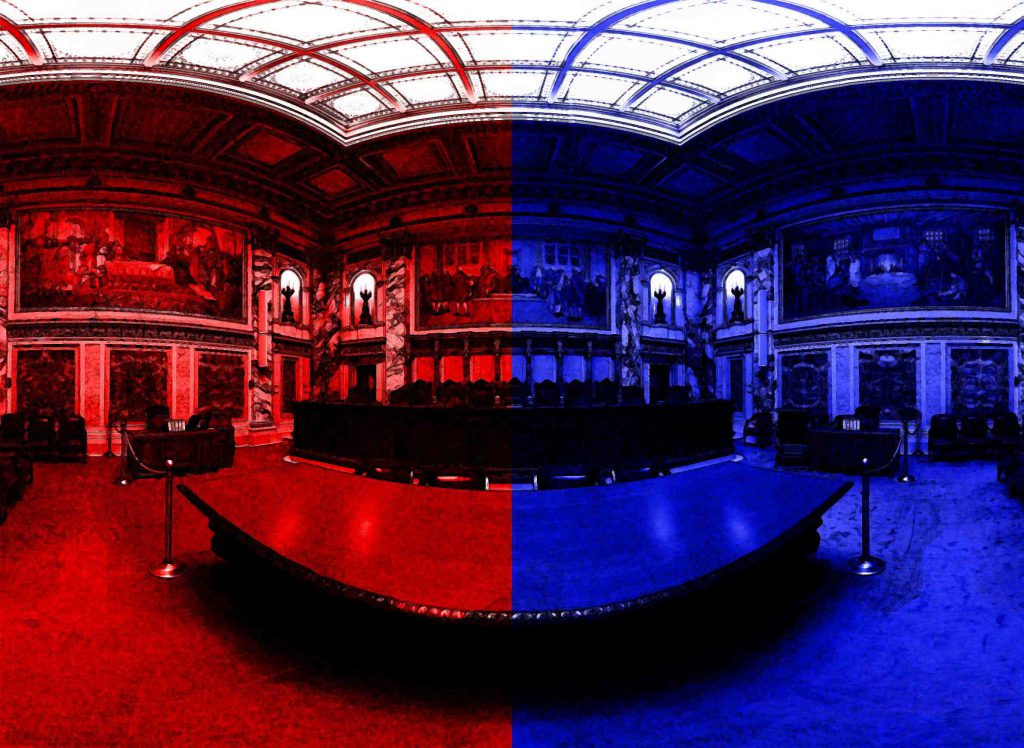

Supreme Court Vote Was Most Partisan Ever

Voting patterns in state almost exactly match the 2016 presidential victory for Trump.

When it comes to the political division between Republicans and Democrats, elections for Wisconsin Supreme Court often appear quite similar to races for the Legislature or Congress or governor or even President, even though these seats are technically non-partisan. The 2019 race between Brian Hagedorn and Lisa Neubauer was no different, and in certain ways appeared more partisan than ever given the political histories and connections of each candidate.

When voters around the state turned out on April 2 to cast their ballots, their choices confirmed this perception. Like many elections in Wisconsin in the 2010s, the outcome was extremely close, with Hagedorn claiming victory with a margin of almost 6,000 votes out of more than 1.2 million cast – a difference of less than half of one percent. Nevertheless, the voting patterns on Election Day for the state Supreme Court candidates were the most partisan in decades, surpassing even the 2018 ballot that had set a previous peak for a red versus blue divide.

Wisconsin is one of 38 states that holds elections for its state Supreme Court. The vast majority (84 percent) of those states with Supreme Court elections hold nonpartisan contests, and Wisconsin falls into this group.

It appears that partisanship is ubiquitous in today’s political landscape. But exactly how much of a role did partisanship play in the official non-partisan Wisconsin Supreme Court election between Hagedorn and Neubauer? And was partisanship more or less important in this election than in previous state Supreme Court elections?

Along with voting data, it’s informative to consider the campaign materials used by the candidates and allied groups. As was the case during the 2018 Wisconsin Supreme Court election, partisan and ideological cues frequently took center stage in campaign materials.

The Hagedorn campaign ran an ad against Neubauer that linked her to national Democratic politicians by showing images of Hillary Clinton and former U.S. Attorney General and current voting activist Eric Holder. In addition to campaign ads, partisanship and ideology are easy to identify in broader election spending patterns. For example, the Republican State Leadership Committee’s Judicial Fairness Initiative spent at least one million dollars to support Hagedorn, and the liberal Greater Wisconsin Committee and Holder’s National Democratic Redistricting Committee provided backing for Neubauer’s candidacy through advertising. (Throughout the campaign, Neubauer tried to distance herself from outside groups like this.)

Of course, it’s not just campaign materials that provide signals about a candidate’s predispositions. Voters can use the political connections Neubauer and Hagedorn have to infer their ideological and partisan leanings. For instance, Democratic Governor Jim Doyle appointed Neubauer to the Wisconsin Court of Appeals in 2007. In addition, Neubauer’s daughter is a Democratic state legislator, and her husband is a former Democratic state legislator who also chaired the Democratic Party of Wisconsin.

On the other side of the aisle, Hagedorn served as a law clerk for conservative state Supreme Court Justice Michael Gableman and as Republican Governor Scott Walker‘s chief legal counsel. Walker also appointed Hagedorn to the state appeals court in 2015.

In interviews, forums and debates, both Hagedorn and Neubauer insisted that they would be non-partisan and non-ideological as a justice on the state Supreme Court.

Turning to the electorate, county-level election results in presidential races provide a fairly good measure of the partisan leanings of a place. Examining the link between presidential and Wisconsin Supreme Court election returns, then, provides some insight into the extent to which partisanship played a role in the latter.

For the 2019 election, the relationship between Trump’s share of the two-party vote in 2016 and the share of the vote garnered by Hagedorn, the conservative candidate, can illustrate the intensity of partisan voting. Comparing these two elections, there is a strong relationship between the county-level presidential vote in 2016 and the state Supreme Court vote in 2019.

The correlation between the two measures is very high at 0.92. The maximum possible value is 1, while the minimum is 0, which would indicate no relationship between the measures. In short, partisanship clearly played an important role in Wisconsin’s 2019 Supreme Court election.

But how does the 2019 election compare to the past? Was this election more or less partisan than previous Wisconsin Supreme Court elections?

To help put 2019 in context, county-level data on the correlation between presidential and state Supreme Court election results going back to 1996 answer these questions. The correlations for the court races are .03 in 1996, .59 in 1997, .47 in 1999, .66 in 2000, .19 in 2003, .77 in 2007, .74 in 2008, .78 in 2009, .88 in 2011, .81 in 2013, .87 in 2016 and .89 in 2018, each based on the preceding presidential election. In other words, partisanship in state Supreme Court voting has generally increased for over a decade.

Given the correlation of 0.92 for 2019, it appears that the election between Hagedorn and Neubauer was even more partisan than the 2018 election. That race, between conservative candidate Michael Screnock and liberal candidate Rebecca Dallet was itself the most partisan Wisconsin Supreme Court election over the same time frame.

Indeed, support for Hagedorn is highly correlated with support for Screnock. The correlation between Hagedorn’s share of the vote in 2019 and Screnock’s share of the vote in 2018 is 0.95. In short, Hagedorn tended to do well in places where Screnock did well a year before. The difference in the outcome of the two elections, on the other hand, is related to differing levels of turnout around the state

Overall, this pattern is likely to agitate those who think that non-partisan elections are (or should be) non-partisan. They are clearly not free of partisanship. Even when some partisan cues are absent in an election, partisanship structures the vote.

However, there are a range of possible ways to accept or address this state of affairs.

Wisconsinites could simply acknowledge that partisanship now seeps into officially non-partisan races and keep things as they are.

Alternatively, the state could switch from non-partisan to partisan elections. Research has indicated that partisan judicial elections see higher turnout rates than non-partisan contests.

Another idea would be to stop electing state Supreme Court justices all together. While many states hold elections for judges, there are certainly other institutional arrangements. Some states, for instance, use merit selection. The basic idea under a merit system is that a nominating commission reviews candidate qualifications and then provides a list of acceptable individuals to the state’s governor, who appoints a judge based on the list of recommendations. After a judge serves an initial term, voters decide in a retention election whether the person should continue serving.

Changing political institutions is notoriously difficult, though. Therefore, it is unlikely Wisconsin would change its judicial selection process unless people mobilize around this issue and bring it to the attention of policymakers. For the time being, and as long as deep political polarization continues, Wisconsin is likely continue to see incredibly partisan non-partisan elections.

Aaron Weinschenk is a an associate professor of political science at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay.

Wisconsin’s 2019 Supreme Court Voters Hit New Peak Of Partisanship was originally published on WisContext which produced the article in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio and Wisconsin Public Television.