How The City Plows Snow

Inside look at how the city clears 1,475 miles of streets and 42,000 intersections.

I meet Nabor Trujillo Saturday morning at a nondescript building on the city’s southwest side. It’s one of six such sites where the city dispatches plow drivers to clear its 1,475 miles of streets.

He’s in the process of signing in alongside approximately 30 of his Department of Public Works (DPW) colleagues as the city’s two plow teams switch over. Across the city in synchronized 12-hour shifts, Trujillo and his coworkers are getting ready to head out on 103 plow-mounted salt trucks. Trujillo’s shift starts at 9 a.m., relieving the crew that has been working overnight as the snow continued to fall.

The day crew will start on the arterial streets before shifting into what DPW calls “districts.” There they will find their work supplemented by 120 plow-mounted garbage trucks, “packers” in DPW parlance, which have been out on the side streets since 4 a.m. when enough snow had fallen to ensure the heavy vehicles wouldn’t destroy the streets. A number of private contractors, many in end-loaders, work to clear sidewalks and hard-to-access spaces, while three different DPW maintenance facilities work to keep the city’s aging fleet operating as best they can.

The round-the-clock snow removal operation is usually performed in solitude, with just a driver and the vehicle’s radio. But Trujillo, who works as a DPW equipment instructor when it’s not snowing, will get some company for the first hour of his shift. I’m along for the ride to get a first-hand look at how the city tackles snow removal.

The cold-weather problem became a hot-button issue last winter as the Common Council grilled members of the department over what it said was poor performance. Aging equipment that breaks down, inexperienced drivers and staffing shortages were cited by DPW as the source of the problem.

We climb aboard, and apart from the height and control panel, the cab of the vehicle doesn’t feel much different than any other pickup truck.

Aging equipment isn’t a direct problem for Trujillo anymore. He’s driving a brand new truck this year, having been able to pick it with his seniority. It lacks that new car smell, having been driven for many other uses besides snow plowing, but is clean. Apart from less of a chance of breaking down, what’s the benefit to Trujillo? “A lot smoother ride,” says the 11-year city veteran, pointing at his seat with built-in suspension. Mine didn’t have the same suspension system and after an hour I was sold on the desirability.

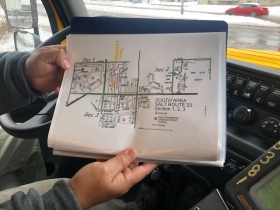

Seniority is also how plow routes are assigned. What’s desirable? Trujillo says it’s a matter of personal preference, but he prefers to stay away from the dense East Side. He’s sticking with his routes he’s had for the past few years. He brought along route maps for my benefit, but says he can do it from memory now. He’s assigned to clear the arterials or main streets from W. Lincoln St. to W. Howard Ave. between S. 27th St. and S. 43rd St. and the side streets between W. Morgan St. and W. Cold Spring St. from S. 35th to S. 68th. The latter includes a number of small cul de sacs and other irregular shapes in the otherwise grided city and some suburban areas he works around.

Before I realize what’s happening Trujillo has backed the truck up and I glance at an end loader approaching in the mirror. It’s dumping 3,000 pounds of salt into the vehicle, enough to last for his entire shift.

We pull out onto S. 35th St. and Trujillo already doesn’t like what he sees. “Whoever was on this route last didn’t plow properly,” says Trujillo. Describing conditions as “running water” where its warm enough that the salt is melting off the remaining snow, he drops the 10-foot-wide plow and begins clearing leftover snow covering the centerline. Pushing it into the travel lanes will cause other drivers to run it over, mixing it with salt and melting it. Left untouched it would become an ice ribbon dividing the travel lanes when the temperature drops later Saturday night.

Cruising over the center lane, we watch a number of drivers cautiously move over. A few come close to the plow. “I almost t-boned a lady last week,” says Trujillo of a reckless driver. He’s thankful it didn’t happen, but knows what the outcome would have been. Cars are so much smaller than the truck they won’t be winners. Collisions do occur and range from clipping a mirror to a vehicle-on-vehicle crash, Trujillo says he’s confident at least one will happen during the city’s snow removal operation. Employees that accumulate two such incidents are sent for remedial training and face potential termination. What can drivers do to make things better? “If they see us plowing, try to stay behind us,” says Trujillo as we watch a car attempt to pass.

The salt truck is also dumping salt as we’re plowing. A center console control panel allows drivers to control everything from how much is being dropped to how far it’s being thrown. Trujillo says instructions for today are 400 pounds per lane mile. He’s set it at an eight percent spread, intended to keep the salt in the travel lanes and out of the parking lanes. The trucks, even the old ones, are equipped with sensors that stop the spreading when the vehicle stops or slows the spread when it slows down (and also explains the name given to the trucks by DPW: “sensors”). Trujillo shows me a switch that during a pre-snow operation would be flipped to add brine to the mix, a strategy designed to effectively glue the salt to the roadway and increase its effectiveness.

There is one situation where the city doesn’t deploy salt – when its vehicles are in another city. Trujillo’s route take us across a short stretch of Greenfield, which he has to point out because it’s otherwise virtually invisible. The plow stays down if there is snow, as Trujillo says Greenfield would do for Milwaukee, but the salt spreader is turned off.

It’s about 10 a.m. and things look like they’re in better shape in Greenfield, while many side streets remain untouched in Milwaukee. Trujillo and other DPW employees attribute this to the suburbs being smaller. Or its a budget issue, similar to so many other things for the cash-strapped City of Milwaukee.

We turn off the arterials and head for those virtually untouched side streets.

Snow plowing on city streets is supposed to be done at speeds from seven to 15 miles per hour. A DPW instructor, one of 11, says he teaches employees during their two-day courses to put the automatic-transmission truck in second gear to regulate their speed if need be and allow for maximum precision. “I could throw snow on that person’s porch,” says Trujillo as we roll by a number of homes. I resist the urge to make ask him to prove it.

Plenty of residents are out shoveling, a few of which stop to wave. Trujillo says every so often he gets one making the “you’re number one” sign with their middle finger. “I had a shovel thrown at my truck once,” he says.

Residents frustration with plowing can come from blocked driveways or plowed-in vehicles after the plow does its work. “Our biggest problem is a lot of people don’t move their cars,” says Trujillo. The city issues thousands of tickets during snow storms (3,850 on Saturday alone), particularly when it declares an overnight snow emergency requiring alternate side parking. Trujillo says the leftover vehicles block access to the curb, even those parked legally, and cause a cascade of issues. This is compounded with inexperienced drivers says Trujillo.

“We have a lot of new employees. They’re nervous,” says Trujillo. It’s easy to see why. Trujillo seems to effortlessly steer the truck, adjusting the angle on the plow to push the snow forward when we’re next to vehicles instead of into them and walking me through what he’s doing. I’m struggling to just keep track of where we are after we make countless turns and end up doubling back to plow the opposite of the street we just went down. “They’re trying,” says the veteran of the new employees. Over 50 of the plow drivers are new this year and over half of the force has less than five years of experience.

Trujillo’s familiarity with the route is obvious. He points out cars that will be there during the entire snowstorm and others he expects to move. He also notes certain homeowners that do a good job clearing their property (the city advises people clearing driveways to push the snow to the far side so it doesn’t get plowed back in front of it). He intends to make three passes through his entire route during his shift.

“I gotta talk to this guy,” says Trujillo as he suddenly stops the truck. He heads over to talk to a private operator who is clearing the snow from a funeral home parking lot by pushing it into the street. “That’s illegal,” he says, and more problematic because it was being pushed into a frontage road, Trujillo wouldn’t have anywhere to push it outside of into the main road. He says the operator said he didn’t know the rules and promised to stop.

Things today are going relatively smoothly, says Trujillo, at least compared to having to work in rush hour. He says the traffic volume slows things down and makes the job more difficult.

As a passenger, it’s easy to forget that the truck is plowing snow. You can’t see it because of how high you sit above the plow and the vehicle has so much power you can barely feel it. To see what we’ve done I need to look in the side mirror. Orange plastic posts are mounted on the edge of the plow so Trujillo knows where it is, but, with a laugh, he notes that he’s short and has had a second one added to the far side.

But when Trujillo goes for the curb there is no mistaking where it is. You hit it with a thud, even at slow speeds. It’s not surprising that new drivers don’t always get all the way to it, especially given the number of parked cars we have to steer around.

We pass a parked “packer” parked outside a Cousins Subs. Trujillo notes they’re probably on their lunch break, having been out plowing since before the sun rose. The city can monitor the location of every vehicle from its sixth-floor operations center at the Zeidler Municipal Building next to City Hall. Trujillo says he’ll break for a half-hour lunch and take another 15-minute break.

What would our experience be like if Trujillo had taken me out in a garbage truck instead of the “sensor” we’re riding in? “A lot bumpier,” he says without hesitation. The plow is also up to two feet wider, which adds complexity, and power, to the job.

Having shown me the ropes, we head back to the garage. Trujillo has another 11 hours of plowing ahead of him. Then he’ll be back in at 9 a.m. on Sunday where he expects to be working some of the smaller equipment the city has to clear sidewalks and other small spaces. Why does he want the switch? The pay is better, he notes. Certified operators are transitioned over on a seniority basis. Drivers start accumulating overtime pay after eight hours.

DPW operations manager Laura Daniels escorts me over to the nearest maintenance facility located along W. Lincoln Ave. Despite not driving a plow, Daniels and other managers will put in plenty of hours over the weekend planning the operation, dealing with issues and communicating with the public and other city officials.

We’re greeted by fleet repair supervisor Jason Maline and his team as they’re inspecting a salt truck with its hood up. “Coolant leak,” says Maline. Another nearby vehicle is having a transmission issue. Maline’s team, one of three in the city, performs triage work during storms. Small problems get solved as quickly as possible, sometimes with an emergency trip to the hardware store, while big ones are sent to the Menomonee Valley garage after the storm.

No one would call the maintenance work glamorous, but there’s no doubt it’s important. It’s performed inside a drab facility adjacent to the south side drop off center and includes working on many aging vehicles that have visible rust. But when it’s snowing Maline’s crew is the first line of defense against breakdowns in the city’s aging fleet, which must operate around the clock. The average vehicle is over 9.5 years old.

The city is taking steps to address its plowing issues. The city will double the number of new trucks it purchases this year, part of a long-term DPW goal of having a fleet with an average age of seven years. A program was created to recruit retired drivers to be a supplemental force and five recent retirees are participating and could earn up to $39 per hour on top of their pensions.

But driver experience and employee turnover loom as issues with little in the way of solutions. The city approved a three percent raise for employees living in the city in 2019, but Daniels said workers with a Commercial Driver’s License remain in high demand and construction work is a powerful draw in the summer.

Photos

Video

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

City Hall

-

Council Blocked In Fight To Oversee Top City Officials

Dec 16th, 2025 by Jeramey Jannene

Dec 16th, 2025 by Jeramey Jannene

-

Latest Effort to Adopt New Milwaukee Flag Going Nowhere

Dec 3rd, 2025 by Jeramey Jannene

Dec 3rd, 2025 by Jeramey Jannene

-

After Deadly May Fire, Milwaukee Adds New Safety Requirements

Dec 2nd, 2025 by Jeramey Jannene

Dec 2nd, 2025 by Jeramey Jannene

Great story, Jeramey. I bookmarked it!

Great story. Funny to learn that the streets each driver selects are based on seniority, rather than skill. That likely means that the most in-experienced drivers are plowing the most challenging streets in the least reliable trucks (east side anyone?). Would love to see an incentive based on difficulty, maybe attracting more experienced drivers to the more challenging streets.

Great overview of an important task. It’s disheartening that snow removal only seems to be noticed when people decide it isn’t being taken care of fast enough.

Excellent story