QAnon Spreads to Rural Wisconsin

Its baseless theories about Democratic Satan worshippers creep into the state.

In Ferryville, a small town of less than 200 people along the Mississippi River in Crawford County, stepping out of the car brings a strong scent of fresh river water. The local gas station displays photos of former Minnesota Viking Brett Favre getting sacked by a Packer.

In October, the Crawford County village attracts plenty of passers-by enjoying the fall foliage along the National Scenic Byway.

There’s also the chance of coming across a giant symbol of a far-right conspiracy theory that’s been labeled a domestic terror threat by the FBI.

QAnon is a baseless far-right conspiracy theory that claims Donald Trump is fighting a deep state cabal of pedophiles that includes Democrats and celebrities. Henry Redman | Wisconsin Examiner

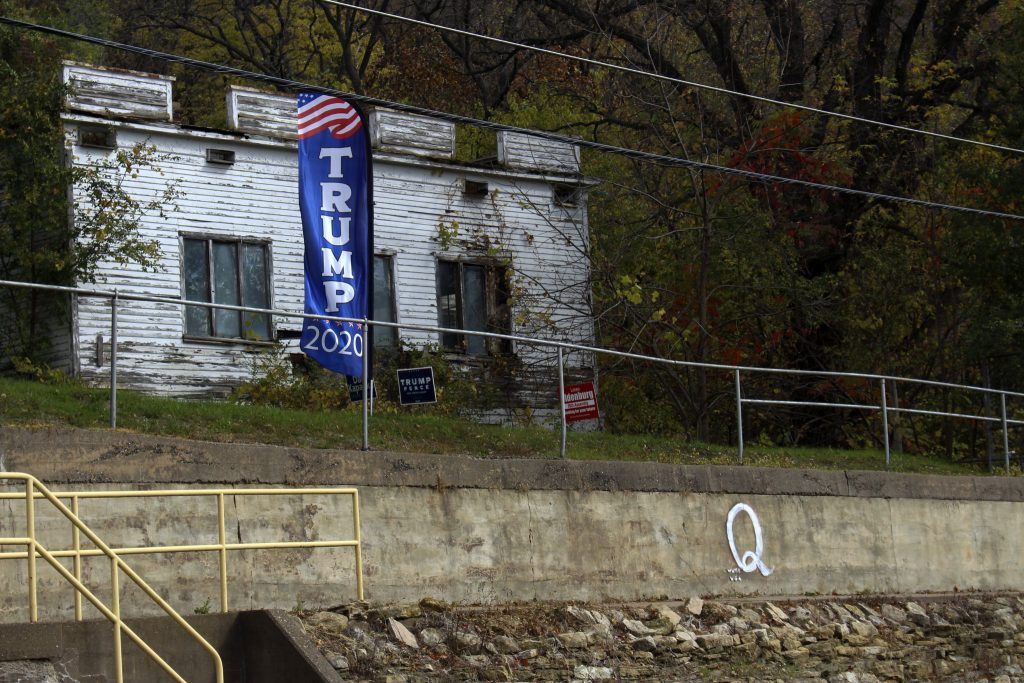

Ferryville’s Main Street doubles as part of Wisconsin’s Great River Road. On Main Street, across from a mechanic and a photography studio, is an abandoned schoolhouse with a large retaining wall in front.

On that retaining wall, in white paint are eight letters. The first letter, and the largest, is a giant “Q.” The other seven, “WWG1WGA” represent the call sign of QAnon.

QAnon is the catch-all name for a baseless set of conspiracy theories that, among other things, claim President Donald Trump is fighting a war against a deep-state cabal of Satan-worshipping, sex trafficking, pedophilic cannibals that includes Democratic politicians, the media and left-leaning celebrities.

Trump himself has winked at the conspiracy theory through retweets on Twitter and refusals to condemn the far-right movement — most recently in a televised NBC town hall last week.

Closer to home, U.S. Rep. Tom Tiffany was one of 18 members of the House of Representatives who voted “no” on a bipartisan resolution to condemn the conspiracy earlier this month. Sen. Ron Johnson appeared on Fox News on Oct. 18 to claim Hunter Biden, the son of Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden, was in possession of child pornography — a claim CNN’s Jake Tapper interpreted as a nod to QAnon’s focus on child sex crimes.

Ferryville residents have a hard time placing exactly when the graffiti went up. Many said one day they noticed some strange initials on a wall and didn’t know what they meant. The village clerk thought it was advertising a radio station.

The graffiti’s sudden appearance in Ferryville mirrors the conspiracy’s sudden appearance online a few years ago.

“[The graffiti] is a perfect analogy for how it spread online,” says Brian Friedberg, a researcher for the Technology and Social Change Project at Harvard University. “The phrases, the use of Q and WWG1WGA, were both used as really unique keywords to help spread the movement on social media and in real life.”

Anon conspiracy theorists dotted the Capitol square in April. Women have been more drawn to QAnon than other right-wing ideologies, experts say. Henry Redman | Wisconsin Examiner

The theory started on the forum 4chan in 2017 with anonymous posts about the “deep state” from someone called “Q” who claims to have high-level government security clearance. The movement quickly developed its own language and keywords. It moved to Youtube and Facebook, along with specific websites to track “drops” and other obscure forums such as 8chan that house the most radical elements of internet culture.

“The uniqueness of the keyword makes it an easy search query to fall into a data void,” Friedberg continues. “Similar things happened with a lot of other slogans in the community. These were all things that didn’t take up a lot of space on the web. The presence of those things in real life do similar services to being online.”

By 2020, the theory had multiplied, devolved and split into factions. It had gained the support of health and fitness accounts on Instagram and — notably — suburban women.

“The interesting thing about QAnon compared to other far-right ideologies is its attraction to women,” says Donald Haider-Markel, a political science professor at the University of Kansas. “Usually right-wing ideologies attract white men and older white men. It has a special appeal to women because of the focus of the conspiracies on children and threats to children. Though it’s telling that none of the real world actions we’ve seen related to QAnon so far involved women.”

In April, as people flocked to Madison from all over Wisconsin to protest Gov. Tony Evers’ stay-at-home order to prevent the spread of COVID-19, a number of rally-goers carried Q paraphernalia. COVID-related restrictions played a big role in spreading the conspiracy, experts say.

A QAnon flag displayed at April’s Reopen Wisconsin rally in Madison. Henry Redman | Wisconsin Examiner

Recently, Facebook and Youtube have moved to “de-platform” QAnon by removing accounts and groups from the networks — only now it’s too late, the conspiracy has spread, the graffiti is on the wall and no amount of banning can put the theory back into its box.

Despite how widespread the conspiracy has become, most of Ferryville’s residents fall into two categories, they’re either alarmed by the Q’s presence or have no idea what it means. One resident said he “didn’t give a sh-t about it.” Some teenagers, asked about the big Q, smiled knowingly.

Bridget Schill, the village clerk, says that once she found out what it meant she was embarrassed and that most members of the community feel the same way.

“I don’t think people are happy about it,” Schill says. “We just have to ignore it. Most people in Ferryville would like to loudly proclaim that doesn’t speak to the people of Ferryville and they’re embarrassed by it.”

Kristy Knoble recently moved to Ferryville with her 20-year-old son. She says she’s spoken about the Q with him, but not with other community members — especially as a Democrat in a largely conservative area.

In 2016, Trump won Crawford County by a slim margin. But Ferryville — with its 126 votes — voted for Hillary Clinton, 70-52 (four votes went to Libertarian candidate Gary Johnson).

This year most of the yard signs in the village are supporting Trump. Knoble, though she doesn’t think her politics match most of her neighbors, says she doesn’t think any of them are conspiratorial types.

“It’s unacceptable,” she says. “We live in a typical, small, rural, Republican community, but I’ve never had a problem with anyone here. I haven’t heard anyone else talk about [the Q].”

Kim Schmitz has lived in Ferryville for about a decade. She works across the street from the Q graffiti at the Cheapo Depot, a store advertising the sale of fireworks, tools, toys, housewares, pet supplies, greeting cards, beer, bait, tobacco, CBD, vapes and pipes.

Schmitz had never heard of QAnon, but after learning, she didn’t think the graffiti represented her town.

The property’s owner, Terrance Possehl, doesn’t live at the property but says “everybody should be able to hear the Q message.” Henry Redman | Wisconsin Examiner

“That’s kind of sh-tty,” Schmitz says. “We’re a peaceful town with friendly people.”

Schill says she’s worried about the Q because school buses drive by the property. Recently she called the property owner to see if he’d remove the paint, she says. He said he’d do it, for $50,000.

“I don’t think the village is in position for that, so now we have a Q,” Schill says. “If there were something we could do, we’d do it.”

The property owner, Terrance Possehl, lives in Fond Du Lac. He says the graffiti is there at his “consent” and he put it there “because I wanted to” — though he wouldn’t explain why he believes in QAnon or what message he was hoping to spread to Ferryville residents.

“Are you trying to put a big spin on it? What are you, a liberal?” Possehl says. “You know we don’t trust newspapers, right? I think everybody should be able to hear the Q message, right? [It’s] independent research, you don’t have to go off of what other people say.”

“They operate with certain degrees of anonymity, when someone’s willing to put those on their property, it’s a message that they’re willing to commit socially that a lot of people are only willing to commit to online,” Friedberg says. “Despite the fact that he was contacted, it doesn’t sound like he was too embarrassed by it. He’s effectively using his property as a billboard, that’s very consistent.”

Possehl says he can “do whatever he wants,” but QAnon has had dangerous real-world consequences. A man recently pleaded guilty to terrorism charges stemming from a 2018 incident in which he used an armored vehicle to barricade the Hoover Dam. In 2019, a QAnon adherent — who believed he had the protection of Trump as he attempted to fight the deep state — killed a mafia boss as he tried to perform a citizen’s arrest.

“I think it’s cause for concern amongst many folks, including in law enforcement,” Haider-Markel says. “It’s certainly true that the potential threat posed by far-right extremist groups has grown. The best thing people can do is monitor online activity about their local community and try to head off potential real world confrontations that could possibly occur. Just simply having the Q on a wall isn’t itself inherently a threat. But an idea could spread really quickly, ‘Here’s this pedophile ring operating out of this restaurant,’ that could be dangerous.”

The Crawford County Sheriff’s Office was unaware of the graffiti in Ferryville, but Lieutenant Ryan Fradette says they’ll look into it — though he acknowledged that agency leadership had to look up what QAnon was after receiving a call about it.

“This is honestly, we’re a very small rural area, this is the first we’ve heard there’s something in Ferryville,” Fradette says. “We had to even look up what it was. Around here we haven’t heard of it.”

Reprinted with permission of Wisconsin Examiner.

Nasty and dangerous propoganda should be removed from public buildings because it is nasty and dangerous.