIBERY, THEFT, ARSON, OBTAINING MONEY OR GOODS UNDER FALSE PRETENSES, PERJURY, FORGERY, EMBEZLEMENT OF BIGAMY?

15. IF YOUR ANSWER TO QUESTION 14.IS YES, NAME THE CRIME OR CRIMES OF WHICH YOU HAVE BEN CONVICTED, AND THE DATE AND PLACE OF SUCH CONVICTIONS OR CONVICTIONS:

Uggen pointed out that it might be debatable if current disenfranchisement laws were written to reduce the political voice of communities of color, but that is the policy’s net effect.

Talking about crime became a coded way to talk about race and being racist without saying the words, said Amy Fettig, executive director with the Sentencing Project. The advocacy group promotes a fair and effective U.S. criminal justice system.

“It was no longer socially acceptable after the civil rights movement to talk about racism. White people could talk about crime without feeling like they were racist while passing laws that disproportionately impacted black and brown communities.”

Amy Fettig, executive director with the Sentencing Project

The data bears this out. One out of every nine Black people is disenfranchised compared to one out of every 50 Wisconsin voters overall; the policy impacts 68,000 Wisconsin residents. Forty-five thousand of them have been released from prison and are under community supervision, said Jerome Dillard, executive director for Ex-incarcerated People Organizing (EXPO), a Wisconsin organization that links faith communities to raise awareness about justice issues and end mass incarceration in the state.

“That’s 45,000 individuals in our community paying taxes, working and taking care of their families. But yet, they have no say on who represents them on their children’s school board, who represents the community for which the big they live and work in some, in many cases, pay taxes. Who represents them?”

Other factors playing a role in felony voter disenfranchisement

Length of community supervision and prison revocations also play a role in locking up would-be voters in Wisconsin.

The typical length of time people serve in Wisconsin under supervision is three years and two months — almost double the national average. But for some, that part of their sentence can last for decades, according to a Columbia University Justice Lab report.

“That means 10 to 15 years of paying taxes but not being able to cast the ballot, that’s 10 to 15 years of your children that been educated around voting or being able to go to the polls with you to witness that, that American process,” Dillard said.

What’s more, Wisconsin’s prison population totaled 23,755 people in 2018, and the number is expected to reach 24,350 by the end of 2021, according to the Wisconsin 2019-2021 budget. Of that, 8,774, or about 37 percent, were revoked for rule violations. This can include not showing up for appointments with a probation agent, failing to take a drug test or failing to report a new address.

Psychologically, felony voter disenfranchisement has a long-term effect on how people view themselves, and it disincentivizes people because they don’t feel like a citizen. Dillard wants to change that narrative, particularly because people of color are disproportionately impacted, he said.

“Many of us feel that we’re not a part of America,” he said. “A year after I was released, I married. My wife did well as she’s a pharmacist. So she made decent money, and we were able to purchase a home. And, you know, despite all the taxes that were paid, I was in the community for five years before I could vote.”

Voting = citizenship

Those shared experiences around race and voting left an indelible mark on Black felons experiencing voter disenfranchisement. But in some states where voting is allowed, a number of them have long waiting periods and a registration process that is difficult to navigate.

Shakur Abdullah, a restorative justice trainer/facilitator at the Nebraska Community Justice Center (CJC), said he remembers his father — a Korean War veteran — talking about trying to vote in Mississippi and being denied.

Abdullah remembers thinking that wasn’t good enough because even in prison, people remain citizens.

“Your citizenship as a direct result of your felony conviction is not abrogated. You remain a citizen,” he said.

Two years after his release, Abdullah voted for the first time. That day turned out to be an emotional experience because it triggered so many memories.

“You know, I had realized that I had just performed an act that many people that looked like me once would get killed for maybe or have to pay some poll tax to engage in. So for me, it was a really moving experience,” he said.

How voting, crime, and race became entwined was originally published by Racine County Eye.

Denied the Vote

-

Some States Restoring Felon Voting Rights

Dec 29th, 2020 by Denise Lockwood

Dec 29th, 2020 by Denise Lockwood

-

Why Most Felons in State Can’t Vote

Dec 27th, 2020 by Denise Lockwood

Dec 27th, 2020 by Denise Lockwood