The Myth of Nonpartisan Judicial Elections

They could hardly be more partisan. Time to rethink how we elect Supreme Court members?

Is it time to rethink how Wisconsin chooses justices of the state Supreme Court? Wisconsin has two separate election cycles. One is for partisan offices. In August of even-numbered years, voters choose who will represent political parties in the November general election. That election combines state elections for governor and legislators with those for federal offices.

The second cycle is for positions designated as nonpartisan, including members of the state Supreme Court. These general elections occur in early April, with primaries in February to winnow the candidates for each seat down to two. Through this design the architects of Wisconsin’s election system hoped to remove certain elected officials, including judges, from partisan politics.

One result of this split is that candidates for nonpartisan offices are elected in low-turnout elections. Here are the vote totals for the most recent Wisconsin elections–the partisan election for governor in November 2018, the nonpartisan Supreme Court elections in 2018 and 2019, and the nonpartisan primary this February. These totals are for the two leading candidates for the state supreme court in the nonpartisan elections and for governor in the partisan election. Except when the spring election includes the Wisconsin presidential primary, spring turnout is less than half of that in the fall.

Low turnout presents an open invitation to wealthy special interests to drive turnout. This seems to have occurred in last year’s race between Brian Hagedorn and Lisa Neubauer. As recounted by Bill Kaplan in Urban Milwaukee and the Journal Sentinel’s Dan Bice, the Supreme Court election became a partisan election in every way except for its label.

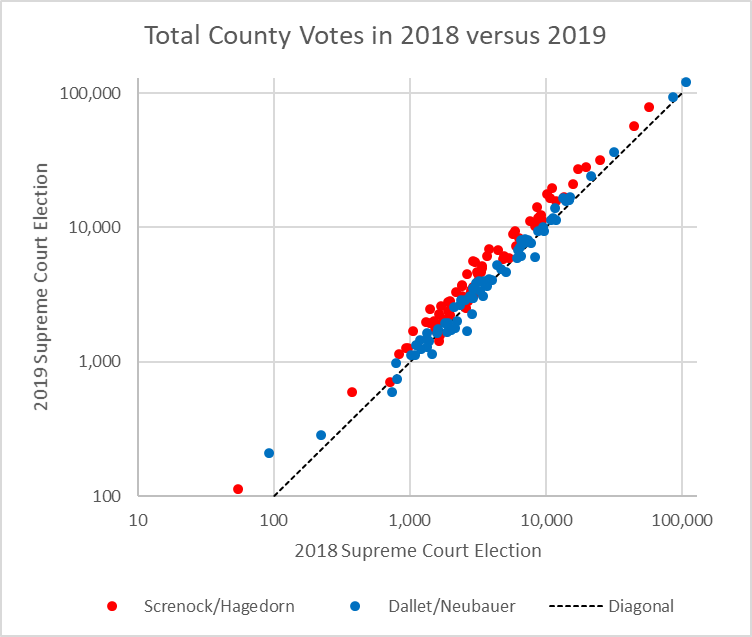

The next chart shows the resulting shift. The horizontal axis shows vote by county in 2018; the vertical axis the vote in 2019. The vote for the candidate regarded as liberal is shown in blue, the conservative candidate’s vote in red. If the votes in the two elections were the same, the dots would lie on the diagonal. Instead, both the conservative and liberal votes increased in most counties in 2019 with the conservative vote growing more.

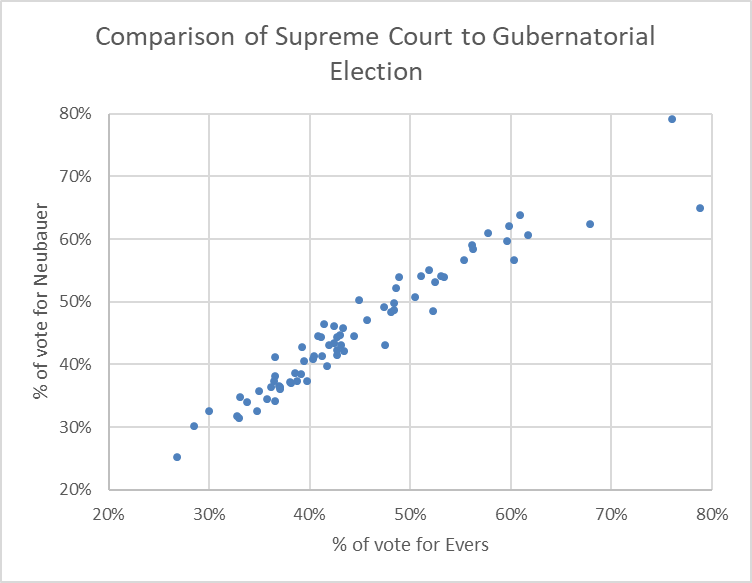

Also, partisan election results nowadays are often strongly correlated with results in nonpartisan elections. The next graph compares the percentage in each county voting for Evers in the 2018 partisan election (on the horizontal) to supporting Neubauer in the 2019 nonpartisan election (on the vertical axis).

Contrary to the hopes of the authors of Wisconsin’s Constitution, separating elections for nonpartisan offices from those for partisan offices has not prevented increasing partisanship in Wisconsin’s Supreme Court. It has, however, held down voter participation.

A recent statement from Senator Ron Johnson, distributed by the Daniel Kelly campaign, makes it clear that he and President Trump view the present Supreme Court election in partisan terms. He starts by assuring his audience that “President Donald Trump and I are in complete agreement: Wisconsin needs Justice Daniel Kelly on its Supreme Court to defend the rule of law.”

Johnson goes on to make the following points:

Justice Kelly has a conservative judicial philosophy which means he believes politics has no business on the bench. He believes judges have a solemn duty to interpret the laws as written.

We can count on him to defend the rule of law and decide cases based on the law – not the political consequences.

On April 7th, Justice Kelly will square off against a liberal activist judge who will get a big boost from liberal specialist interests who have a special interest in Wisconsin in 2020.

The liberals know that if they can win the Supreme Court election, they will seize the early momentum in this big election year. They are going all in on their liberal candidate in the hopes of undoing the conservative reforms that moved Wisconsin forward.

There are other signs that Justice Kelly is a right-wing partisan. His campaign proudly announces his endorsement by the National Rifle Association, suggesting that efforts by Milwaukee to cut down on gun violence will not receive a sympathetic audience. He also lists endorsements from Justices Rebecca Bradley and Brian Hagedorn, who together with him make up the most right-wing ideologues on the court.

The so-called Koschkee case offers insights into Kelly’s judicial philosophy. In it, then-Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Evers and the DPI were sued for not getting Governor Scott Walker’s approval before drafting a rule. The suit was brought under a 2017 law called the Regulations from the Executive in Need of Scrutiny (REINS) Act.

The first issue considered by the court was whether Evers and the DPI had a right to choose their own legal representation. Then-Attorney General Brad Schimel and his Department of Justice argued that they should represent Evers even while disagreeing with Evers’ position.

In an unsigned decision, the court majority rejected the DOJ position. It decided that Evers had the right to choose who would represent him. The court majority pointed out that the Department of Justice’s position would “not allow a constitutional officer to take a litigation position contrary to the position of the attorney general.” The DOJ’s could also create ethical issues for the state lawyers forced to represent a client while disagreeing with that client.

In June 2019, however, the court ruled against DPI, essentially giving the governor a veto over DPI rules. Asserting that “it is of no constitutional concern that the governor is given equal or greater legislative authority than the SPI in rulemaking,” the majority opinion by Patience Roggensack reversed a decision, called Coyne v. Walker, from three years earlier.

There are several reasons to be concerned about Kelly’s actions in this case.

One is his willingness—and that of Rebecca Bradley and Hagedorn–to force Evers to accept representation he did not want, and which disagreed with him. The three seemed oblivious both to the unfairness and to resulting ethical conflict this would have presented the Department of Justice lawyers.

A second reason is his cavalier dismissal of the principle of stare decisis, the idea that the court should avoid abrupt reversals of its decisions when new members join it. In dissenting from the majority’s decision, Ann Walsh Bradley (not to be confused with Rebecca Bradley) points out that “although nothing in our Constitution has changed since Coyne was decided, what has changed is the membership of the court.”

A third involves his abrupt rejection of Roggensack’s acknowledgement of the “administrative state” in paragraph 17 of her majority opinion. In it and quoting a previous decision, she says that “we have long recognized that the delegation of the power to make rules and effectively administer a given policy is necessary ingredient of an efficiently functioning government.”

This triggers 13 pages of fulminations by Rebecca Bradley against the “administrative state.” Kelly’s response is much shorter: “I join the majority opinion except with respect to ¶17.” If nothing else these fulminations firmly establish both Justice Rebecca Bradley and Kelly as full-fledged right-wing ideologues.

Fourth, he manages to effectively undercut claims by conservative jurists to just “to interpret the laws as written.” The authors of the Wisconsin Constitution used a unique model in setting responsibility for education. They could have followed the lead of some other states, for instance and given ultimate responsibility to the governor, who would have appointed a secretary of education. Instead, they decided to give responsibility to a single individual to be elected by the people.

By giving the governor veto power over education rules, Kelly and the other justices essentially thumbed their noses at the Constitution, accomplishing by decision what the authors had rejected. Making the superintendent subservient to the governor may or may not be a good idea. But either way, it should be accomplished by amending the constitution outright.

Finally, one is left wondering how much partisan considerations influenced Kelly’s votes. If Evers were governor when this suit was brought and an avid member of the Federalist Society was Superintendent of Schools, would he still vote to give the governor a veto over education rulemaking? Similarly, if in a future lame duck session, a Democratic legislative majority passes laws to clip the wings of the incoming Republic governor, would Kelly uphold the Democrats actions? We will never know for sure, but the pattern is worrisome.

Data Wonk

-

Why Absentee Ballot Drop Boxes Are Now Legal

Jul 17th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 17th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Imperial Legislature Is Shot Down

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

Counting the Lies By Trump

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

I guess this is somewhat off topic, but on this date, February 27th, in the year 1922, it was decided that “the Supreme Court of the United States held that the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution had been constitutionally established”. (The 19th amendment gave women the constitutional right to vote). The shocking thing to me is that the Supreme Court has taken this power of judicial review and it can actually go so far as to decide whether Constitutional Amendments are actually Constitutional. WTF! “Tommy Jeffs” must be spinning in his grave!!

(Thanks to the Thom Hartmann show for bringing this up today).

I have never supported the election of Supreme Court judges. The responsibilities are not “representative” in nature, such as determining public policy or allocation of government revenue. It’s not possible to eliminate political considerations from judicial selection, but accountability can actually be strengthened via an appointment process, compared to elections which are often low-turnout anyway.

Perhaps appointment by the Governor, with approval up to the State Senate, coupled with a 10-year retention election, is a reasonable alternative. I think it would be beneficial to lengthen the distance between judicial selection and an election process which, as Mr. Thompson has pointed out, is hyper-partisan.

Duane, your radio host Thom Hartmann is, at best misleading. Since 1951, the “Archivist of the United States” (part of the National Archives) certifies when an amendment is effective.

Before 1951, that task fell to the Secretary of State. In this case, Bainbridge Colby (Woodrow Wilson’s Secretary of State) certified it effective on August 26, 1920.

So what happened at the Supreme Court on February 27, 1922??

Even though the 19th Amendment was certified, some people continued to fight it all the way to the Supreme Court. The first such case to reach SCOTUS was Leser vs Garnett, in which Oscar Leser argued that the US Constitution could not override Maryland’s state Constitution (which explicitly limited voting to males).

Leser also argued that the Amendment wasn’t ratified by enough states because he claimed that some state legislatures either lacked the authority to ratify amendments or because they failed to follow their own rules.

On February 27, 1922, SCOTUS ruled against Leser, affirming that the 19th Amendment was, indeed, in effect.

TransitRider, regarding Thom Hartmann and the 19th amendment, he didn’t bring the subject up, a caller did. I’m just thankful that a show like that exists because I hadn’t a clue that the 19th amendment was challenged constitutionally, or of the mind blowing notion that someone can challenge the Constitutionality of a Constitutional Amendment after it has passed the pretty stringent hurdles of “We The People” and made its way onto the Constitution itself. If that is the case, we are not really a republic, maybe a monarchy (the monarchy being the 5 corrupt dudes in black robes, my opinion) And as far as Oscar Leser goes, I know nothing about him. But if he was able to get this challenge before the Supreme Court based on the reasons you outlined, it sounds about as ridiculous as the current challenge to the constitutionality of the ACA.