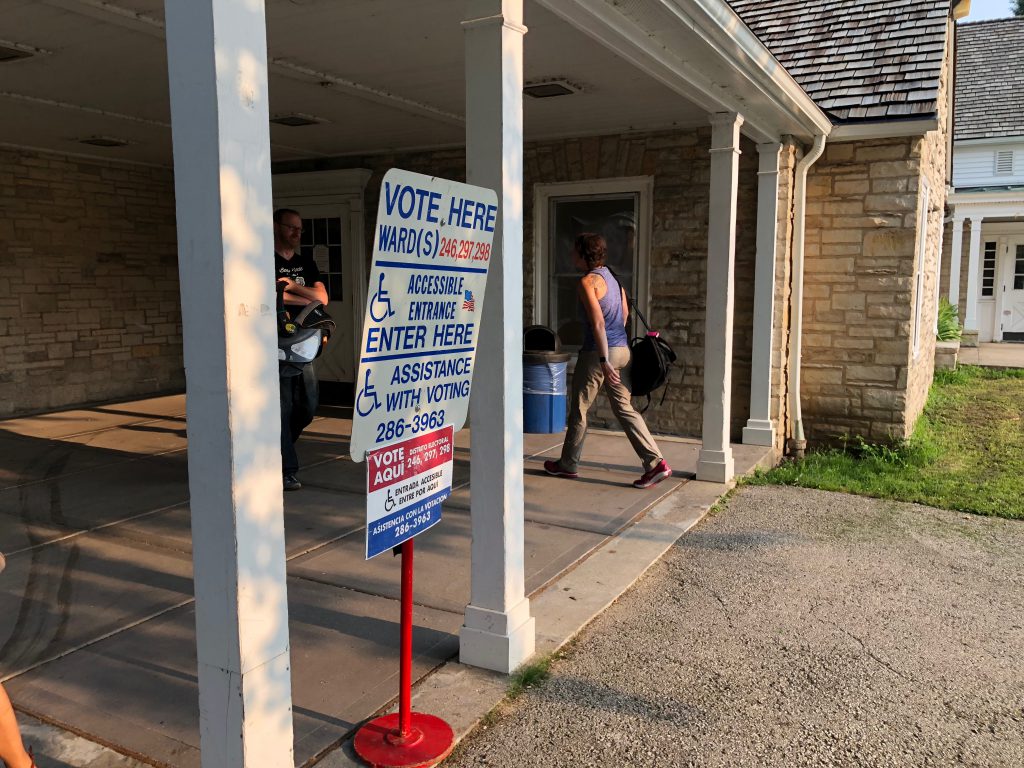

City’s Spring Turnout Up 50% Since 2017!

Contrary to early report, Milwaukee actually had strong turnout for Supreme Court race.

The 2019 Wisconsin Supreme Court election is likely to be dissected for months to come. How did candidate Brian Hagedorn pull off a win while leading conservative groups rescinded their endorsements and liberal groups outspent conservative ones?

One piece of data is clear: Hagedorn didn’t win because City of Milwaukee voters decided to stay home, as an early election story by Urban Milwaukee reported. Citywide voter turnout actually increased more than it did in the rest of Milwaukee County over the prior spring election in 2018.

In April 2018, 58,384 city residents cast a ballot, a number that grew by 17.78 percent to 68,797 in April 2019. In the other 18 municipalities that make up Milwaukee County, voter turnout only rose by only 11.79 percent (74,024 in 2018, 82,749 in 2019).

And its not the case that the city turnout was low a year ago, and had nowhere to go but up. In fact, Rebecca F. Dallet‘s successful 2018 campaign drew a strong turnout from city voters. Compared to the 2017 spring election centered around a contest between Tony Evers and Lowell Holtz for State Superintendent of Public Education, the 2018 election drew a 27.5 percent more city voters. In short, in just two years, turnout in the spring primary has grown 50.2 percent in the city. That’s pretty remarkable.

Why? Because in 2018, Milwaukee reported 248,057 registered voters, which rose to 310,634 in 2019. With the population of the city being essentially flat, where did 62,557 additional potential voters come from in one year? In large part, from a reversal of a controversial state policy.

The city reported 346,481 registered in voters in April 2017, a high point following a Presidential election. In November 2017 the state sent out 343,000 postcards to Wisconsin voters who were believed to have moved. The end result was approximately 308,000 voter registrations being dropped from the rolls in Wisconsin.

Mayor Tom Barrett and the city contested the move. “In order for this system to be put in place, you want to make sure that you are not taking people’s names off the voting rolls if they’re eligible to vote. The constitutional right to vote should be paramount here,” said Barrett in a 2018 interview with Here & Now.

The Wisconsin Elections Commission changed the practice and gave municipalities the option to reactivate some or all of those struck from the rolls. The Milwaukee Election Commission, led by executive director Neil Albrecht, decided to add all 44,000 city residents purged by the state policy back to the city’s list of registered voters. The move fixed the problem where voters could have been unsuspectingly dropped, but also deflated the city’s turnout when viewed through the percentage of registered voters casting a ballot.

Albrecht doesn’t believe the solution was perfect. “Milwaukee’s registered voter number should be more in the range of 270,000, not 310,000,” said Albrecht in an email to Urban Milwaukee. Using the 270,000 figure, the city’s turnout percentage rises to 25.5 percent of registered voters, just short of the state’s 26.6 percent turnout for eligible voters.

Albrecht sees the last election’s turnout as a success for the city. “Milwaukee has the highest rates of poverty and incarceration in the state. People in poverty are, by the nature of poverty, going to be significantly more challenged by voter registration and photo ID requirements. On any given Election Day, there are 10,000 residents in Milwaukee that are not able to vote because of their felony conviction status. Given these barriers, it is a tremendous accomplishment that Milwaukee’s voter participation is even comparable to the county’s or the state’s average,” said Albrecht in response to our story published last week. “This accomplishment is something to be celebrated, not judged or discouraged.”

And given this increase in turnout, Democrats and Republicans alike will have more motivation to explore ways to move minds in the heavily liberal city. As I reported in my 7 Numbers That Explain The Election piece, Hagedorn beat Lisa Neubauer by just under 6,000 votes, but if Neubauer had done as well as Dallet in Milwaukee (73.04 percent versus 75.36 percent of the vote) the former would have narrowed Hagedorn’s lead to only 2,000 votes.

Keep your eyes on Milwaukee. If turnout remains strong in the city the race between President Donald Trump and the Democratic challenger for this perpetual swing state and its 10 electoral votes could come down to how a few thousand Milwaukeeans vote. Don’t be surprised to see the presumptive nominee escape the downtown security perimeter at the 2020 Democratic National Convention to shake hands at Milwaukee establishments ranging from Leon’s Frozen Custard to Mr. Perkins’ Family Restaurant.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits, all detailed here.

How many eligible voters live in the City of Milwaukee? Turnout is usually based on eligible voters rather than registered voters.

Turnout in the City of Milwaukee was still significantly worse than in Dane and Waukesha counties. Even though the City of Milwaukee’s adult population is more than 40% larger than Waukesha County’s total population, it cast 40% fewer votes than Waukesha County. The City of Milwaukee’s adult population isn’t much bigger than Dane County, yet its vote total was less than 50% of Dane’s vote total.

Place Population/Adults Votes Cast

City of Milwaukee 599,086/442,282 68,770

Dane County 522,837/413,209 154,152

Waukesha County 396,731/308,790 115,424

Census Bureau, American Community Survey Estimates

City of Milwaukee, https://factfinder.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/ACS/17_5YR/DP05/1600000US5553000

Dane County,https://factfinder.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/ACS/17_5YR/DP05/0500000US55025

Waukesha County, https://factfinder.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/ACS/17_5YR/DP05/0500000US55133

I think you’re comparing apples and kumquats. The state superintendent race is nowhere near the draw that Supreme Court races have been, at least in recent years.