Drugged Driving On The Rise In Wisconsin

Law Enforcement is concerned about ability to identify and prosecute drugged drivers.

“Drugged driving: One and the same,” intones a Wisconsin Department of Transportation PSA. “Driving on pills kills.”

The penalties — and devastating outcomes — are the same for drugged driving as they are for drunk driving. However convicting a drugged driver is far more complex.

Wisconsin is in most top 10 lists for the worst states for drunk driving, and while some elements that make up that ranking have improved, opioid use and marijuana legalization in surrounding states have heightened concern about a rise in drugged driving in our state.

With alcohol, a breathalyzer test provides evidence of legal intoxication. One of the best ways to secure solid evidence — to show whether the person’s driving was impaired, or not, by drugs at the time they were behind the wheel — is to have a Drug Recognition Expert (DRE)-trained law enforcement officer on the scene.

“It’s no good to put stiffer penalties in place if we are not able to prosecute the drug-impaired driver,” says Steve Krejci, the Wisconsin DRE state coordinator at the state Department of Transportation’s Bureau of Transportation Safety. “My goal has always been to get full statewide coverage with DREs in every county and region, but there are still so many underserved areas.”

But 48 out of 72 Wisconsin counties have no DREs, and many others only have one officer with DRE training. After all, explains Krejci, it saps a department’s resources to remove an officer from patrol duties to attend the intensive training. “We’re trying to overcome all these burdens for the agencies.”

Two training sessions serve up to 24 officers per session each year, and departments lose DREs to retirements or failure to keep the status active with ongoing training every two years. The course will drop to just one annual training in 2021 because a $65,000 federal grant ends this year.

“All legislators have to do is go to their county courthouses and talk to the prosecutors and ask them if they want DREs, ask if they would be beneficial,” Krejci suggests. “We want to draw attention to this issue so we get more support from these legislators.”

Full funding for experts

One legislator who gives a resounding yes to that question is Rep. Tip McGuire (D-Kenosha), who as prosecutor in Kenosha County witnessed the difference it made in the courtroom to have a DRE involved in the arrest who can then testify. “It takes 110 points of data to fully assess drugged driving,” he says. Different drugs impact the body in different ways, so DREs use a 12-step process to get those data points.

“Drug-impaired driving is a growing problem in the U.S., and the laws are complex and vary by state,” according to the Governor’s Highway Safety Association (GHSA). “There are over 400 drugs that are tracked … that can cause impairment, and each has a different impact on every user.”

For example, different drugs cause a person’s pupils to react in completely different ways. “The eyes are the windows to the soul, and for identifying intoxicants as well,” notes McGuire.

Krejci expounds on that: Eyes that are bloodshot may signal depressants but wide open eyes signal stimulants, some of which make them very white or bright. Other drugs result in watery eyes, dilated pupils, constricted pupils — all depending on how they work on the nervous system and other factors.

Among the other 110 points of information gleaned for a drug-recognition tests are hyperactivity, balance, blood pressure, body temperature, pulse, three different lighting conditions, reaction time, rebound dilation, nose and mouth checks, injection sites, muscle tone and having a conversation.

“We check their pulse a third time, then we sit down and we talk to the person,” says Krejci. “By the time we are all done, we form an opinion. Then we write up our report and that’s usually seven to eight pages long. There are 13 segments to a DRE report.”

The GHSA cites countering public attitudes on drugged driving as another major difficulty: “The public in general does not understand that marijuana and opioids can impair driving and cause crashes. In particular, many drivers who use marijuana regularly also drive after use. Similarly, many drivers who use prescription opioids feel they can drive safely after use.”

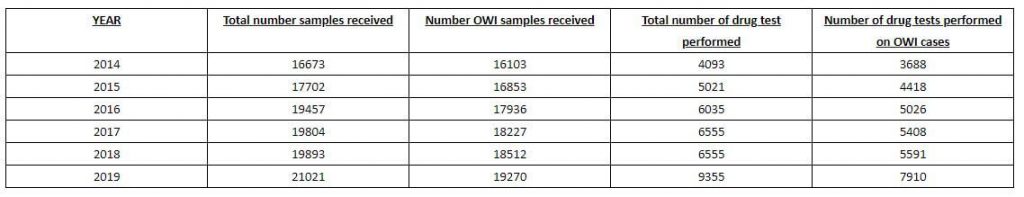

The Wisconsin State Lab of Hygiene performs drug and alcohol testing on Operating While Intoxicated (OWI) cases, as well as motor vehicle deaths and Medical Examiner death investigations, says Amy Miles, director of its Forensic Toxicology Section.

“Alcohol is always the most prevalent [substance we detect], followed by marijuana and they are often in combination,” reports Miles. “It’s typical for roughly half of the drug casework to contain marijuana. The next most common drugs over the last few years have been cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, alprazolam and fentanyl.”

While trends vacillate, Miles says these have been in the top 10 most common for the last five years. The number of drug tests (beyond alcohol) that her office performs on OWI cases has nearly doubled from 3,688 in 2014 to 7,910 in 2019.

Miles notes that drug tests are not run if the blood alcohol concentration (BAC) is above 0.1 g/100mL unless there is a Drug Recognition Expert evaluation or a crash. Tests also stop once a restricted controlled substance (cocaine, methamphetamine or delta-9-THC, LSD, PCP, hallucinogens, narcotics, etc.) is detected and that substance is reported.

Wisconsin has a zero-tolerance policy for driving under the influence of any measurable amount of a controlled substance and will treat that as an Operating While Intoxicated (OWI) offense.

“This is my opinion, but I’ve been doing this job for 23 years,” says Krejci, “and I guarantee you more people are driving on drugs other than alcohol.”

Drug recognition school

McGuire had a long conversation with Krejci in court while waiting for a jury to return, and learned about the program and what happens during an arrest to prove intoxication — which he says soon came in handy as caseloads includes more cases of driving under the influence of marijuana and prescription drugs.

“We started prosecuting more drugged driving cases and I saw what a small number of officers have this training,” says McGuire. “I thought that if we are going to loosen restrictions on marijuana at any point in the near future, we should definitely be training more people and making sure this program works.”

For several years the Legislature has focused heavily on combating drunk driving, including four bills this session authored by Rep. Jim Ott (R-Mequon), who has developed an expertise and passed bills related to drunk driving the past three sessions. Many of the bills increased penalties for multiple offenses of any type of impaired driving. But McGuire wasn’t hearing much about the complexities of drugged driving as a separate issue, even though it requires different skills at the time of arrest.

“There didn’t seem to be much conversation about it,” he says. “While the penalties are the same, the enforcement is much different. And more difficult.”

Krejci told him that the program to train DREs statewide had been expanded under a federal grant that runs out in September. Even with the grant, the program was still short of funding. So McGuire has authored a bill to fully fund DRE training with an additional $125,000 in 2020 and $250,000 in 2021, nearly doubling its $275,000 annual budget.

“That would fill the hole left by the $65,000 grant and allow us to expand substantially,” says Krejci.

Potential collaboration

Ott notes that most of his drunk-driving bills apply to both drunk driving and drugged driving — both are operating under the influence of intoxicants. “But the difficulty is that with drugs it is not an easy test like a breathalyzer. And before the whole drug issue had gotten to the point where it is now, there wasn’t much talk about them separately.”

Ott had two OWI bills signed into law by Evers already this session, and has another two that have been passed by the Assembly awaiting action in the Senate.

“Whether it’s drunk driving or drugged driving, I’m not just trying to punish people, I’m trying to get people who drive drunk to stop doing it,” says Ott.

He expresses interest in taking a look at McGuire’s bill. “Absolutely, I’m interested. Drugged and drunk driving continue to be a serious problem in Wisconsin — the job is not done,” says Ott, who has further ideas for next session as well. “And for the people who are out there enforcing the law on our roads in the middle of the night — anything we can do to make that better or easier, I think is a good idea.”

Krejci agrees: “The more arrests that are made, the more convictions that are secured, the more people are getting into the drug-treatment programs that they need — the less impaired drivers we have out on the road.”

Reprinted with permission of Wisconsin Examiner.