The Return of Texas v. U.S.

Case could kill ACA, leave 18 million without health insurance. Which states would be hurt most?

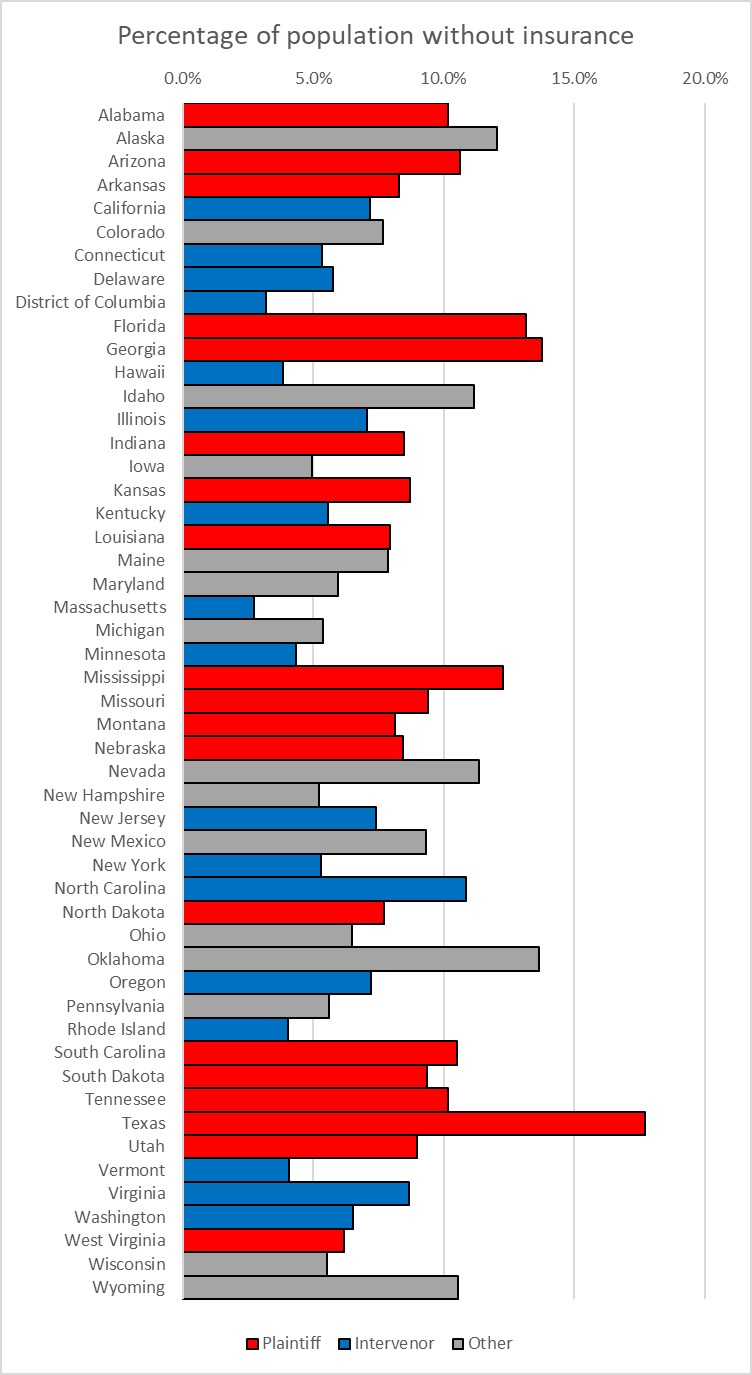

Texas v. US is the most recent of several attempts by Republican state attorney generals to get the courts to deep-six the Affordable Care Act (also called Obamacare). In the graph below, the plaintiffs — the states challenging the existence of the ACA — are shown in red. States intervening to protect the ACA are shown in blue. Those on neither side are shown in gray. Although the Trump administration is the nominal defendant, its most recent filing agreed with the plaintiffs that the ACA is unconstitutional.

In the graph, the length of the bars indicates the estimated percentage of each state’s population that lacks health insurance (from the Kaiser Family Foundation for 2018). There is a pretty strong correlation between the percentage of uninsured in a state and its willingness to join the plaintiffs opposing the ACA. On average, 10 percent of people in states pushing to end the ACA lack health insurance, compared to 5.8 percent in states supporting the coverage and 8.2 percent in states not committed to either side.

Until recently, Wisconsin would have been listed with the plaintiffs. In fact, it acted as Texas’ co-leader. Following the 2018 election, in which Attorney General Brad Schimel was defeated by Josh Kaul, the courts acceded to Kaul’s request that Wisconsin be dropped.

If successful, the lawsuit would result in a substantial increase in the number of Americans without health insurance, basically reversing the 18.6 million decline in the number of uninsured as the act took effect. In addition, a successful suit would eliminate the many other provisions of the ACA (listed here by the Kaiser Family Foundation).

The case is based on Congress’ decision in 2017 to reduce the penalty for not having health insurance — the “individual mandate” — to zero dollars. In upholding the individual mandate, Chief Justice John Roberts ruled that it was constitutional if treated as a tax. Otherwise, he argued, the government would be empowered to compel Americans into all kinds of behavior that the government thinks is beneficial for them, including, for example, compelling them to purchase broccoli.

Federal District Judge Reed O’Connor subsequently ruled that a zero tax no longer counted as a tax. Therefore, he argued, the individual mandate was unconstitutional. Thus, by pulling on this one thread, he proceeded to unravel the whole ACA.

The first step in this unraveling was to note that in 2010, when the ACA was enacted, it was widely believed that the individual mandate was needed to make the ban on discrimination against people with pre-existing conditions work. Without it, it was believed, healthy people would refuse to buy insurance, causing costs to rise.

Then O’Connor went on to assert that the ACA was designed to stand or fall as a whole. Thus, even provisions that had little connection to the individual mandate were thrown out.

O’Connor’s decision was appealed to a three-judge panel of the 5th Circuit Federal Court of Appeals. The panel, by a 2-1 vote agreed with O’Connor that reducing the individual mandate zero made it unconstitutional. However, the majority sent the case back to the district court to better explain why other parts of the act had to fall as well.

One problem with this decision is the question of standing, which requires that the person asking for a decision show a specific injury. Otherwise, anyone who does not approve of a particular policy would be free to challenge that policy in the courts.

Even weaker is the state plaintiffs’ argument that they have standing because the mandate ups their paperwork burden.

Describing the district court’s opinion as “textbook judicial overreach,” the dissenting judge says, “I would vacate the district court’s order because none of the plaintiffs have standing to challenge the coverage requirement” because complying with the mandate is purely voluntary.

She goes on:

And although I would not reach the merits or remedial issues, if I did, I would conclude that the coverage requirement is constitutional, albeit unenforceable, and entirely severable from the remainder of the Affordable Care Act. … This insight, that the coverage requirement now does nothing, should be the end of this case. Nobody has standing to challenge a law that does nothing.

This brings up a second legal issue, “severability.” When a court determines that part of a law is unconstitutional, it must decide whether other parts of the law are “severable”—can they stand on their own without the part that was overturned?

District Judge O’Connor took the maximalist position—that the whole ACA is inseverable, that every thread is connected to every other. He asserted that the individual mandate was needed for the guaranteed-issue and community-rating provisions that protect people with pre-existing conditions. But in doing so he largely ignored recent experience. As the appeals court majority points out, he “gives relatively little attention to the intent of the 2017 Congress, which appears in the analysis only as an afterthought despite the fact that the 2017 Congress had the benefit of hindsight over the 2010 Congress: it was able to observe the ACA’s actual implementation.” In short, the 2017 Congress did not end the entire ACA law, but only the individual mandate.

The district court judge went further, ruling that parts of the ACA with little or no dependence on the individual mandate are nevertheless inseverable, including requiring nutritional information by certain chain restaurants, provisions concerning healthcare fraud, and insurance-related reforms which became law years before the effective date of the individual mandate.

Texas v. US illustrates how politicized our courts are becoming. More and more, asking which president nominated a judge is a good way to predict how the court will decide. This is evident here. The district court judge who decided the whole ACA must go was nominated by George W. Bush, as was the author of the appeals court majority decision. The decision was joined by a Trump appointee. The author of the dissent was nominated by Carter.

Texas v US also illustrates judge shopping. At the time this case was filed under the leadership of Texas and Wisconsin, Reed O’Connor was the only judge based in Fort Worth and had previously ruled against the ACA. So, filing the case in that district increased the odds of the desired decision.

After detailing some of the controversies swirling about the ACA, the appeals court decision declares:

None of these policy issues are before the court. And for good reason—the courts are not institutionally equipped to address them. These issues are far better left to the other two branches of government.

Despite these protestations, the correlation between judges’ rulings and the party of the president who nominated them has been growing, as illustrated by this case. Both judges in the majority on the appeals court panel were nominated by Republican presidents, as was Judge O’Connor.

The political strategy behind this lawsuit is puzzling. Why do Republicans think that trying to take away health insurance is smart politically?

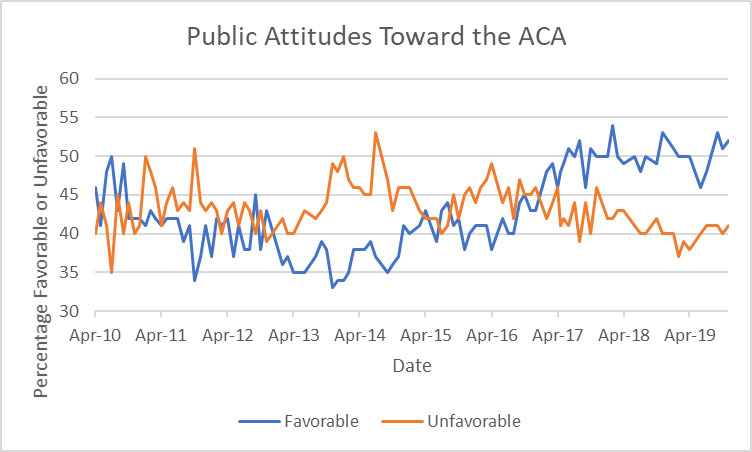

The chart below summarizes public attitudes towards the ACA based on monthly polling by the Kaiser Family Foundation. During much of the Obama administration the act was under water. That changed with the advent of the Trump administration. Donald Trump’s continual attempts to undermine or repeal the ACA have had the ironic effect in improving its popularity.

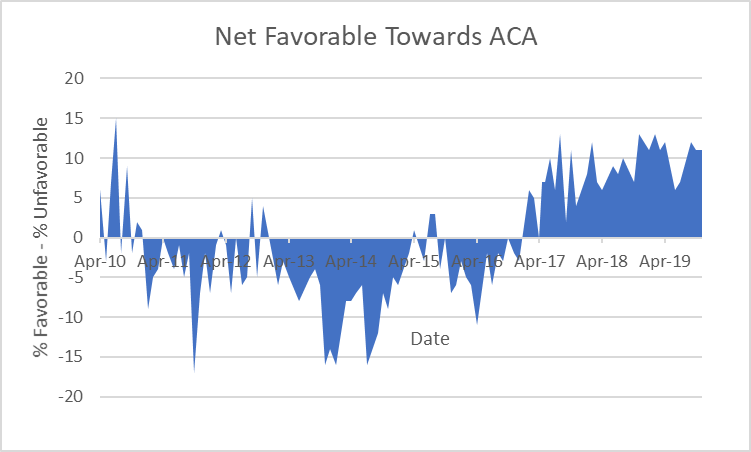

The next chart shows the ACA’s net popularity, the result of subtracting the percentage of unfavorable from the favorable. The net favorability has gone from minus 15 percent in 2015 to plus 12 percent today.

When Texas v US was first filed Wisconsin played a lead role, second only to Texas. Schimel and Wisconsin Solicitor General Misha Tseytlin were all over the case. With Kaul’s election in place of Schimel and Tony Evers in place of Scott Walker as governor, Wisconsin was dropped as a plaintiff.

It’s not likely their opposition to the ACA helped Schimel and Walker in the 2018 election. And the perception she advocated ending the ACA put Republican Leah Vukmir on the defensive during her losing race for US Senate. That underlines the political puzzle: why is threatening to increase the number of people without health insurance considered a wise move?

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

Data Wonk

-

Life Expectancy in Wisconsin vs. Other States

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Republicans Opened the Door To Redistricting

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Connection Between Life Expectancy, Poverty and Partisanship

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson